“The loot we pillaged had been plundered.” It’s one of the most indelible lines from Jeremy Atherton Lin’s Gay Bar. An aphorism that speaks to how gay men stealing women’s “act” had eventually come back full-circle in terms of women subsequently imitating gay men who had been imitating them. Making for some kind of hyper-meta-parody. To this end, Madonna has been imitating gay men for some time, herself once noting that she’s a gay man trapped in a woman’s body. That said, it didn’t take a die-hard Madonna fan to pinpoint that what Beyoncé was doing with “Break My Soul” and Renaissance already happened in the early 90s with both “Vogue” as a single and Erotica as an album. Except that when Beyoncé does it, it can be viewed as “taking back” house music for Black people. As though the majority of house music wasn’t already attributed to musicians like Crystal Waters, C+C Music Factory, La Bouche, Corona and Robin S. So no, let us not be duped into thinking Bey is some kind of beneficent soul “restoring” music rightfully to “her people” (since she so enjoys treating the Black community as her royal subjects). It’s never been a secret that house music is Black people. And yes, Madonna was absolutely paramount to bringing that sound to the Midwest with her mainstream reach.

That was always the mark of Madonna’s business acumen: take an underground sound, adopt as it her own and make it palatable to the masses milling around the proverbial Mall of America. That’s what “Vogue” was on every level. Saturating the hoi polloi with Black gay culture as they had never known. It’s what New York would like to call “bringing New York to the shitkickers.” And oh, how Madonna did in that spring and summer of 1990, when “Vogue” was the only thing breathing life into a repressed America run by conservative old white men. Beyoncé would have been eight at the time of the release, in addition to the May dates when Madonna showed up to Houston for the Blond Ambition Tour (apparently, M mistakenly saluted the Dallas crowd with a Houston greeting as well—Texas is all the same, innit?). But perhaps Beyoncé was “too fucking busy” to pay much attention to the Queen of Pop’s controversy stirrings as she had decided already at a talent show—after singing another prime example of “white people shit” (John Lennon’s “Imagine”)—to pursue singing seriously. Like Britney Spears, she was groomed early on for this type of career (maybe that’s why Bey proclaims on her “The Queens Remix” of “Break My Soul,” “I’m built for this/I can take it”), and both artists were signed to labels by the late 90s.

This trajectory is in direct contrast to how Madonna came up in the world of fame, forging a path entirely her own. One that took years of ups, downs, false starts and broke assery as she continued to fear getting “too old” to be famous. And, by industry standards even then, she was “pushing it” at twenty-four, when she finally released her first single, “Everybody.” An unconventional debut in every way, it was certainly not what the average music executive would call “radio-friendly” for the time. Nonetheless, it established the trend in Madonna’s career of taking what was happening in the sweaty, underground clubs of major cities and bringing it to the unversed rabble. Time and time again, this would be her modus operandi. As though Madonna’s true destiny in becoming famous was to channel her erstwhile perspective as an “outsider Midwesterner” and make sure that no other Midwesterner who didn’t opt to move to New York ever felt that way thanks to her music.

As for “Everybody,” it would also establish the precedent in Madonna’s career of being “linked to Black folk.” For, as the story goes, “Sire Records marketed the soulful nature of the dance song for the black audience and Madonna was promoted as an African-American artist, thereby fitting the record into a radio playlist where the song might chart. In New York, the song was played on 92 KTU which had an African-American audience.” The cover art for the single was strategically missing Madonna’s presence for this very reason as well. Instead featuring a “hip hop collage of downtown New York” by Lou Beach, Madonna’s comfortableness with this rather deliberate cultivation of “omission” at the outset also played into her open admission to Arsenio Hall (in 1990, the Year of “Vogue”) that she wanted to “be Black” because “all my girlfriends were Black. And it seemed that their parents were more lenient than my parents and somehow I had it stuck in my mind that it was because they were Black they had more fun.”

As if that weren’t a cringe-y enough statement, Madonna continued by saying that her Black friends could “dance their asses off, too, so I got a few lessons in their garage—dance lessons… I was incredibly jealous of all my Black girlfriends because they could have braids in their hair that stuck up everywhere. So I would go through this incredible ordeal of putting wire in my hair and braiding it so that I could make my hair stick up. I used to make cornrows and everything.” In short, she was rehashing the beginnings of her appropriative tendencies (also cropping up with more cornrows in the “Human Nature” video).

To conclude the very Get Out sentiments expressed, Madonna said, “If being Black is synonymous with having a soul, then yes, I feel that I am.” And Madonna clearly broke Bey’s soul to get so blatantly “paid homage to” for Renaissance. Yet one can’t pay homage to Madonna’s “Vogue” era without understanding that it was already plundered from others in the first place. Many of whom (like Jose and Luis Xtravaganza) were willing to go along with the exploitation because, well, who wouldn’t go for an opportunity to get more money and exposure even if it meant Madonna getting all the glory (and most of the money)? And yet, what about those who, unlike Jose and Luis, did not get their piece of the pie for a dance craze and attitude that originated from the ballroom “subculture”?

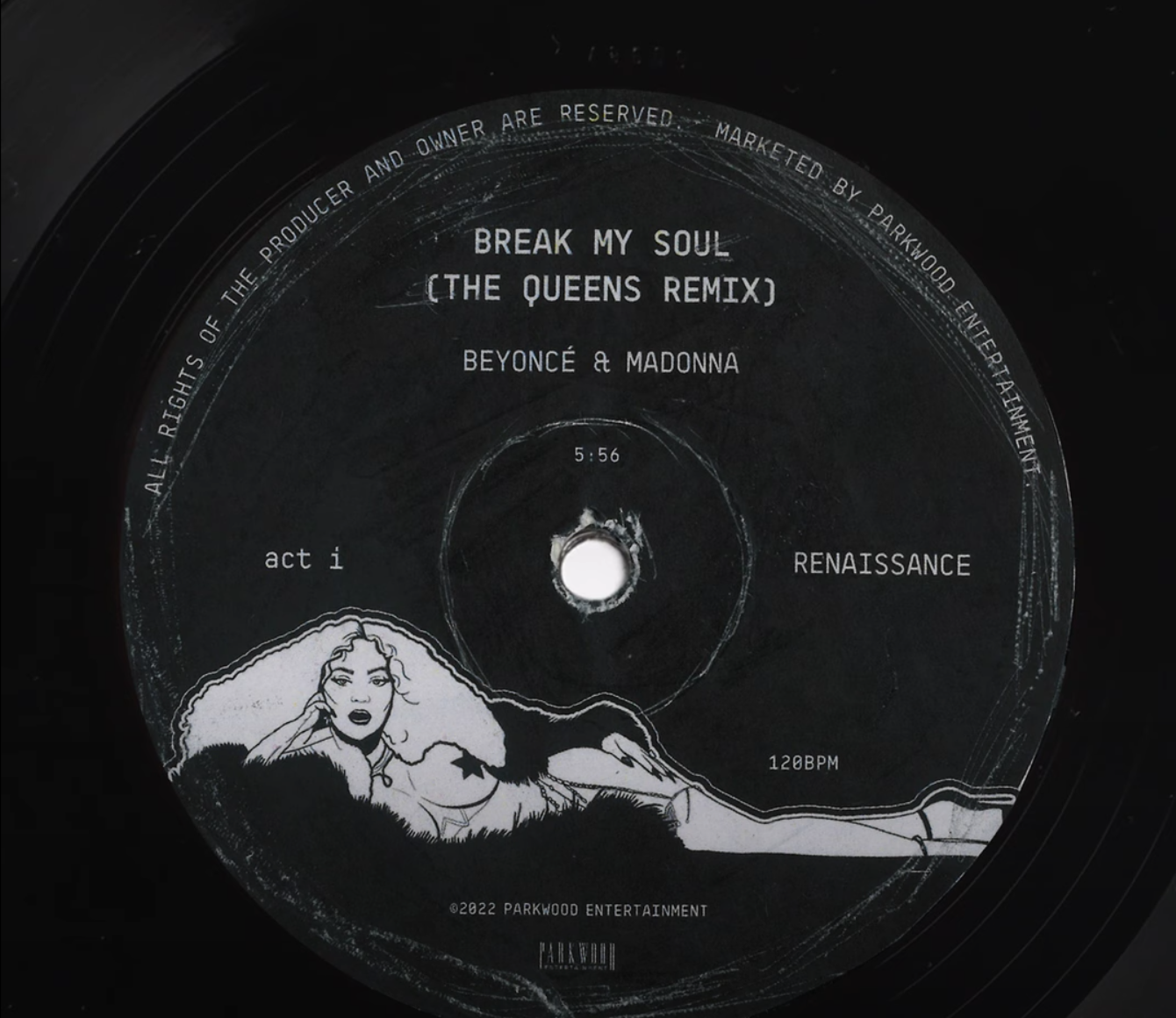

While “voguing” came and went, viewed as just another one of “Madonna’s phases,” those in the ballroom scene would remain forever committed. Still facing financial and discriminatory struggles while M not only profited from their culture, but also summarily “erased” them as the true creators of the art. These are the people Beyoncé claims to want to raise up with her own “superior” voice. Somewhat ironic, then, to collaborate with the very person who many insist took it from them. Which is part of why on “The Queens Remix” of “Break My Soul,” Yoncé amends the Madonna “rap” featuring the names of all-white legends of Old Hollywood with her own coterie of Black legends of the music industry. The result is a much lengthier list that includes, “Rosetta Tharpe, Santigold, Bessie Smith, Nina Simone, Betty Davis, Solange Knowles, Badu, Lizzo, Kelly Rowl’, Lauryn Hill, Roberta Flack, Toni, Janet, Tierra Whack, Missy, Diana, Grace Jones, Aretha, Anita, Grace Jones, Helen Folasade Adu, Jilly from Philly, I love you, boo.” She later adds (in part to honor all of Destiny’s Child), “Michelle, Chlöe, Halle, Aaliyah, Alicia, Whitney, RiRi, Nicki.” Naturally, bell hooks wouldn’t be on the list, what with her all-too-real assessments of both M and Bey as exploitative capitalist queens.

Which takes us back to hooks’ illustrious essay on Madonna that commences, “Once I read in an interview with Madonna where she talked about her envy of black culture, where she stated that she wanted to be black as a child. It is a sign of white privilege to be able to ‘see’ blackness and black culture from a standpoint where only the rich culture of opposition black people have created in resistance marks and defines us…” But that is the crux of what Madonna has done throughout her decades in “the business.” And make no mistake, pillaging is a business. A very lucrative one, at that. Thus, hooks also noting, “And it is no wonder then that when [white folks] attempt to imitate the joy in living which they see as the ‘essence’ of soul and blackness, their cultural productions may have an air of sham and falseness that may titillate and even move white audiences yet leave many black folks cold…” Especially Black women, hooks was sure to emphasize. But Madonna isn’t leaving Beyoncé cold at all. Instead, she’s leaving her very heated (the song title on Renaissance that found Bey using “spaz”). Enough to fan herself with all the additional bills she’s making from repurposing this song. Because, like Madonna, “Beyoncé’s audience is the world, and that world of business and money-making has no color.” That’s what hooks’ appraisal was of “Queen” Bey. A woman who, for Madonna, is also very useful. For “…she must always position herself as an outsider in relation to black culture. It is that position of outsider that enables her to colonize and appropriate black experience for her own opportunistic ends even as she attempts to mask her acts of racist aggression as affirmation. And no other group sees that as clearly as black females in this society.” Even Beyoncé must see it. Though perhaps she simply doesn’t care that “Madonna never articulates the cultural debt she owes black females.”

In contrast, that’s all Beyoncé seems to do (almost to make up for how much she’s had to remain in the back pocket of her white audience for too long). Yet her verbal reverence so often feels negated by some of her actions. Including this recent decision to overtly emulate Madonna’s plundered 90s swag. A Twitter account called @ProfBlackTruth is among the few that would dare to speak out against it by noting, “Beyoncé is paying homage to Madonna. A racist who uses black children as her servants and mentally torments them for her own sick amusement. This is who the white media wants black women to model themselves after.” And yes, that last statement is definitely true, with colorism being the new accepted form of racism. Some, of course, might think that “black children as her servants” comment is way harsh, Tai, but it does harken back to something Azealia Banks (who has also come for Beyoncé plenty of times) said about Madonna’s “caring skills” for her adopted twins when she commented on one of M’s posts, “Omg please nurture their hair!!! This is an important time for character development. Don’t masculinize them and make them have boy hair styles because you’re too lazy to have any original thoughts about your children’s hair. Don’t adopt black girls just to post them on Instagram, actually show a real care for these future black women and make their hair as nice as the kitchen Tf. And Madonna has too much money for there not to be even a DROP of castor oil on these girls’ heads before she decided to post her refugee children dancing in her fancy kitchen to show how cultured she is as a rich top one-percent white celebrity.”

This outrage on Banks’ part speaks to the harm that can still exist within what can be viewed as objectively “good” acts. As hooks phrases it, “It’s possible to hire gay people, support AIDS projects and still be biased in the direction of phallic patriarchal heterosexuality.” Something Beyoncé is well-versed in too, except without the Madonna-level consistency of supporting the LGBTQIA+ community (seeming only to do so when it suits Bey’s mood). hooks goes on to say that, “In Truth or Dare Madonna clearly revealed that she can only think of exerting power along very traditional, white supremacist, capitalistic, patriarchal lines.”

Ones that she seeks to blur by offering up “Vogue” for Beyoncé’s taking as though to somehow “give back” (or at least share) what she once so overtly took. But it only proves that Madonna is still working within those “very traditional, white supremacist, capitalistic, patriarchal lines” by cooperating with a person who herself operates within that framework. Regardless of being a supposed archetype of Black Excellence. Though, evidently, she wasn’t excellent enough to inform Kelis about sampling her. But clearly, “Queen Mother” Madonna was worth consulting about using “Vogue,” with the remix artwork announcing, “All rights of the producer and owner are reserved.”

The remix is also another instance of Beyoncé persisting in coming up with lines that aim to deflect blame or criticism of any kind (e.g., “Love thy hater” and “Redirect all that anger/Give it to me”). Built-in legal jargon, of sorts, that makes one think she might not be totally blissfully unaware that she has effectively found herself in bed with the quintessential “enemy” of Black culture. That is, in terms of bastardizing and commodifying it for her own white lady gains.

All of this isn’t to say that Beyoncé and Madonna are not talented cultural tour de forces. But it is important to call out that the cycle of capitalizing on queer Black communities in an exploitative manner is repeating with this collaboration, whether you see people “happily” dancing to it or not. And, as hooks said, “Sometimes it is difficult to find words to make a critique when we find ourselves attracted by some aspect of a performer’s act and disturbed by others, or when a performer shows more interest in promoting progressive social causes than is customary. We may see that performer as above critique. Or we may feel our critique will in no way intervene on the worship of them as a cultural icon. To say nothing, however, is to be complicit…”