As Todd Haynes’ debut 1991 film boldly dared to explore the work of Jean Genet in a manner that no one had attempted to take on before, it also managed to bring life to a genre not yet fully established in the film industry: Queer Cinema. Strung together through the lens of three different narratives, all inspired by the works of Genet, Haynes makes a remarkable statement on how those of a “different” sexuality are relegated to the role of pariah–or in some cases, even monster.

The line, “The whole world is dying of panicky fright,” taken from Genet’s Crimes of Passion, opens the film, and gives us immediate insight into the notion that those who live in fear of others do so merely because they are not like them. Case in point is the first story, told through TV tabloid-like means with a narrator rehashing how a seven-year-old named Richie shot his father in their Long Island home and subsequently flew out the window, according to his mother. Setting the tone for the fantastical and surreal, the narrator asks, “What really happened to Richie Beacon?” This segues into the hands of a child fumbling through his parents’ dresser to steal anything of value (all of Genet’s characters tend to have sticky fingers).

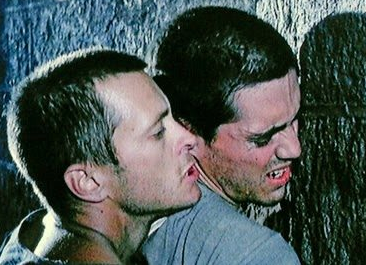

This leads into the life of the child as a man, John Broom (Scott Renderer), a contented prisoner who declares, “In submitting to prison life, in embracing it, I could reject the world that had rejected me.” During his time in a juvenile detention center, he encountered another prisoner named Jack Bolton (James Lyons) who was sexually humiliated by all the others. His attraction to Jack returns later on when he sees him once again as an adult (it’s sort of like Moonlight that way). With each new segment dividing itself with the presence of another quote, our introduction to Dr. Thomas Graves (Larry Maxwell) is commenced with: “A child is born and he is given a name. Suddenly, he can see himself. He recognizes his position in the world. For many, this experience, like that of being born, is one of horror.”

From here, we learn of Dr. Graves’ intent desire to capture the human sex drive as part of his research. His colleagues, however, call into question his competence, forcing him to go into an even more depraved research mode as Dr. Nancy Olsen (Susan Gayle Norman) enters the picture from Boston to help him and express her admiration for his work. Distracted by her, shall we say, measurements as she walks away, Graves accidentally drinks from the wrong glass, consuming the contents of his research so that he ends up transforming into a murderous leper with a strong sexual appetite.

From here, Haynes cuts back to the tabloid tale of Richie Beacon, using neighbors’ accounts of the murder to heighten the sense of cartoonish drama. We’re then led again to John Broom’s story, as he recounts how his notoriety for thieving made him an undesirable in any foster home. And so this interweaving continues throughout the film, with each character coming to no good end, especially not Dr. Graves.

What it all boils down to is that “Love comes slyly, like a thief.” And, regardless of the protagonists’ sexuality, it seems that in every case, love (or maybe in Richie’s case, lack of love) was their undoing–the thing that drove them to madness. But as Genet sagely put it, “A man must dream a long time in order to act with grandeur, and dreaming is nursed in darkness.” So concludes Haynes’ evermore retrospectively brilliant debut, which seems such a long way now from the lushness of Velvet Goldmine or Carol, yet somehow still a natural trajectory. Because, ultimately, all of Haynes’ work explores forbidden yearning and unrealized potential.