When a story has the kind of impact that Frankenstein did—and then enters the public domain—the oversaturation of that narrative can automatically offput an audience. This definitely wasn’t the case with Alasdair Gray’s award-winning 1992 novel, Poor Things. As with his previous works, Lanark and 1982, Janine, Glasgow is as much a “character” as anyone else. And, in truth, part of the reason Gray seemed willing to let Yorgos Lanthimos, de facto Tony McNamara (who also wrote the script for Lanthimos’ The Favourite and co-wrote Craig Gillespie’s Cruella [also starring Stone]), adapt the book was his assumption that Glasgow would remain the backdrop (indeed, Gray gave Lanthimos a walking tour of the city when he came to visit him to discuss adapting the book). Or at least not get eradicated completely.

For, from the outset of Gray’s career, he established himself not just as a “Scottish writer,” but as a Glaswegian. It was in his debut, Lanark, that he asserted as much with lines like, “Glasgow is a magnificent city… Why do we hardly ever notice that?” The response? “Because nobody imagines living here… think of Florence, Paris, London, New York. Nobody visiting them for the first time is a stranger because he’s already visited them in paintings, novels, history books and films. But if a city hasn’t been used by an artist not even the inhabitants live there imaginatively.” Thus, there’s no denying it would have been important for Gray to see Glasgow come to life on the screen for Poor Things. Instead, Lanthimos opted for London—the ultimate slap in the face for Scots—as the primary geographical anchor of the tale. And by removing Glasgow from the narrative entirely (while still giving Godwin [Willem Dafoe] a botched Scottish accent), Lanthimos effectively plays up what Mark Renton (eventually portrayed by Ewan McGregor) said in Trainspotting, “It’s shite being Scottish! We’re the lowest of the low. The scum of the fucking Earth! The most wretched, miserable, servile, pathetic trash that was ever shat into civilization. Some hate the English. I don’t. They’re just wankers. We, on the other hand, are colonized by wankers. Can’t even find a decent culture to be colonized by. We’re ruled by effete arseholes. It’s a shite state of affairs to be in, Tommy, and all the fresh air in the world won’t make any fucking difference!”

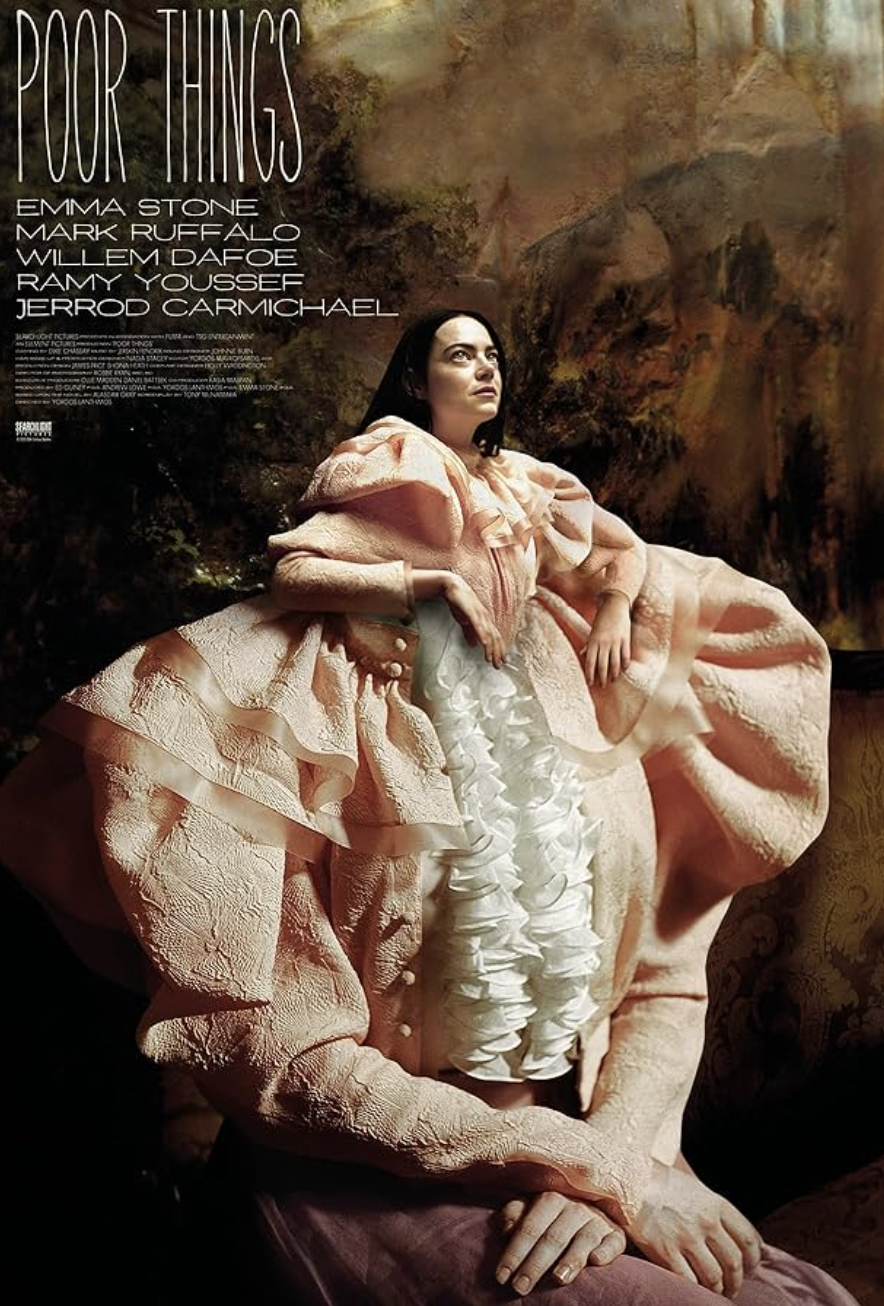

It did to Gray, though. Who felt that wielding Glasgow in his novels would give it the exposure it so richly deserved. This being a major influence on the likes of subsequent Scottish writers such as the alluded-to-above Irvine Welsh. However, for those able to get past the total removal of Glasgow from a work that made it a central aspect, Lanthimos’ Poor Things is an important meditation on not only what it means to have agency, but what it means to have it as a woman. A gender that, granted, has made political gains since the era during which Bella Baxter (Emma Stone) is forced to live in, but one that also remains tragically subjugated in ways that few white men could ever understand. White men like Godwin and his assistant in the “experiment,” Max McCandles (Ramy Youssef). The former is the proverbial Dr. Frankenstein of the story, and Bella (formerly Victoria Blessington) his unlikely and unwitting “creation.” Created, in fact, from the “raw material” of a suicide case. One that we see take place in the first scene of the movie, with the back of Victoria’s head facing us just before she plummets to her death from a high-up bridge. Fortunately (or unfortunately), Victoria’s loss of life is Bella Baxter’s gain. Not to mention Godwin’s (who Bella refers to unironically as “God”). After all, it’s not every day that the ideal scientific experiment falls (literally) into one’s lap.

Re-outfitting her head with a new brain (namely, that of the unborn baby inside of her—a little far-fetched, sure, but worth suspension of disbelief for the symbolic cachet of what that means), Godwin enlists Max to help document her progress and development. Both of which accelerate at a rate far more rapid than either one of them expects. It is Bella’s “precociousness” for her “age,” so to speak, that leads Godwin to become more emotionally attached to her than he would like to as a “man of science.” One who must stick with cold, hard reason rather than emotionalism when it comes to this experiment. The “experiment” (a.k.a. woman) he does his best to keep in controlled conditions—the same way most men for the bulk of humanity’s existence on Earth have. And the same way most men have failed. For to try to “rein in” a woman is about as effective as trying to stick a round peg in a square hole…quite simply, it doesn’t compute.

Least of all for someone as inherently curious and full of enthusiasm for life as Bella. Whose unawareness of what her looks “mean” for her only adds to the absurdity of her “uncouthness” (by polite society’s standards). Regarding her physical attractiveness, Max says something to the effect of “what a beautiful retard” she is (the only way a character can utter such a thing these days, of course, is if the time period is far enough back in the past). But there is nothing “retarded” about Bella, so much as the repressed world she inhabits. To be sure, Victorian-era England was one of many heights of societal repression in human history, especially with regard to sexuality. More to the point, female sexuality. But the instant that Bella discovers, with the help of a hard piece of fruit, that she can get pleasure “down there,” she wonders why people don’t do “furious jumping” all the time. To her, it’s utter madness to deny oneself that type of ecstasy. Far more mad than letting loose one’s inhibitions and hang-ups in order to secure their pleasure, therefore their best life.

Continuing to attempt controlling her by ensuring she never leaves the house, Godwin suggests that Max marries Bella. To assist with drawing up a very detailed marriage contract is Duncan Wedderburn (Mark Ruffalo), who is so intrigued by the subject inspiring such a rigid need for control that he seeks her out in the house and ends up casually fingering her. Which, of course, she doesn’t mind (prior to this, she had already been begging Max to “touch each other’s genitals”). But he refuses to do so until they’re married. Duncan, on the other hand, has no such Victorian scruples, and expresses his desire to take Bella away from her oppression. To see the world and go on adventures that will satisfy her hunger for such outings.

Himself a “libertine,” Duncan makes the false assumption that he can “handle” a woman like Bella. Once they arrive in Lisbon, however, he finds that even he can’t keep up with her “appetites,” both gustatorial and sexual (at one point, she asks Duncan why people don’t just “furiously jump” all the time). She is a woman who wants to, essentially, “eat” the world. Gobble it up in huge bites so that she might experience and absorb it all. That kind of passion and freedom is something that has long been terrifying to men…in addition to women who have sex for money. Which, of course, is the path Bella ends up going down (ergo, the Frankenhooker correlation), for it combines her love of sex with her need of money. When Duncan keeps pursuing her even after finding out that she whored herself to get them food and lodging for the night, he berates her for being a strumpet. She shouts back, “We are the means of our own production!” Socialism was always part of the underlying message in Gray’s novels, and McNamara is sure to incorporate it here. In addition to the idea that sex work is one of the most long-standing methods by which a woman has secured, for better or worse, her own financial independence (even when forced to give an undeserved cut to her pimp).

Her “prostitute period” (Bella does, indeed, live so many lives) occurs after Duncan tries to “contain” her on a cruise ship (effectively kidnapping her to do so). Though he is convinced this will allow him to keep her all to himself (“ownership” being one of the most important things to men), Bella is quick to befriend an older woman named Martha Von Kurtzroc (Hanna Schygulla) and her platonic consort, Harry Astley (Jerrod Carmicahel). Harry is immediately described by Martha as a “cynic.” One who tries to warn Bella that the world isn’t all orgasms and oysters. When she insists she’s ready to see the world for what it “really” is, Harry accompanies her on one of the ship’s stops into Alexandria, where the atrocities below them do not align with the life of luxury they’re living above (this scene being a prime example of the fantastical set designs that recall Michel Gondry’s Mood Indigo, also based on a novel…in that instance, Boris Vian’s Froth on the Daydream). Alas, it is when Bella is forced to recognize the pain and horror of the world, thanks to Harry’s own brand of cruelty, that she does further develop her brain to a point that makes her more “human” than ever. Not just because she’s on the road to becoming more desensitized and apathetic, but because she’s finally comprehending that the appreciation of the “good” in life (this inferring decadence, for some) also means experiencing and acknowledging the “bad.” The horrific.

As Emma Stone put it in her acceptance speech for Best Actress at the 2024 Golden Globes, “I see this as a rom-com. But in the sense of, uh, Bella falls in love with life itself, rather than a person. And she accepts the good and the bad in equal measure… All of it counts and all of it is important.” Sometimes, it takes an entirely new brain to re-approach life with that kind of perspective. And most times, it takes an entirely new brain for men not to be such oppressive prickheads.