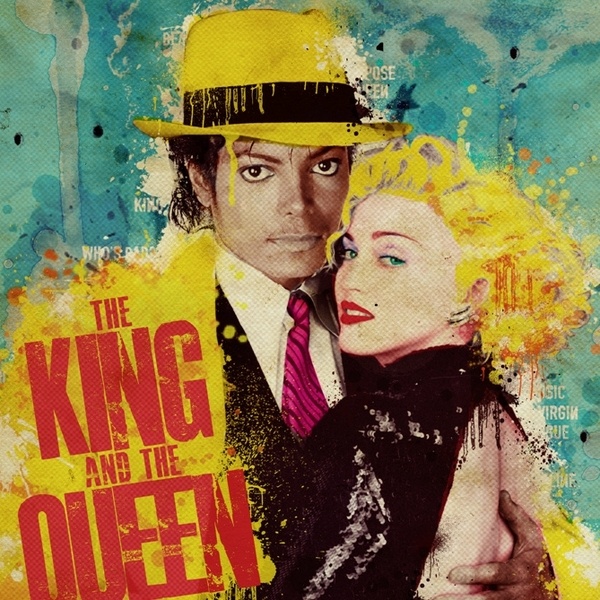

As the internet has served as a conduit for what once would have been called “niches” to thrive, the phenomenon of “monoculture” has been essentially eradicated as we find ourselves roughly twenty years into the twenty-first century. A recent statement from Grimes pulled from an interview with Lana Del Rey in which both sounded like NYU students waxing poetic in their SoHo “dorm” cut to the quick of why there seems to be so little unity among the masses anymore (least of all generationally)–try as one might to pin it solely on the shoulders of Trump. For one of the most succinct attempts at profundity Grimes made was this: “We entered this monoculture zone [in the twentieth century] where everything got more centered into single sources of power. Everyone was in agreement on who the biggest stars in the world were. Everybody knew Michael Jackson and Madonna. But now, with the internet and all of these different forms of media, we’re entering a new period of customization again where people are able to customize their existence more.”

A “customized” existence, however, doesn’t necessarily ensure a better one than when mass media was providing us with fewer choices to be shoved down our throats. If anything, the plethora of choice without much in the way of quality control has been a contributing factor to the waning attention span of your average earthling. Not to mention his or her increasing lack of identification with the rest of humanity, for each person is now able to seek out the most esoteric of entertainment sources to ephemerally fill the void inside. Under the assumption that modern pop culture was more or less born in the 1980s (when MTV was), the steady increase of “options”–whether musically or filmically–over time only augmented in the 90s as cable TV catered to interests and age groups of varying kinds. Channels like HBO and Nickelodeon continued to demand new content to feed its voracious viewers. And networks like these were themselves another onset of creating a layer of classist division (for one had to pay a considerable amount of extra money per month to get them) the way certain streaming services later would as well. Of course, in the world of cinema, diversification had already started long ago, with the breakdown of the studio system model in the 60s. “Indie” movies in a purer sense of the word–that is to say, independently financed–meant that formerly assured “blockbusters” weren’t guaranteed to have the same cachet with audiences anymore. This is the moment in time when one can pinpoint the demise of a pop culturally united front. For no, not everyone was going to see Carnival of Souls or Faces. You had to be a specific sort of person.

And with the acknowledgement that content in media needed to be driven toward pleasing different walks of life came the acknowledgement that the previous “enforcement” of unity within nations was ersatz, disingenuous. This is part of the reason why the 50s seem so cartoonish and phony in retrospect. Sure, all of the country was watching I Love Lucy and Leave It to Beaver, but these monocultural entities were merely a means for the McCarthy-dominated government to indoctrinate the people with their message. In fact, if demagogues like Trump were truly shrewd, they would come up with a way to cut the available content online and elsewhere in half. Alas, that would take ample amounts of money and power… again, one wonders why Trump hasn’t tried to do it. It’s the quickest way to effectively brainwash. To make a nation believe in a common enemy or cause.

Alas, with the advent of MySpace in 2003 and the music it allowed aspirants to post, internet users were provided with something once previously arcane. The landslide of endless choice in all facets of pop culture was begat from this twenty-first century innovation. The democratization of art that made potential fame therefore recognition plausible for a vastly higher percentage of people opened a floodgate from whence there was no turning back (which makes one think that sometime in the not so distant future, there will be an inverse aphorism to Andy Warhol’s in the form of: “In the future everyone will be anonymous for fifteen minutes.”). What’s more, now there was even less money to be made in the arts as the attentions of listeners and viewers were so extensively stretched to keep up with everything.

While many are understandably pleased with the decentralization of monoculture that made people like Madonna and Michael Jackson so ultra-famous, there is a certain bittersweetness to the now defunct idea that one of the few common grounds people could share was having seen or listened to the same things and being able to comment on and critique them together. In the present, it’s getting harder and harder to relate to one’s fellow humans unless you’re about that depressing and nonpareil entity called a Reddit thread. But then, those people aren’t even tangible. And that was the truly great thing about monoculture–no matter who you encountered in real life, they had some sense of what the fuck you were talking about.