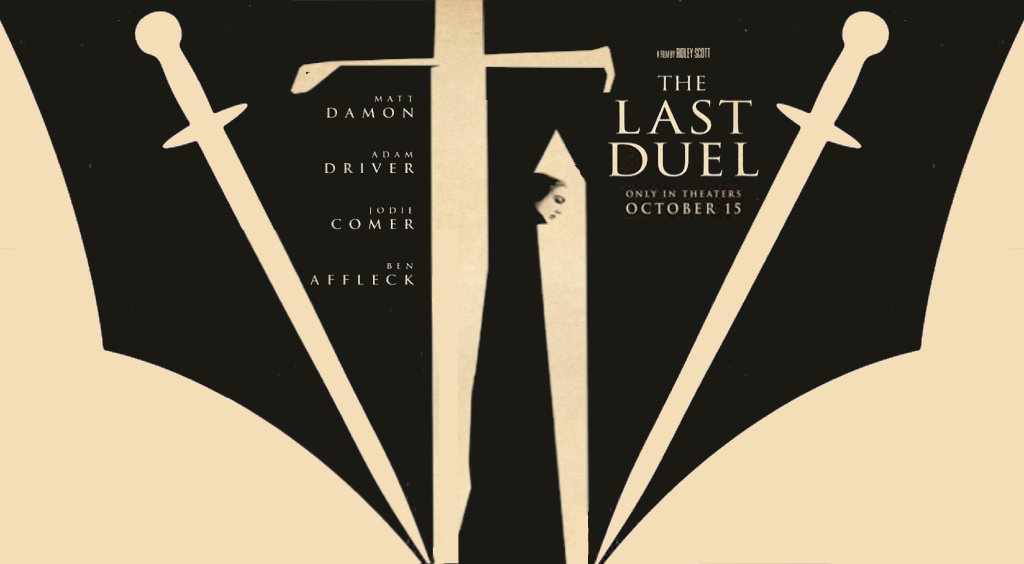

Told from three separate perspectives, Ridley Scott begins his epic narrative, The Last Duel on 29 December 1386—apparently, it takes going that far back in history to make things seem interesting or novel again. For House of Gucci’s “period piece” attempts in the 70s and 80s are actually better left to Ryan Murphy’s Halston. Thus, let us not discount the fact that Scott simply had a better screenplay to work with for this film than what Becky Johnston and Roberto Bentivegna provided for House of Gucci. There’s no denying that a large part of that was thanks to co-screenwriter Nicole Holofcener (and yeah, maybe Ben Affleck and Matt Damon helped too), who still has no issue with citing Woody Allen as a major influence on her style and career. After all, she spent her youth on the sets of Allen’s films thanks to her stepfather being producer Charles H. Joffe before becoming a production assistant on A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy, among other crew-related roles that were to come on Allen’s films. With that sort of influence, it’s no wonder that Holofcener’s work has always possessed the same “indie” spirit as Allen’s movies, in addition to their focus on, let’s just say it, affluent white people problems.

One could even argue that The Last Duel is sort of an apex of affluent white people problems for the medieval era, save for the horrifying part where Marguerite de Carrouges (Jodie Comer, in a big departure from Free Guy), the wife of a Norman soldier and, later, knight named Jean de Carrouges (Matt Damon), is just one of many women viewed as nothing more than male property. Thus, her rape by another knight—formerly but a squire to Count Pierre II of Alençon (Ben Affleck)—named Jacques Le Gris (Adam Driver) has nothing to do with the affront to her body or psyche, so much as the fact that she is the “property” of Jean’s that has been “pilfered,” violated. Jean’s willingness to “believe” his wife also stems, at least in part, from the long-standing rivalry that has been building between the two men ever since Jacques started bending Pierre II’s ear with his serpentine counsel. Although Jacques might have appeared as a “true” friend to Jean, his allegiance to Pierre II becomes quite apparent when he rolls up to Jean’s property to come collect on some unpaid debts. Feudalism and all that rot. Jacques’ interaction with Jean regarding the debt also offers a scene that feels reminiscent of the present with talk of the plague cutting down the workforce and Jean scratching his head as to how the other vassals were able to pay Pierre II so readily. Jacques replies, “Because I had to insist.”

Luckily for Jacques, at this particular moment in time, all of Jean’s frustration and contempt is reserved for Pierre II before he realizes that the real culprit, at least roundaboutly, for his many woes is Jacques. This includes the allocation of a certain coveted property called Aunou-le-Faucon to Jacques from what should have belonged to Jean after marrying Marguerite (formerly de Thibouville). For it was part of her dowry before Jacques started to put the pressure on her father, Robert (Nathaniel Parker), to use it to pay back his debts to Pierre II.

In some sense, there is the Patrizia Reggiani (Lady Gaga) way in Marguerite carrying on about Aunau-le-Foucon to Jean, who tries his best to make her forget about it by saying, “It’s a pity Pierre took that Estate from your father.” On this note, what’s perhaps immediately noticeable about The Last Duel’s superiority to House of Gucci is that it is a French story without American actors trying to speak in English with a French accent. Because, unlike Italians, the French are not so forgiving of such slights.

Based on Eric Jager’s 2004 book, The Last Duel: A True Story of Trial by Combat in Medieval France, the title comes, obviously, from the fact that this was the last duel in France. Or at least the last one legally decreed by Parlement. Like the book used as the basis for Scott’s other 2021 movie, House of Gucci, this tome, too, prides itself on offering up scandal through a historical, “scholarly” lens. Hence, an alternate title being: The Last Duel: A True Story of Crime, Scandal and Trial by Combat. Whereas House of Gucci offers the subtitle: A Sensational Story of Murder, Madness, Glamour and Greed. The bottom line: Scott always goes for the sensational when it comes to agreeing to adaptations (see also: All the Money in the World). And with his gift for directing sweeping epics, this should come as no surprise by now.

We see things from Jean’s perspective first as we go back sixteen years to the Battle of Limoges on 19 September 1370. After Pierre’s army loses at the Battle of Limoges, we then flash forward to Fort Bellême 1377. And in, Chapter Two: The Truth According to Jacques Le Gris, we start back at the Battle of Limoges from his perspective, during which we see Jean foolishly defy Pierre’s orders to hold the bridge so as not to let Limoges fall. But Jean, being stubborn and proud, doesn’t take direction all that well, seeming to survive on brutishness alone.

The frequent jumps in time are, of course, indicative of just how overarching the saga is. And as all great sagas, rife with drama and betrayal as they are, it takes many decades for a denouement to finally reach its crescendo. That crescendo being a duel watched in a public arena near Notre-Dame. And, speaking of that presently still-defunct architectural icon, one of the most fascinating aspects of The Last Duel is to see how it looms in the background at certain moments, still under construction. The edifice’s struggle time and time again, to come together, seems like a loose foil for Marguerite in the wake of her rape. It is also with a semi-constructed Notre-Dame in the background that Jean hears news of his father’s death just after appealing the decision to deny the land parcel as part of his wife’s dowry. When his mother, Nicole (Harriet Walker), tells him she’ll have nowhere to go now, Jean is shocked to learn it’s because he will no longer be taking over his father’s captaincy as a result of starting this little squabble over Aunou-le-Foucon.

Jean insists it was the right thing to do despite the results now yielded. His mother snaps back, “Right? There’s no right. There is only the power of men.” Here, too, Jean foreshadows Nicole’s reaction to Marguerite deciding to report her rape instead of sweeping it under the rug. Nicole rebukes her with far more ferocity when she says, “Marguerite, why have you done this?” Marguerite asserts, “I am telling the truth.” Nicole rebuffs, “The truth does not matter… I was raped. And despite my protestations and my revulsion, did I go crying to my Lord, who had better things to worry about?” As though she needs to spell it out, Marguerite reminds, “What happened to me is wrong.” Jean’s mother balks, “Men like Le Gris take women when they want and how often they want. Who do you think you are?” And sadly, this is a still-lingering medieval mindset of not just men, but women as well.

Along with the idea that women are worth little more than being “ovens” with which a man can pull out his heir. Which is why Jacques is quick to remind Jean in the first act of the film, when he decides to go to battle again, that he’s lost his son and wife to the plague. Putting none too fine a point on it, he declares, “You have no heir. If you die, all you have will revert to Count Pierre.” Jean returns, “Jacques. I. Am. Broke. I need money.” Yes, even the well-to-do must sing for their supper now and again, and Jean does just that before encountering Marguerite when we then flash forward to Normandy 1380 on the battlefields. After winning, Jean finds himself enjoying the “shelter and vittles” of Sir Robert de Thibouville. Rather than being “grateful” for his charity, Jean simply asks, “Did he not side with the English against us at Poitiers?” Despite his distaste for de Thibouville, he certainly has no issue with his daughter, Marguerite, and the two quickly make marriage arrangements.

Alas, Marguerite might have been better off being deemed as a spinster for as tactless as Jean turns out to be—a classic example of how money can’t buy class as he rages through the region verbally assaulting the name of Pierre II and Jacques, eventually confronting them directly at a celebratory banquet. The perspective of what “really” went down there doesn’t arrive until Jacques’ side of the story in Chapter Two: The Truth According to Jacques Le Gris.

After Jean’s outburst at the count and a year of being blacklisted among all the right social circles, Jean and Marguerite make an appearance at a celebration of Crespin’s (Marton Csokas) newborn male heir. It is here that Jacques is instructed to kiss Marguerite as a sign of good faith and a symbol of reconciliation among the houses. But Jean hasn’t learned his lesson re: whatever Jean wants, Jacques ends up getting. And that’s going to be Marguerite.

In the wake of the party, we flash forward again to Scotland 1385. After fighting in a situation that would have sealed any other man’s death warrant, against all odds, Jean triumphs and we then join him in Paris 1386, where the Notre-Dame cathedral looks no closer to being complete. Seeking what he’s owed for battle, he leaves Marguerite at their isolated home, instructing his mother not to leave her unattended while he’s gone. This being the worst possible person to entrust his wife with as she patently doesn’t like Marguerite—mainly because she hasn’t “produced” an heir. So what good is she to anyone?

Especially after becoming “damaged goods.” Upon learning that Marguerite was raped by Jacques while he was away in Paris, Jean knows the only way to get true justice is by legally challenging Jacques to a duel. After placing his glove down during the hearing before Charles VI (Alex Lawther, of all people) in a bombastic display of that intent to challenge, we soon transition to “Chapter Three: The Truth According to Lady Marguerite.” It begins with about an hour left in the movie, with the words “the truth” deliberately left to linger on the title card. It is from this female perspective that we will at last understand what really happened, and be loosely met with the present-day chestnut, “Believe women.”

Incidentally, earlier in the film, at the House of Peter II, Count of Alençon a.k.a. Pierre d’Alençon, Pierre reads from The Book of Love (other popular titles of the day are also name-checked in the film, including “The Romance of the Rose” and “Perceval’s Courtesy”), reciting, “A new love expels an old one.” Maybe that’s the case for Marguerite with her child, one that finally comes amid all this chaos and one that could very well be the product of her rape. The presence of this newborn boy prompts her to at last fully see Jean for what he is: another brute. And maybe some part of her hopes that she can help raise a new generation of men through her own progeny. Or maybe that’s still too progressive a notion for the 1300s.

In any case, back to Marguerite’s side of the story. As Jean prepares to leave the abode, a horse let out in the stables accidentally bum-rushes (very literally) the mare that Jean bought for breeding, proceeding to penetrate as Jean hurries to stop the mounting. He beats it violently as Marguerite looks on, not yet aware that it foreshadows her own fate. Jean seethes, “Not the stallion! No, not you! Not with my mare!” After the incident, Jean tells his servant, “The gates remain closed!” and “These are not trifling matters. It costs money.” He continues to chastise the help with, “Nothing would get done around here were it not for me.” Marguerite looks sympathetically at the servant.

But where was someone to look sympathetically at her when Jacques and his squire show up to the house to infiltrate and overpower her? Having to watch the scene for yet a third time, it’s even more brutal from Marguerite’s vantage point—for there are no “sugar coating” camera angles or other visual “cues” that might indicate she “secretly wanted it” and Jacques was just giving her the final push. When Jean returns, she tells him, with great pain, what happened. All he can say is, “Can this man do nothing but evil to me?” Totally discounting the evil that was done to her.

Marguerite does well enough not say anything about his insensitivity, declaring instead, “Jean, I intend to speak the truth. I will not be silent. I have no legal standing without your support.” After reluctantly agreeing, he once again ignores her trauma by taking off his pants and demanding, “Come. I will not allow him to be the last man to have known you.”

At the court proceedings, no detail is spared, including questions as to whether or not Marguerite ever experiences “the little death” with her husband. Earlier in the movie, she admits to her doctor, “I’m not certain I’m experiencing ‘the little death,’ as they say.” Yes, that’s really what they should call orgasms still, even beyond France.

“A rape cannot cause pregnancy. This is just science,” decrees one of the judges, in yet another indication of the horrific and archaic times a woman like Marguerite endured. But their cockamamie logic is only a help to Marguerite, for it means they can’t assume her child, born on 28 December 1386, could be Jacques’ own as well, therefore “indicating” she orgasmed with him and not Jean… a.k.a. she “enjoyed” her assault.

As the third act climax occurs in the form of a jousting-heavy duel—taking us back to the scene we saw at the outset—Marguerite awaits among the crowd with her feet fettered. For if her husband does not win, it will be assumed God’s will, as well as proof that she was lying all along. Thus, the punishment being to burn her at the stake for speaking out at all. So much of which still occurs on a more obviously metaphorical level in the current epoch (even post-#MeToo).

Upon Jean winning the duel (though it is extremely touch-and-go for a while), Marguerite is ephemerally content until she sees that the “glory” now bestowed upon him is only further feeding his false ego. She walks behind him through the crowded streets of Paris toward Notre-Dame, watching the revelers worship him as the body of Le Gris is strung up for all the city to see.

In typical “historical drama directed by Ridley Scott fashion,” we’re given a few epilogue title cards, including how, after Jean died in the Crusades, “Marguerite de Carrouges spent thirty years living in prosperity and happiness as the lady of the estate at Carrouges.” The kicker in the final sentence of the epilogue? “She never remarried.” And why would she? It’s an epilogue tantamount to the headlines about a 109-year-old woman saying, “My secret to a long life has been staying away from men.” Because men are nothing but a woman’s bane, and putting out without any hope of the little death, like Marguerite, is utterly without reward (save for the male in the equation, naturally). The only reward for Marguerite now is that her story could be told in a manner that lends her the credibility she (and all women who have gone through sexual assault) deserves. Even if telling it in a Rashomon style does have the potential to infer, especially to a more misogynistic audience, that her story might have “holes.” But, no matter what one’s “perspective” (a.k.a. “justification”) is, a rape is a rape.