Remaking anything from the Alfred Hitchcock oeuvre is always an emboldened move. And yet, at the same time, in the present climate of a total lack of film snobs, there has possibly never been a better moment to repurpose the auteur’s material. Thus, someone as wet behind the ears as Ben Wheatley (a name you likely haven’t heard until now) could take the helm of a project associated with such a film heavyweight (no weight joke about Hitchcock intended). His only previous major endeavor being another book adaptation, J.G. Ballard’s High-Rise (released in 2015), Wheatley directs a script from Jane Goldman, whose credentials pack more of a punch–with prior projects including Stardust, The Debt, The Woman in Black, Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children and Kingsman: The Golden Circle.

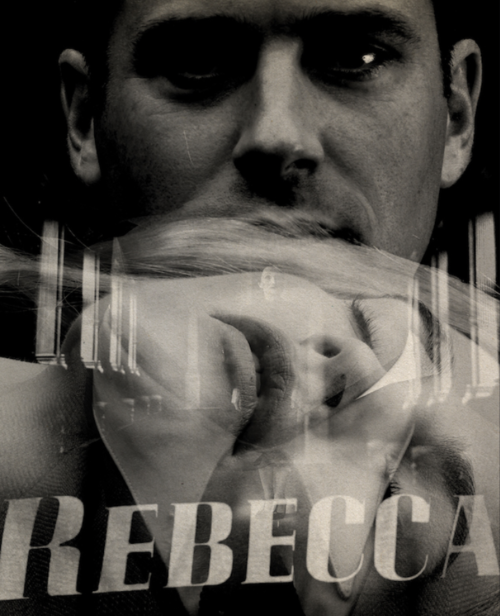

It is Goldman’s mastery in the genre of suspense, intermixed with a touch of thriller and action flair, that renders Rebecca as a worthy remake. Hitchcock purists, of course, will never be able to see it that way. And, no, there will never be another director who can achieve what he did with suspense. The Master of the Macabre, the Scion of Psychology, the Brute of Brutality. But if we put that aside for long enough, we can see that the amendments and updates made to Rebecca, despite the fact that it still takes place during the same time period of roughly 1936, very much lend it a fresh perspective (a woman “allowed” to drive the car, for heaven’s sake! That sort of thing wouldn’t have happened until To Catch a Thief in 1955). That proverbial modern appeal. For starters, Goldman’s use of voiceover from the perspective of the “Unnamed Woman” (played in this case by Lily James, coming into her own more than ever) lends her more texture and personality than she was given when Joan Fontaine performed the part. The calculated decision not to give the “second Mrs. de Winter” her own name plays into the overshadowing, monumental nature of Rebecca. The dead first wife of Maxim de Winter (Armie Hammer in 2020, Laurence Olivier in 1940) whose spectral presence still looms large at Manderley, the postcard-like estate on the coast of England where they live.

With every room filled with some trace of her–at the bare minimum, this includes one of her monogrammed “R” items–Mrs. de Winter II can hardly compete with her ever-looming legend. It doesn’t help matters that the head of the household staff, Mrs. Danvers (Kristin Scott Thomas in 2020, Judith Anderson in 1940), is all too keen to preserve every last essence of Rebecca, the apex of her devotion being showcased in a particularly creepy scene during which she sensuously caresses Rebecca’s black negligee and urges Mrs. de Winter II to do the same. In addition to building upon Mrs. Danvers’ unique brand of psychosis, Goldman also layers more “character analysis” scenes during the first portion of the film, the period when Maxim and Mrs. de Winter II are entertaining their budding romance in Monte Carlo. At the time of their encounter, the soon to be Mrs. de Winter II is being paid as a “lady’s companion” to the insufferable, hen-like Mrs. Van Hopper (Ann Dowd). Yet still, Mrs. de Winter II, for as much naivety as she has lost over the course of the narrative can only seem to see the best in people as she looks back on the events with the voiceover, “I can see the girl I was so clearly, even if I know longer recognize her. And I wonder what my life would have been without Mrs. Van Hopper. Without that job. Funny to think that my existence hung like a thread upon her curiosity. If it wasn’t for her, I would never have gone to Manderley…”

And it’s true, without the clucking, harsh Mrs. Van Hopper (just as clucking and harsh in the original, but not quite as overtly so, because it was not as permissible to show the upper class for what they were back then), Mrs. de Winter II would never have encountered–no matter how gawkily–Maxim. Aristocratic, mercurial Maxim. What’s more, Mrs. Van Hopper falling ill gives her paid “companion” ample time to feign taking tennis lessons when instead she’s really gallivanting along the French Riviera with Maxim in his car. It is during this segment that Goldman puts her own stamp on the dynamic. Whereas in the original film, Mrs. de Winter II seems to have no distinct personality of her own other than that of a bumbling and meek clod who manages to charm Maxim with her antithetical qualities to Rebecca, in this one her unrefined charisma is more nuanced and studied. As though Goldman deliberately wanted to imbue her with more of a “backstory” than she was originally given–what with so much more time lent to building upon the lore of Rebecca, which still remains omnipresent here, but not quite so.

Mrs. Danvers, too, is infused with more texture, most markedly during a scene in which Mrs. de Winter II tries to fire her while she’s sitting in her maid’s quarters, only to be manipulated by Danvers with a sob story about how Rebecca had been her whole world–how she had practically been a mother in addition to a best friend to her, so how could Mrs. de Winter II ever possibly expect to replace the “real” Mrs. de Winter?

The leeching lecher that is Jack Favell (Sam Riley), Rebecca’s cousin and lover (because again, it was a different epoch), also gets more “interactive” screen time in his exchanges with Mrs. de Winter II, who makes the mistake of falling prey to his coquetry by agreeing to take a horse ride with him (something that certainly doesn’t occur in the original). The revelation of this information from one of the servants sets off Maxim’s (as of yet unknown to Mrs. de Winter II) notorious temper. Indeed, Laurence Olivier is obviously far better at delivering these diva-like tantrums, but Armie Hammer does his best. One only wishes that Goldman had not allowed him to even attempt the classic line, “It’s gone forever… that funny, young, lost look I loved won’t ever come back.” That she had instead seen fit to allow Armie to instead keep for himself: “Please promise me never to wear black satin or pearls… or to be thirty-six years old.” But one supposes such a line is too sexist in the present, and it’s very clear Goldman wanted to imbue Rebecca–the character and the film–with a more feminist slant. This being done through the mouthpiece of Mrs. Danvers decrying, “She despised you all. The men in London, the men at the Manderley parties. You were nothing but playthings for her. And why shouldn’t a woman amuse herself? She lived her life as she pleased, my Rebecca. No wonder a man had to kill her!”

Here Mrs. Danvers also gets to the core of the symbolic punishment behind Rebecca ultimately dying of gynecologic cancer. After all, if you’re a “little whore” catting around “as you please,” of course “karmic justice” (as envisioned by the patriarchy) will see fit to deliver your comeuppance with a slow, painful burn to your “WAP.” In this sense, Goldman does solidify her distinct take on the material, in addition to sustaining the Shirley Jackson aura (specifically The Haunting of Hill House) bequeathed to Manderley, most notably at the beginning and end of the film. That larger than life space that was only matched in stature by Rebecca herself. The structure that will continue to haunt no matter what state of disrepair it falls into.

Mrs. de Winter II is aware of that much, which is why she prefers to take her marriage on tour in the end, never staying in one place too long so as to keep the relationship forever fresh, and forever hers and Maxim’s alone. As though to stay in one place might allow Rebecca’s ghost enough time to find them. Though naturally we know it can never truly leave Manderley. Just as Hitchcock can never be taken out of it either, though one must at least give this Rebecca its fair amount of due as far as Hitchcockian remakes go. For it isn’t so prosaic as to do a shot-for-shot re-creation à la Gus Van Sant with Psycho, nor so liberty-taking as to pull an Andrew Davis with A Perfect Murder (a.k.a. Dial M For Murder). In truth, it strikes a Goldilocks balance.