Of all the numerous and controversial French political figures, it is Napoleon Bonaparte who remains foremost in the minds of the French and non-French alike. A(Bona)part(e) from Marie Antoinette, there is no other icon in French history who still continues to fascinate so enduringly on a “pop” level. To that end, the opening to Ridley Scott’s latest historical drama (spoiler alert: The Last Duel was much better), Napoleon, fittingly combines the two polarizing leaders in a scene that overtly foreshadows what will become of Monsieur Bonaparte after his own ascent.

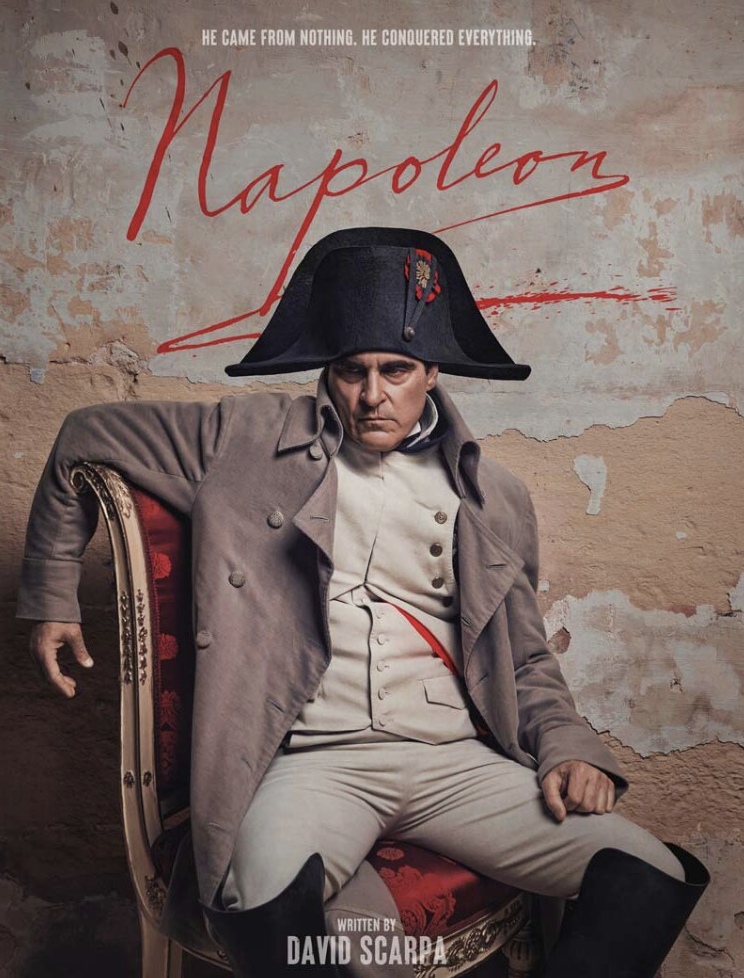

And yet, watching Antoinette’s head get decapitated in front of a salivating mob doesn’t appear to be enough of an indelible image to quell Napoleon’s (played impressionistically by Joaquin Phoenix) ever-mounting hubris. Indeed, one might say that the only “message” ever established in Napoleon shines through in this lone (and entirely fabricated) scene foretelling of how powerful people are always taken down by this quintessential deadly sin. Napoleon, of course, assumes he is nothing like the monarchs guillotined as the pièce de résistance of the French Revolution. For a start, he’s a Corsican, which automatically makes him a “mutt brute” in the eyes of “real” French people/nobility. After all, it was only one year after Napoleon’s birth that the Republic of Genoa ceded the island to France, with the latter conquering it the year Napoleon was born, 1769. Which made his commitment to France later on so ironic. For he was fundamentally Italian. After all, not only was Corsica originally “possessed” by Italy before France, but any “blue blood” he had stemmed from being descended from Italian nobility (hence, his true last name: Buonaparte). Ergo, another fallacy of Scott’s film via making the tagline so posturing and oversimplifying as to be: “He came from nothing. He conquered everything.”

In any event, perhaps this perception of himself as a “royal” is why he saw his “ownership” of France as some kind of “divine right,” in the end. For even despite “supporting the ideals” of the French Revolution that led to the abolition of the monarchy, Napoleon still couldn’t resist the temptation and seduction of “ultimate power.” No more than he could resist the charms of Joséphine de Beauharnais (played here by Vanessa Kirby, though the role was originally intended for Jodie Comer, who also starred in The Last Duel). A woman who many a man (both then and now) would readily call a “slut.” Indeed, that’s the word used by Napoleon in the film after he’s confronted by The Directory over his “desertion” during the Battle of Egypt upon hearing news of Joséphine’s affair with Hippolyte Charles (Jannis Niewöhner). At which time, he gives them a long spiel about how, if anything, they’re the ones who have deserted France, while Napoleon has returned to restore it to its natural state of glory. This includes, naturally, another coup, with Napoleon and his coterie of co-conspirators, Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand (Paul Rhys), Joseph Fouché (John Hodgkinson), Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès (Julian Rhind-Tutt) and Roger Ducos (Benedict Martin), taking over by force when their “whim to rule” isn’t met with unanimous acceptance. So it is that Napoleon repeats the same cycle of oppression that the French revolutionaries vowed never to tolerate again after toppling the monarchy.

Turns out, Napoleon seemed to think the word “emperor” instead of “king” somehow made his imposed rule more “palatable,” even going so far as to impudently crown himself at the coronation. An emperor willing to “get his hands dirty,” as it were. Of course, this is just one of the many “flourishes” (picked up from a legend surrounding the coronation) that Scott has added to the tale of Napoleon as told through a “Hollywood lens,” one that has been deemed as patently anti-French and pro-British. Scott did little to quash that assessment when he said, in response to negative French reviews of the film, “The French don’t even like themselves.” However, if Napoleon was any indication to be held up as a benchmark, that’s simply not true at all. And it’s perhaps because they hold themselves and their history in such high regard that this film is particularly offensive, namely as Americans speak in attempts at a French accent. This, in turn, also adding to the overall absurdity of the storytelling (also present in House of Gucci when Americans were speaking with “Italian” accents, Lady Gaga being among the worst of the offenders).

Scott stated at the outset of his announcement to direct a film about the emperor, “He came out of nowhere to rule everything—but all the while he was waging a romantic war with his adulterous wife Joséphine. He conquered the world to try to win her love, and when he couldn’t, he conquered it to destroy her, and destroyed himself in the process.” Absolutely none of that comes across in the choppy, disjointedness of Napoleon, which wants so badly to cover such a multitude of themes and grounds that it ends up saying little at all. It is merely a “retelling.” And one with many historical inaccuracies at that (this being another primary complaint about the movie). Not least of which, of course, is the fact that Napoleon wasn’t present at Antoinette’s beheading.

Written by David Scarpa (who also penned the script for Scott’s All the Money in the World and his upcoming sequel to Gladiator), the lack of focus on any one aspect of the vast entity that is Napoleon often causes issues in terms of structure and “meaning.” More often than not, it feels as though things are “just happening” without any buildup to it, let alone a sense of cause and effect.

Funnily enough, Scott’s first feature film, The Duellists (released in 1977), is centered around the Napoleonic Wars and homes in on two rival French officers named Gabriel Feraud (Harvey Keitel), a devoted Bonapartist, and Armand d’Hubert (Keith Carradine), an aristocrat. Spanning twenty years, the film manages to come in well under two hours and covers far more ground than Napoleon can seem to. For it suffers from the same problem as its eponymous dictator: it’s too ambitious and, ultimately, can’t make its mind up about what it wants to achieve. This is likely a result of the script not being based on any specific source material. Whereas Scott seems to be at his best when he works with a script that’s based on an adapted screenplay. This, it should go without saying, does not apply to the odious House of Gucci. In fact, the latter movie and Napoleon suffer from many of the same issues, including, but not limited to: 1) things “just happen” for no reason, thereby making plot and character development all but nil and 2) Scott has become somewhat notorious for letting other cultures tell stories that don’t belong to them. Because, obviously, if any culture should get to tell the story of Maurizio Gucci and Patrizia Reggiani or Napoleon and Joséphine, it should goddamn well be the Italians and the French, respectively. To that end, the real Napoleon biopic to see is 1927’s Napoléon. Not so coincidentally, the film was slated for another restoration and rerelease this year—as though the French wanted to remind a Brit like Scott that it’s absolutely galling to presume to tell the story of their emperor.

As for someone like Marie Antoinette, who has been fixated upon in cinema repeatedly by all manner of nationalities, it was Sofia Coppola (via Kirsten Dunst) who claimed the most memorable ownership over her in recent years. This achieved by fully “pop-ifying” both her personage and the script and soundtrack. Opting to contain the narrative with far more dexterity than Scott is able to with Napoleon. In point of fact, one wonders if this film might not have been better off if Scott and Scarpa had chosen to go full-tilt camp with it (alas, that’s not really something two straight men are capable of, which means casting Peter Dinklage in the lead role would have been out of the question). For there are slight “glimmers” of such campiness in Napoleon’s lecherous exchanges with Joséphine (e.g., Jo opening her legs in front of “Boney” and saying, “If you look down here you’ll see a present, and once you see it you’ll always want it” or Napoleon making animalistic noises at her after she’s just had her hair “set,” finally prompting her to give in to his sexual desires). In truth, the entire movie should have simply had one focus: Napoleon and Joséphine (likely earning it the same straightforward title). That way, there would have been a firmer anchor to the film as opposed to this sense of being “all over the place” (though it is literally that as well, with Scott showing us the far-reaching backdrops of Napoleon’s various famed battles). And, again, with no real “lead up” to anything. Case in point, the sudden decision to include Tsar Alexander’s (Édouard Philipponnat) romantic overtures to Joséphine after her divorce from Napoleon. Overtures that were more likely politically motivated than genuinely romantic.

But such is to be expected from a film fraught with embellishments. Including the much-praised battle scenes themselves, accused by Foreign Policy’s Franz-Stefan Gady of being nothing more than “a Hollywood mishmash of medieval melees, meaningless cannonades, and World War I-style infantry advances.” Adding, “For all of Scott’s fixation on Napoleon’s battles, he seems curiously disinterested in how the real Napoleon fought them.”

Nonetheless, to any condemnation of his seemingly flagrant disregard for accuracy, Scott snapped (in an article for The New Yorker), “Get a life.” For some, though, Napoleon/Napoleonic history is their life. While, for others, quality cinema is. On both counts, Napoleon cannot quite deliver. Falling shorter than the man it pays homage to.

[…] Genna Rivieccio Source link […]