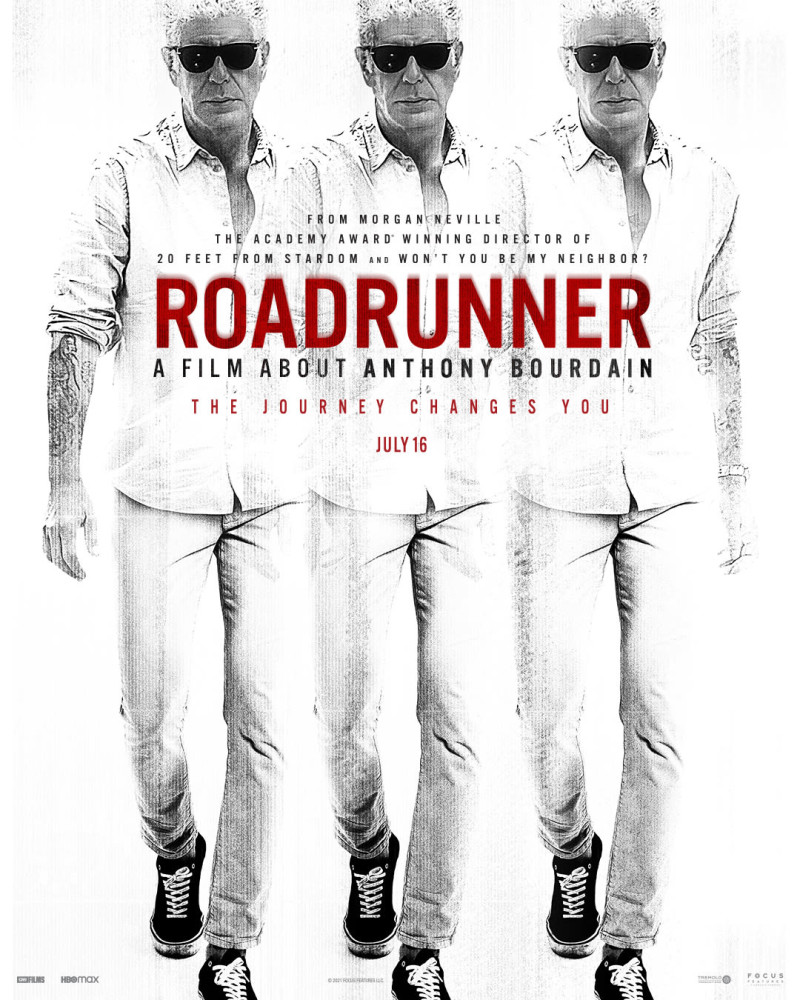

It was never a secret that Anthony Bourdain was not a particularly “rosy” sort of guy. But no one ever imagined that his perpetual state of curmudgeonliness would result in suicide. That his lowest low yet in the manic depression he suffered from would lead to such a rash and irrevocable action. In Morgan Neville’s (fresh from the directorial highs of Won’t You Be My Neighbor? and They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead) Roadrunner: A Film About Anthony Bourdain, the evolution of Bourdain from shy, insecure chef with a chip on his shoulder to internationally known TV personality with an “asshole” persona that started to stick is explored through the lens of his meteoric rise as compared to the slow demise of his personal life.

Married at the time of his initial fame to Nancy Putkoski, a girl he met in high school, their union fell apart as Bourdain spent more time on the road to film A Cook’s Tour and Putkoski chose to shy away from the limelight—which meant, ultimately, divorcing the evermore illustrious Bourdain. While the documentary doesn’t inspect it as deeply as his subsequent major relationships, this would seem to be the first major letdown of his adult life—in terms of letting himself down by not being able to prove that romance can last, the fairy tale is real, etc. For yes, like most cynics, Bourdain, deep down, wore that veneer to mask how hopeful a person he was. But hope, as we all know, tends to disappoint time and time again, hence the creation of a cynic a.k.a. undercover sanguine optimist. Oh, the shame of being such a thing when life shows you what it is every day. Especially someone who saw as much as Bourdain.

The suffering and the gross discrepancies of wealth that make this world such a nonsensical horror show undeniably affected Bourdain’s previously myopic worldview (for he was just another insulated “Manhattan Guy”—like the one in Sex and the City—before he caught his big break). Early on in the film, after acknowledging Bourdain’s desire to be a great writer in the spirit of someone like Hemingway yet instead being led down the last path he would have deemed respectable thanks to his memoir, Kitchen Confidential, Neville reveals the sensitivity of a man who, despite a gruff exterior, couldn’t handle something like what happened when they were filming an episode of No Reservations in Beirut and war erupted as Israelis began bombing the city (in what would become known as the 2006 Lebanon War—or the July War, to the Lebanese). While explosions and violence took place just outside their hotel, Bourdain and his crew could do nothing but “relax” at the poolside and wait for it to pass. This being the single moment that best sums up Bourdain’s perspective on his own privilege, and the guilt he felt about it.

Another No Reservations episode Roadrunner touches on is “Haiti,” during which his attempt to give leftover food to the destitute in the area backfires spectacularly as it causes a Lord of the Flies-esque battle for survival. Bourdain’s naïveté about believing that everyone would want to “share and share alike” in a climate of such scarcity also hit hard in terms of him fathoming just how “undeservedly lucky” he was. This, of course, fed into his obvious case of impostor syndrome. It seemed he spent his entire famous life waiting for the other shoe to drop, and for people to realize he was a fraud. In the rebranding of his existence that began in 2007 upon marrying Ottavia Busia (who appears in the documentary and has spoken out against its use of AI despite Neville countering that she previously approved), it appeared as though Bourdain might be able to finally buy into his new identity. Particularly one he never imagined he would be fit for: father. Also born the same year Bourdain married for the second time, his only child, Ariane Bourdain, would be just eleven years old when her dad “checked out” of a certain French hotel in a less conventional manner.

Her birth paves the way for Neville to focus on another key area of Bourdain’s depression: not living up to his own high expectations for himself of being the ultimate “family man.” Of being able to deliver on the “white picket dream.” Though he tried diligently at the outset to do so, perhaps overcompensating with the foreknowledge that he would have to let all the plates drop (food metaphor) again in order to focus on the one thing he seemed truly born for: TV glory. More salt in the wound of not fulfilling an original ambition of being something like a Great American Author, complete with the angst, drug addiction and chain-smoking of his erstwhile misspent youth.

Ah, and talking of that addiction, among the many people interviewed, including David Chang, David Choe, Josh Homme, Eric Ripert and John Lurie, the sense one gets is that Bourdain was a man of extremes. Someone who couldn’t feel anything unless he felt it very intensely. Constantly seeking new highs to fill the void. This, of course, all goes back to his days of heroin addiction—fully aware of the risk involved in “taking up the habit,” but not caring because he seemed to intuit that the drug would appeal to his need for an extreme on the emotional spectrum. And yet, living out his entire life that way would prove impossible. It is here we come to the portion of the documentary where Asia Argento shows up. Clearly, Bourdain had started to develop a taste solely for Italian women. As well as a masochistic taste for being the one to reveal way too much enthusiasm in a relationship. And indeed, there are numerous cringe-y moments rehashed during this dalliance, especially when Bourdain takes up the #MeToo movement as his own cause because of Argento.

While the film goes pretty far in essentially saying Argento pulled the proverbial trigger on Bourdain with her lack of “discretion” (a.k.a. she was photographed in the tabloids with another man), it reins itself in again when one commentator declares that, at the end of the day, “Tony” made the decision himself. In a moment of rage and weakness that couldn’t seem to be channeled in any other fashion. It might seem unfathomable to those who have never sunk to that point, but for those who have, it’s only too understandable.

Naturally, rather than focusing on what the film says about Bourdain as it relates to the human condition, there has been more audience and critic focus on the use of AI to recreate Bourdain’s voice during, reportedly, three instances in the documentary. Only one that Neville would call out specifically: the part where there is a voiceover of him reading an email he wrote about his journey to Hong Kong. Whatever other segments might have been “manipulated,” it doesn’t change that Roadrunner takes a deep dive into the psyche of a man at last unable to outrun his pain with the salve of piling on more extremes. The movie, fittingly, wields The Modern Lovers’ song of the same name, during which lead singer Jonathan Richman sings, “I’m in love with Massachusetts.” It seems appropriate, considering Provincetown was where Bourdain first crystallized his notion of turning his passion for food and cooking into a career. Alas, even real roadrunners reach the end of their road eventually. With no distance left to run.