As Hollywood prepares itself for the Academy Awards under the dark pall of an unhinged, anti-Californian president and an ongoing recovery from the most devastating wildfires in L.A. history, there has never been more fear and uncertainty in the entertainment industry than there is now. Because, yes, as Jane Fonda pointed out during her acceptance speech for a Lifetime Achievement Award at the SAG Awards, this is a time that, for Hollywood, is veering very close to McCarthy-era suppression. Closer than it should ever be in an era as “modern” as the 2020s. But that isn’t the only element of ever-increasing uncertainty in this particular industry. As Oscar nominee Sean Baker pointed out at the Fortieth Annual Independent Spirit Awards on February 22nd, the added sense of the bottom constantly dropping out stems from even “successful” filmmakers not being able to earn a livable wage.

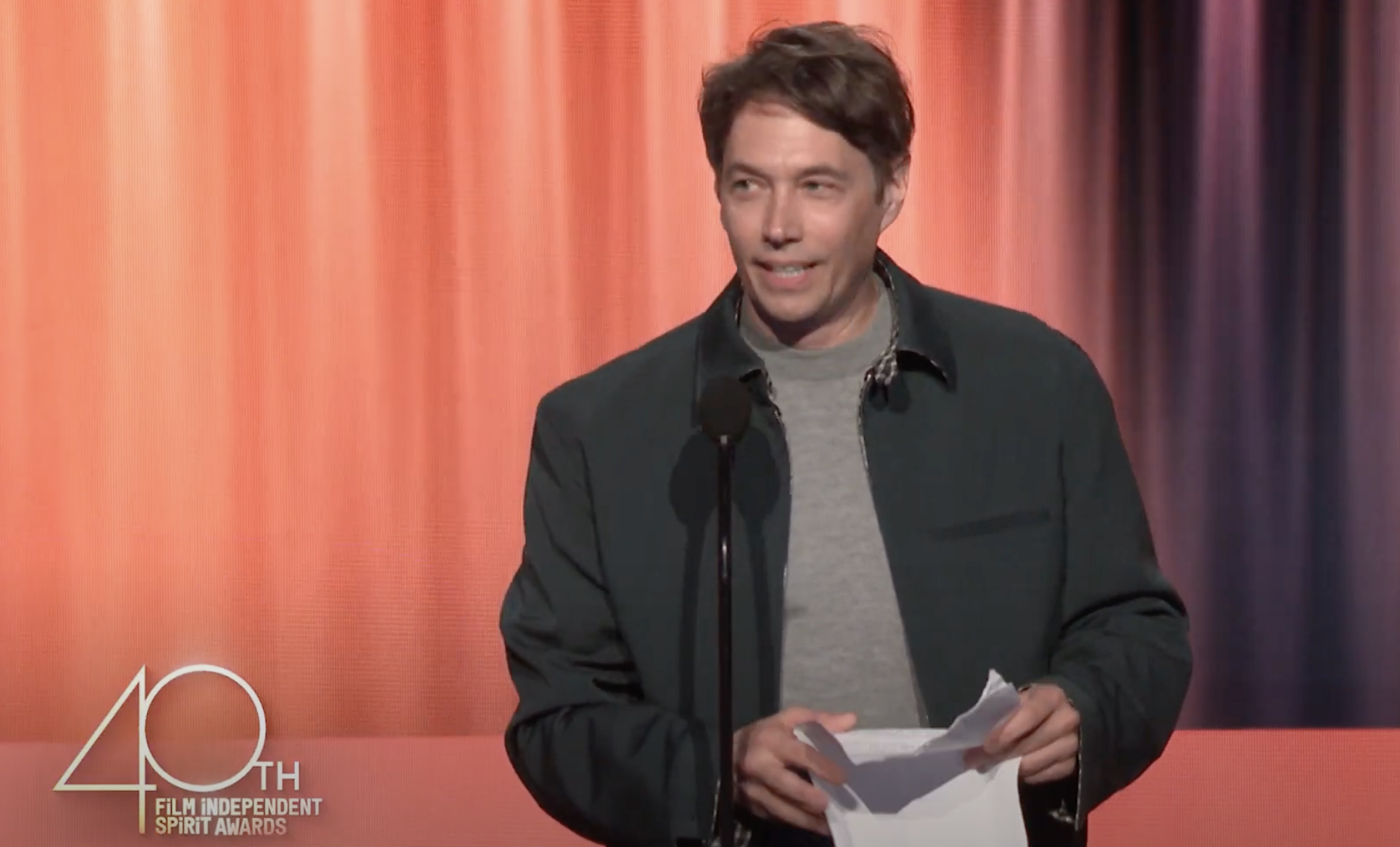

Taking the opportunity to call out one of the biggest absurdities of working in film (particularly independent film)—as Chappell Roan recently did for the music industry at the 2025 Grammys—Baker read from a lengthy speech while accepting the award for Best Director (Anora would win the most awards of the evening: Best Director, Best Lead Performance and Best Feature). It went as follows:

“I just want to use this moment to speak about the current state of indie film. Specifically how it applies to creatives. Indie film is struggling right now more than ever. Gone are the days of DVD sales that allowed for greater risk to be taken on challenging film. That revenue stream is gone and the only way to see significant backend is to have a box office hit with profits that far exceed what any of our films will ever see unless you are Damien Leone and strike gold with a franchise like Terrifier. But as we all know, that’s an extreme rarity. For me, and I think for many of my peers, we’re lucky. The average number of years dedicated to making a film is around three. I’m gonna say three, I think most of us have worked a lot longer on our films, but let’s go with three. If you’re a writer-director trying to break in right now, there’s a good chance you’re making a film for free or making next to nothing on production or sale. How do you support yourself with little or no income for three years? Let’s say you’re lucky enough to be with the guilds. Take the DGA and WGA minimums and divide them by three. Take out taxes and possibly percentages that you owe your agents, managers and lawyers, and what are you left with? It’s just simply not enough to get by on in today’s world. Especially if one is trying to support a family. I personally do not have children, but I know for a fact that if I did, I would not be able to make the movies that I make. Why am I talking about this today? Because I am an indie film lifer and I know that there are other indie film lifers in this room. Those who don’t see indie films as calling cards, those who don’t make these films to land a series or a studio film. Some of us want to make personal films that are intended for theatrical release with subject matter that would never be greenlit by the big studios. We want complete artistic freedom and the freedom to cast who is right for the role, not who is forced to [be] cast [based on] box office value or how many followers they have on social media… The system has to change because this is simply unsustainable. We are creating product that creates jobs and revenue for the entire industry. We shouldn’t be barely getting by. Creatives that are involved with projects that span years have to begin getting much higher upfront fees. And again, because backend simply is not—it can’t be relied upon any longer. We have to demand that. If not, indie films will simply become calling card films, and I know that’s not what I signed up for. So let’s demand what we’re worth. I know that if you’re in this room, you’ve proven that you’re worth it, so let’s not undervalue ourselves any longer.”

Baker’s rallying cry to independent filmmakers is not only in line with Roan demanding stronger label support for developing artists (including and especially health care), but also comes at a time when even those in the “big leagues” are struggling to make money from their work. One could say that Brady Corbet, with his own Oscar darling, The Brutalist, falls into this category. To boot, A24, which distributed film in the U.S. (along with other recognizable juggernauts including Universal Pictures and Focus Features in the U.K.), is hardly classifiable as “indie” at this juncture (with comparisons in recent years to how the production company has become a Bizarro World kind of Marvel Studios). Which means, in a sense, that it should have more money to throw at people like Corbet, who told Marc Maron on his WTF podcast that he has made “zero dollars” thus far from The Brutalist (this in addition to his much-underrated 2018 film, Vox Lux). While some dickheads might try to say he makes no money because his films aren’t “good enough,” the fact that the Academy came a-knockin’ this year has proven Corbet’s worth as a writer-director. So why isn’t someone like him, as Baker reminded, getting paid accordingly? Which means to say, why isn’t he (and his collaborator/wife, Mona Fastvold), at the bare minimum, getting paid by whatever studio—indie or otherwise—is bankrolling the movie to actually be able to live while working on the abovementioned three-year minimum it takes to devote oneself to completing a film?

That means, of course, the individual not having to rely on their own savings (if they have any at all) to “make it work” during the lean years of film production and even promotion. For, as Corbet also noted, he paid out of his own pocket for various travel expenses while tirelessly promoting the film, devoting so much time to this separate job in and of itself that he didn’t take on any new work while committed to seeing The Brutalist all the way through. And yes, luckily, that’s yielded a result in terms of the movie getting more and more notice and recognition. But not everyone is quite so fortunate when it comes to taking a gamble that leads to winning big. Hence, the earnestness and correctness of Baker’s plea to an industry that is getting ever more “bottom line-y” (which means a refusal to invest long-term in filmmakers and their projects—again, just as Roan also pointed out about record labels and their callous/predatory approach to musicians who are freshly starting out).

Indeed, one wouldn’t be surprised if the heads of various studios (yes, even indie ones) were to respond in a similar way to how Jeff Rabhan did to Roan’s speech in The Hollywood Reporter: “It seems Chappell Roan wants to turn labels into landlords, bosses and insurance providers? Have you ever tried to get your expenses reimbursed from a major label? Yet somehow you want them in charge of health-care claims? As if labels want next year’s winner to shout them down as ‘slumlords’ in front of 60 million viewers?” Effectively telling Roan that her call for change was “insolent” and “disrespectful” to the fat cats that feed her (even though she’s the one who feeds them by making their label money), Rabhan wasn’t through with his derisive remarks, adding, among other pedantic comments, “Demanding that labels pay artists like salaried employees ignores the fundamental economic structure of the business. No one is forcing artists to sign deals. For the one-millionth time—if they don’t like the terms, they can stay independent, own their masters and take the financial risk themselves.”

And yes, as Baker and Roan have accented of two separate arts, we’ve seen how well that’s working out for creatives’ mental health and sense of stability. But, for Baker, at least being a man has paid off (as it usually does) in this case, as no one came out against his suggestion with a full-on “think piece” addressing why he’s too stupid and naïve to understand that overhauling this aspect of the business wouldn’t work (basically because capitalism). Or being repeatedly told to put his money where his mouth is in said “think piece” (side note: Roan was more than game to prove her commitment to the cause). Or telling him that he’s a hypocrite because he’s inside the very system he condemns, making a cush enough profit from it to have no leg to stand on. Except that, no, in actuality, he isn’t. Nor is much of anyone executing the primary creative work at this level of theoretical success.