The thing about adapting a novel from Patricia Highsmith is that it almost always guarantees the film will have a high gloss feel with the trade off of a slow pace. Wim Wenders’ 1977 interpretation of Highsmith’s Ripley’s Game doesn’t offer much of the former, but plenty of the latter. Perhaps because the 70s were an unavoidably grit-laden time, Wenders couldn’t be expected to lend much in the way of lustrous cinematography à la The Talented Mr. Ripley or Carol. But maybe that’s what makes it such a standout among all the many cinematic renderings of a Highsmith work.

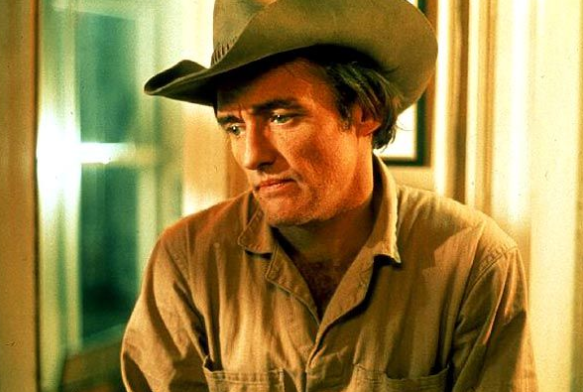

At the outset, the plot seems to be solely centered on “cowboy in Hamburg” Tom Ripley (Dennis Hopper) as he deals paintings in an illegal fashion by pawning them off as the work of a dead famous artist, when, in fact, it’s merely the work of an American mobster (Samuel Fuller) based in New York City. When Tom brings back his latest hackneyed work to subversively drive up the price at the auction, he encounters picture framer Jonathan Zimmermann (Bruno Ganz), who refuses to shake his hand after remarking judgmentally, “I’ve heard of you.” This sets off in motion Ripley’s subtle retaliation upon being asked by French gangster Raoul Minot (Gérard Blain) if he can take out another rival. Not wanting to get his own hands quite so dirty, a bemused Ripley suggests using Zimmermann for the job as he is soon to die from a rare blood disease. Minot takes this advice to heart, wielding Zimmermann’s weakness against him to make him think he’s more ill than he really is by “generously” offering him a second medical opinion in France.

Of course, the intended effect to is instill the fear of imminent death within him so he’ll act as their shooting monkey, now desperate enough to take the hit out–and maybe even another–so that he can leave his wife, Marianne (Lisa Kreuzer), and son, Daniel (Andreas Dedecke), a significant amount of money to provide for them in his absence.

As Ripley learns of Zimmermann’s eventual “progress” in the job, and his willingness to partake in another murder, he starts to get protective. Since he’s already come into see Zimmermann to get a picture framed, he uses it as an excuse to check up on him again, Zimmermann still completely unaware of his involvement in the plot he’s gotten himself into. Their quote unquote friendship attraction to each other develops naturally, with Ripley flattering, “Gantner told me you were a good craftsman. I admire that. I’ve always wanted to be able to make something with my hands. But, well, some people have it and some people don’t.” Likewise, it appears Zimmermann feels his own latent admiration for the roguish, cowboy ways of Ripley, taking inspiration for his own brash actions throughout the narrative.

Nonetheless, the illusion of forgiveness for wrongdoing isn’t always what it seems in a Highsmith plotline, making a grander statement on the complications associated with trust, even when one truly believes a person is his friend. Accordingly, Wenders’ adaptation of The American Friend is a jaded, yet accurate portrait of betrayal–whether one is convinced of loyalty proven in the past or not. It is just as Ripley states to his tape recorder (very Cooper in Twin Peaks-like) at the beginning of the film, “I know less and less about who I am, or who anybody else is.” And this sentiment has been so at least since the time of Jesus and Judas. The back is just so much easier to stab than the front, hence that famous Oscar Wilde aphorism.