Being that the U.S. in particular has always been sheltered from the sight of war—having never seen it on their soil save for rare occasions like Pearl Harbor and 9/11—“enduring” what’s going on between Russia and Ukraine at present feels like the first “moment” of its kind in an age when social media is incorporated into our everyday lives.

During the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, social media was still in a very germinal phase, and not yet hammered into our existence as though part of second nature. With the Iraq War being deemed the “frivolous” one (that is, when budget cuts required the Department of Defense to “choose”), the U.S. government cut bait on it at the end of 2011. Wanting Americans to continue to “believe” in their government and its “ideals” about “spreading democracy” (you know what else “spreads”? Disease.), the Obama administration kept funneling dividends into the budget to help fight the so-called good fight in Afghanistan even after Bush II left. It was “his” war, after all—additionally piggybacking his own personal vendetta war off of that.

Throughout this timeline, Facebook is still in its infancy, founded in ’04 and not gaining major popularity until around ’09, with 350 million registered users (beyond just its original intent of catering to students in college). Because of this “newness” to those who hadn’t learned of its “wonders” five years prior, we’re in a period where updates like, “Just made a sandwich” are deemed the best way for how the platform should be used. The political commentary, the echo chamber of hate, the potential for election tampering—that all had yet to crystallize in the Facebook realm as the “twin wars” unfolded in the 00s.

Then comes 2010: the creation of Instagram. It took far less time for the app to gain momentum than it did for Facebook, garnering a million users within two months of its existence. So naturally, Facebook acquired it for its eventual “metaverse” plans by 2012, establishing a juggernaut that will include WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger and Oculus as well.

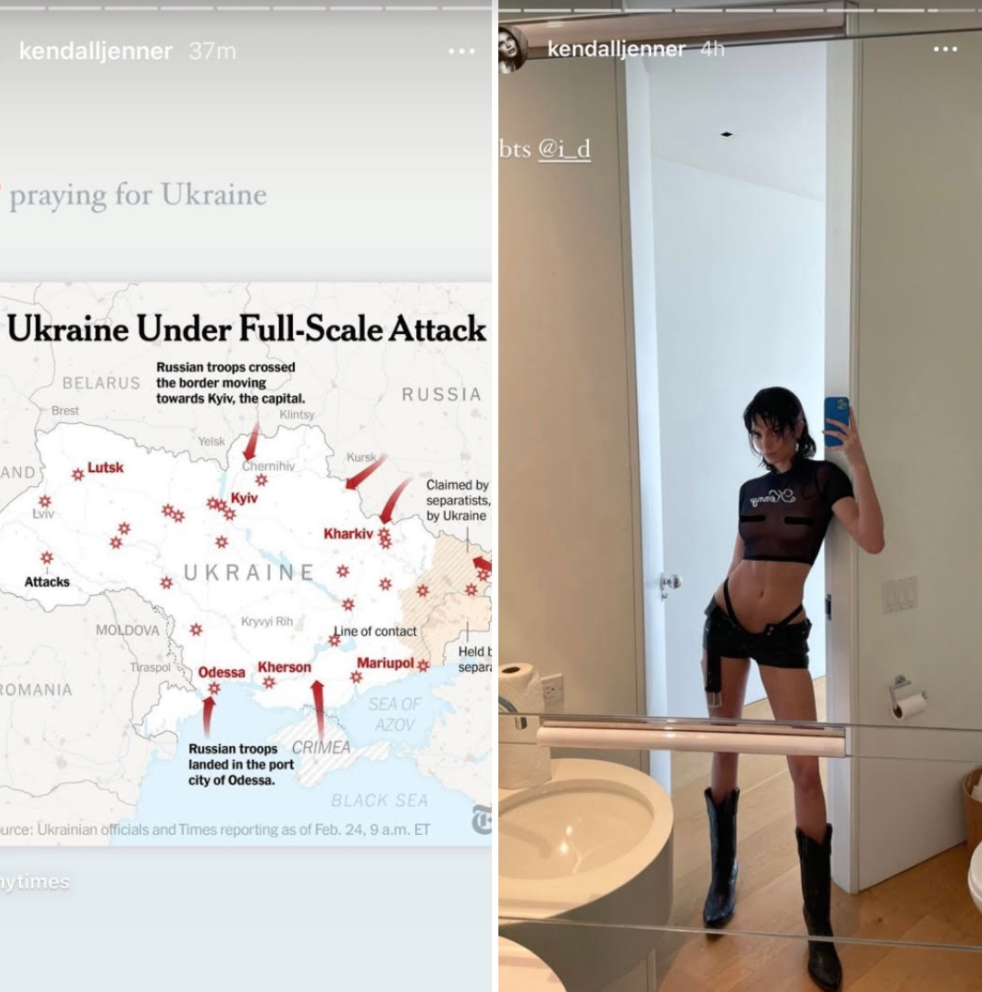

But it’s obvious that what no one considered when creating these social media platforms was how it would condition people to act. Acting being a skill we’ve all learned to hone in a climate that expects us to be a certain way and say the “correct” things—social media very obviously being a product of many predictions George Orwell made in 1984. Witnessing a full-scale war like the one currently being waged by Russia against Ukraine falls under that category of “how to act.” One Americans and Europeans (each sect being the most social media-centric of the West) alike were given some “precursor training” to in 2020, when the major cataclysms of a pandemic and racial injustice were brought to a glaring forefront that made it more “challenging” (read: less “in good taste”) to post selfies, belfies or pictures of food with the hashtag #foodporn. That is, it made it more challenging for those with even a vague conscience. For, how can any of us really be “happy” when we see so many others suffering? But human nature is set up to cushion us from being “weighed down” for too long by such guilt. Otherwise, we likely wouldn’t be able to function at all. Instead, we cope with memes in the age of social media. Memes that minimize, deflect and, in a full-scale war like this, ultimately demean.

And so, the question, increasingly, as we start to witness more destruction and catastrophe while in the age of social media, seems to be: is this okay? Am I allowed to still act “happy” on these apps when people are being bombed at the hands of a madman? Or am I “obligated” to feign something like “caring” each day in lieu of my regularly scheduled narcissism? You know, the way people did with that black square on Instagram back in 2020. The token gesture “given” to Black people’s trauma in the wake of George Floyd.

What’s more, Americans appear very content to pick and choose which countries or groups of people they’ll opt to send their “thoughts and prayers” to—for God or whoever knows that nobody gets that up in arms when the Israelis bomb and oppress Palestinians. That’s too much of a political hot potato to touch, what with the American alliance with Israel being so “key” to not pulling at a thread within the fabric of the world’s delicate consortium of “Good Guy” countries. Whereas Russia has been the “Bad Guy” since seemingly forever in the eyes of the U.S. Side note: nobody ever gives a fuck about what’s going on in Africa unless there’s warning of some contagion on the loose.

So we keep posting, acting “naturally.” Life goes on, and all that rot. And why should those of us who do have a chance to be “happy” and “carefree” be bogged down by the miseries of others? Well, because, at any given shift of the pendulum, that misery could be America’s. And when that time comes, the U.S. might have difficulty gathering much sympathy from others (particularly when they become among the first to suffer being climate refugees). The very ones it turned its back on.

As Russia’s actions are being branded as the start of WWIII (a phrase that has been bandied a few times in the twenty-first century), it makes one think of how people actually were during WWII. Not how they acted, but how they were. Their sorrows more genuine and less contrived because sadness wasn’t yet “presented” (read: posted) with the knowledge that it would be for public consumption as well. Can one really imagine somebody back then posting from the frontlines, “Just killed a Nazi lol!” Or a wife waiting for her husband to come back from war posting a nude on Insta to let him see what he was missing. It’s unfathomable. As opposed to now, when everything is documented all the time, rendering images and videos somewhat meaningless among the overall hodgepodge of horror. And maybe that’s part of why social media has achieved the larger aim of governments to desensitize its citizens from the lives that they unnecessarily ruin through war.

“Life is divided up into the horrible and the miserable,” Woody Allen once said (and he should know, having inflicted so much misery). His character in Annie Hall, Alvy Singer, continues, “The horrible would be like terminal cases, you know? And blind people, crippled… I don’t know how they get through life. It’s amazing to me. You know, and the miserable is everyone else.” The ones on social media observing the horrible and lightly commenting on it. “So when you go through life, you should be thankful that you’re miserable.” And that you have social media to reframe yourself as though you’re not. And as though nothing too terrible is happening elsewhere to the point where you would actually have to stop your quotidian postings and be “forced” by the dictates of politesse to acknowledge it.