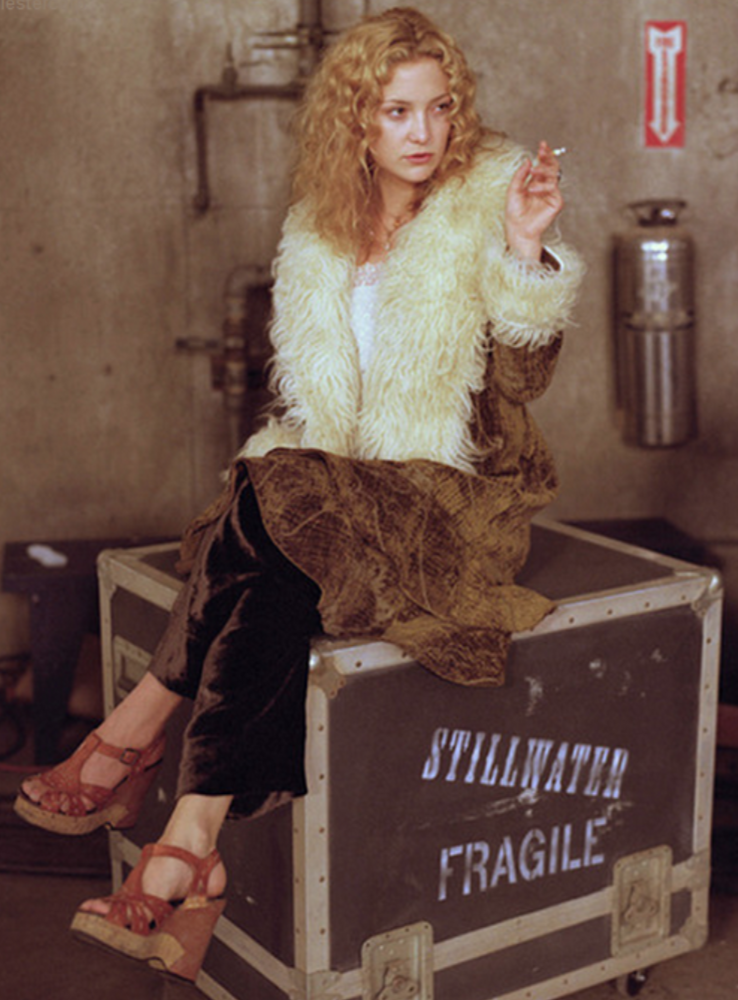

In 2000, when Harvey Weinstein was still experiencing his raping and pillaging glory days, it was, in all honesty, almost impossible to think of a movie with a positive feminine portrayal (we certainly can’t count Miss Congeniality or American Psycho). And yet, a film about the misogynistic music industry of the 1970s called Almost Famous managed to showcase, in its own subtle way, a woman free from the bounds of a man’s control. Maybe this is why the film fell short of box office success while still gaining enough critical accolades to make the cut for awards season. It was too “niche” to observe the lifestyle not of William Miller (Patrick Fugit), the hero of the story, but that of Penny Lane (Kate Hudson), a free-loving and free-wheeling “Band-Aid” who does what she wants when she wants, following the music (and the associated dick that comes with it) wherever it takes her.

While, of course, there are those narrow-minded feminists who would maintain that any woman who is so shamelessly imprisoned by penis could never truly be liberated, it is precisely because of being so, shall we say, humanitarian with her sexuality that Penny Lane is an inspiration on how a girl can live her best life. Even though her unfortunate and naive in its hopefulness attachment to guitarist Russell Hammond (real life scoundrel Billy Crudup) steers her down some frightening twists and turns on her ultimate path to emotional immunity, Penny is always one thing and one thing only: herself. Even if it’s a self slightly younger than she’s been letting on, using eighteen as her stock age when, of course, she’s sixteen. Which is still no match for William’s true age of fifteen (a shocking revelation that comes to Russell when his overbearing mother, Elaine [Frances McDormand, looking kind of like a MILF in this part], mentions this information in passing on the telephone).

It is perhaps his youthful purity that both draws and repels Penny to and from him–for she would never see him as fucking material more than friend material. And a girl needs a friend when she’s prone to the theatrics of overdosing on Quaaludes and demanding philosophically, “Where are all my friends?” Those friends would be fellow Band-Aids, Polexia (Anna Paquin), Sapphire (Fairuza Balk) and Estrella (Bijou Phillips). Women she’s displayed her best counsel and tutelage to in terms of accenting how to be a discreet, yet rock ‘n’ roll type of geisha (rock ‘n’ roll, in this case, signifying the prehistoric term before punk rock to denote being anti-establishment).

Her nurturing side is best wielded in the calling of groupie, serving not just as a muse and sexual objet, but also a maternal figure to the girls around her. And, soon, to William, offering, “Call me if you need a rescue. We live in the same city.” William, feeling terminally uncool, returns, “I think I live in a different world.” Penny politely glosses over his self-deprecation by commenting, “Speaking of the world…I’ve made a decision. I’m gonna live in Morocco for one year. I need a new crowd.”

That she establishes her desire to flee the often confining and oppressive world of cock rock in the first act is telling that Penny knows her current talents are being squandered in a milieu that will forever view women as second-class citizens, servants to the so-called gods (remember that “I am a golden god!” scene?) and geniuses that all conveniently happen to be male.

Although she falls into the trap of believing that a man can be anything other than selfish, it is William who snaps her back sharply into reality after she tries to call him out on his blatant jealousy over her relationship by insisting, “Look, you should be happy for me. You don’t know what he says to me in private. Maybe it is love, as much as it can be for somebody–” William cuts her off abruptly to confess, “Who sold you to Humble Pie for thirty-five bucks and a case of beer?” At first, the sting of his words gets to her, the realization that she is just as disposable to Russell as he should be to her–and soon will be. And then, in one of Hudson’s best acting moments (which are few and far between, hence the existence of Fabletics), she laughs through her tears to ask, “What kind of beer?” It is a moment of sheer beauty, to see her apprehend that she must be on her own in order to experience the careless abandon she thought she had been all this time.

Of course, it takes a traumatic push for her to do what she already knew she would all along, but, nonetheless, it’s evident that Penny has surpassed the need for male validation by the end of the film, going her own way as she had always intended and leaving the more emotionally stunted men behind in what is now her past to sort their drama out for themselves. Because Penny is far too much of a free bird to bother with the whims of uomo any longer. So yes, if you do squint hard enough at the plot development and character arc of Penny, it can be said that even in the climate of a Weinstein-dominated Hollywood at the turn of the century, Cameron Crowe managed to sneak in, whether he meant to or not, a message of female empowerment.