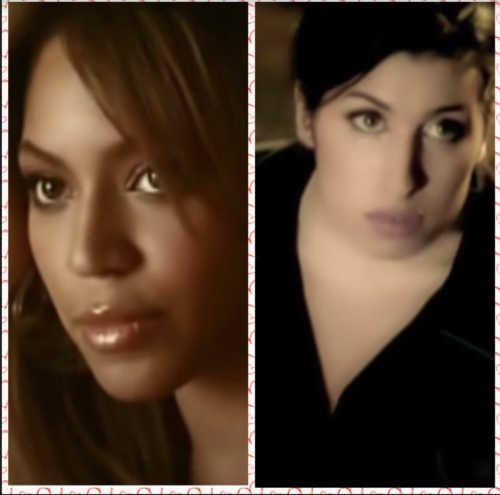

Before Beyoncé came along to claim Ne-Yo’s songwriting as her own on 2006’s “Irreplaceable,” Amy Winehouse was making a very similar (even if more “admitting to frailty”) statement on 2003’s “Take the Box.” Albeit in her own heart-on-her-sleeve way. For that was the Winehouse method—when it wasn’t adopting some Beyoncé-level braggadocio on the likes of “Rehab” or “I Heard Love Is Blind.”

And so, rather than transforming the sentiments behind a breakup into one of gratification and agency, Winehouse embraces the sadness behind the act of putting possessions into a box. An occurrence, truth be told, that might become less common as life becomes less tangible.

But in the 00s it was easy to envision the lament in the chorus, “The Moschino bra you bought me last Christmas/(Put it in the box, put it in the box)/Frank’s in there and I don’t care/(Put it in the box, put it in the box)/Just take it, take the box/Take the box.” In sharp tonal contrast to Beyoncé being très casual about the whole thing when she announces of a different box, “To the left, to the left/Everything you own in the box to the left,” Winehouse describes a scene of working-class mundanity in the intro to her own tale of woe. It’s here she paints the portrait, “Your neighbors were screaming/I don’t have a key for downstairs/So I punched all the buzzers/Hoping you wouldn’t be there.” But of course he was—why would Winehouse ever believe she could luck out?

Refusing to play it cool when she finds him still in the space, Wino croons, “Feel so fucking angry, don’t wanna be reminded of you/But when I left my shit in your kitchen/I said goodbye to your bedroom/It smelled of you.” Unlike Bey, who seems to be the owner of the house (and the name-checked Jaguar), therefore the one responsible for kicking the man in question out, Winehouse is forced into being the belittled party returning to scene of the crime that has become ever loving this person at all.

Where Winehouse can no longer have attachments to the material possessions in the box because of the emotional weight they now hold, Beyoncé acts the callous part when she directs, “In the closet, that’s my stuff/Yes, if I bought it, please don’t touch (don’t touch)/And keep talking that mess, that’s fine/But could you walk and talk at the same time?”

In contrast to Winehouse, she is level-headed and unemotional, more sentimental about the things she might lose to her ex’s rage and sense of entitlement as he packs his own items to leave than she is about the loss of the relationship itself. However, there is a moment when it becomes apparent that Bey’s confidence is all an act to conceal the true pain she’s feeling. This much is manifested in the bridge, “So since I’m not your everything/How about I’ll be nothing/Nothing at all to you/Baby, I won’t shed a tear for you/I won’t lose a wink of sleep/‘Cause the truth of the matter is/Replacing you was so easy.”

The video for the song would indicate otherwise as it takes quite a bit of primping and randomly playing in a band with her “girls” before Beyoncé manages to get a new “piece” to come to her door at the very end—the implication being that acting as a sugar mama to these men is what ultimately makes them as disposable as the literal objects she prefers to maintain.

This being in direct opposition to Winehouse urging her ex (pointedly not on aesthetic par with Wino in the video) to just “take the box” so she doesn’t have to be reminded of him anymore. While the messages of each song might vary in their approach to coping with the unexpected (yet written on the wall) demise of a relationship, both singles offer memorable imagery involving their respective boxes (take that as an innuendo if you choose).