Here and there, one notices a re-commitment to the film soundtrack that was once a constant. But with the decline of cinema as an “event” as opposed to something to stream any old time, it seems that the once tried-and-true “song created for a movie soundtrack” has generally fallen out of favor. With the sole film franchise keeping the tradition afloat whenever it hasn’t been chic being James Bond. And surprisingly, Taylor Swift was never asked to compose a track for any of those movies. Perhaps she’s just too American despite her overt fetish for Brits.

No matter, in the end, for all along, she was destined to put her soundtrack songwriting energies into Where the Crawdads Sing. Herself a Southern belle, it’s only natural that she should gravitate to the story of “marsh girl” Kya Clarke. Delia Owens’ debut novel didn’t take long for Reese Witherspoon to glom onto, and once that happens, it doesn’t take much time for a fellow blonde Southerner like Swift to follow. Or very long for Witherspoon to rally for a screen adaptation. Which Swift was evidently made aware of soon enough to decide to work on hand-crafting the song—truly tailoring it (fine, Tayloring it)—for the narrative during her folklore recording period. So yes, that’s exactly why it sounds plucked from that era, which also includes folklore’s “sister album,” evermore. Shooting her shot once again at being a more “in the mainstream” answer to Lana Del Rey, it bears noting that the latter has always been gung-ho about working on soundtracks. Mainly because her baroque pop stylings (e.g. “Young and Beautiful” for The Great Gatsby) have long been deemed ideal for any cinematic universe. She can even dig up songs from the vault (as Taylor likes to do) to provide a sonic mood when the time calls for it—just as she did with “Elvis” for the 2017 documentary The King.

But, by and large, musicians coming up with music and lyrics for a specific film is something that is so rarely done anymore. Certainly not in the spirit of songs like Simon and Garfunkel’s “Mrs. Robinson” for The Graduate, Blondie’s “Call Me” for American Gigolo, Madonna’s “Live to Tell” for At Close Range (or “This Used to Be My Playground” for A League of Their Own), Alanis Morissette’s “Uninvited” for City of Angels or Destiny’s Child’s “Independent Women, Pt. 1” for Charlie’s Angels.

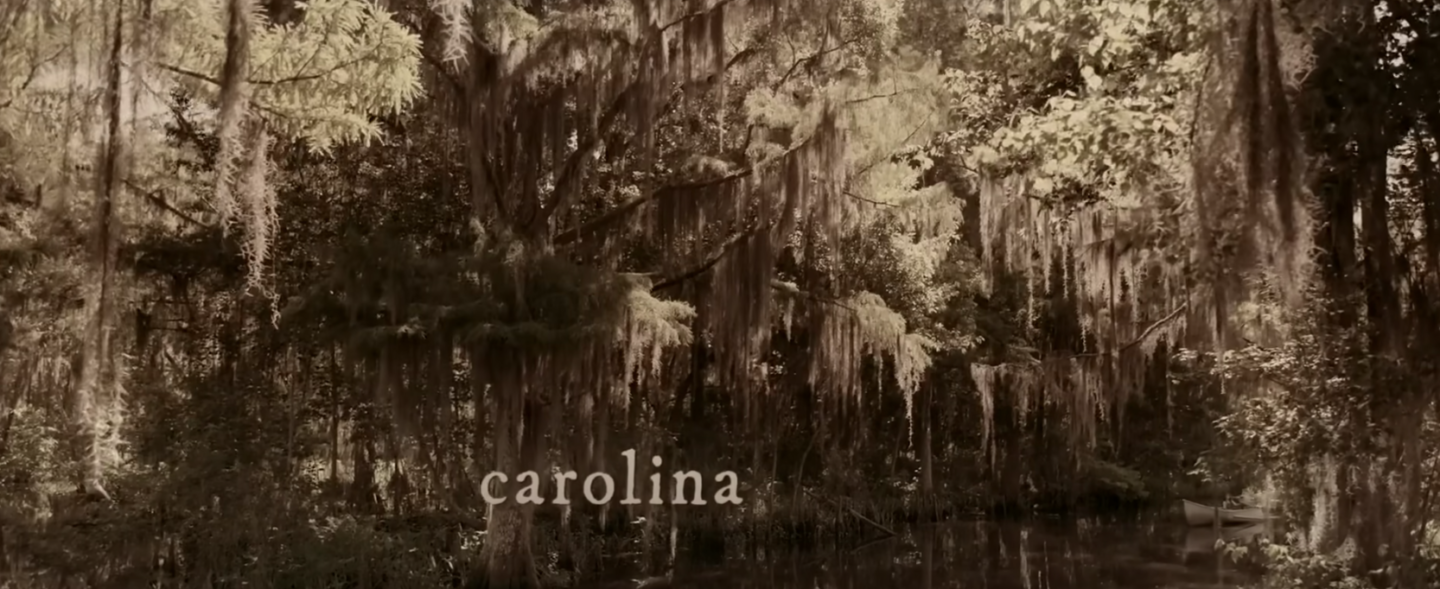

Swift appears to want nothing more than to remedy that situation. And while “Carolina” is not power ballad-y enough to find itself joining the annals of Whitney’s “I Will Always Love You” or Celine’s “My Heart Will Go On” territory, it is, at the bare minimum, sure to join Adele’s “Skyfall” and Billie Eilish’s “No Time to Die” (again, Bond has kept movie soundtracks afloat) as an instant modern classic. What’s more, like the aforementioned iconic power ballads designed expressly to mirror the sentiments of the main plotlines in The Bodyguard and Titanic, respectively, “Carolina” conveys the exact mood of Where the Crawdads Sing, too. A universe in which Kya (Daisy Edgar-Jones) is persecuted and ostracized at a time when that was particularly hype in America: the 50s and 60s (which means the 1800s in Southern perspective).

Being that the story’s time period is as important to it as the location, Swift took care to only use string instruments that were in existence before 1953, lending it an even more “uncomplicated,” “rough-hewn” sound than Swift’s usual fare. And so it is that, with the use of mandolins and fiddles, the “Appalachian folk song” comes to fruition—Swift-style. And who should know better about “dat Appalachian life” than Miss Tennessee-by-way-of-Pennsylvania herself (that is, when she’s not betraying her brethren by being a Yankee in New York Shitty)?

Opening with a breathy, “Oh, Carolina creeks running through my veins/Lost I was born, lonesome I came/Lonesome I’ll always stay,” Swift reels us in like a goddamn crawdad. Speaking from Kya’s point of view, it’s as though Swift could have created the character herself within the folklore/evermore worlds (see also: her Betty/Inez/James love triangle). Especially being as nature-oriented/cottagecore as those realms are.

The sort of “wild” that prompts Swift to say, “Carolina knows why, for years, I roam/Free as these birds, light as whispers/Carolina knows.” The drama in Swift’s voice increases for the pre-chorus when she announces in an almost accusing manner, “And you didn’t see me here/No, they never did see me here.” That can obviously refer to a figurative sense as well—for “civilized” folk never really see those who live on the fringe.

Going for more Del Reyian flair in her descriptiveness, Swift paints the detailed picture, “Into the mist, into the clouds/Don’t leave/I make a fist, I’ll make it count/And there are places I will never, ever go,” adding, “Carolina stains on the dress she left/Indelible scars, pivotal marks/Blue as the life she fled Carolina pines, won’t you cover me?/Hide me like robes down the back road/Muddy these webs we weave.” Using the Swift signature of talking about marks and stains (she would actually make a really good Lady Macbeth in the future), she also incorporates the use of LDR’s favorite couleur to name-check.

The sustained portentousness of the song is compounded by Swift conveying the idea that she shares a secret with the Tar Heel State that only it can ever know. Thus, she concludes, “Oh, Carolina knows why for years they’ve said/That I was guilty as sin and sleep in a liar’s bed/But the sleep comes fast and I’ll meet no ghosts/It’s between me, the sand and the sea/Carolina knows.” Going back to the aforementioned “Uninvited,” “Carolina,” possesses its own similarly haunting quality. In addition to being one of the most standout singles of late to honor the great tradition of songs made specifically for movies.