In 1961, there wasn’t much in the way of excitement on Long Island (there still isn’t really). For ten-year-old Alice Bloom (Eliza Dushku, in her debut role), the only bright spot, let alone a source of entertainment, is seventeen-year-old Sheryl O’Connor (Juliette Lewis) who lives across the street. In Alice’s eyes, she’s the most glamorous creature that ever lived, prompting her to go so far as to wear the same perfume (Ambush) and listen to the same record (“Ruler of My Heart”–the Lisa Fischer as opposed to Irma Thomas version) as her idol, just to feel even remotely close to the only person in the neighborhood that she has a connection to. “If I could just be her for one night, even for just one minute…” Alice wishes as she stares out her window at a half-dressed Sheryl. It’s not as lesbianic or Single White Female as it sounds. Alice is simply a girl who sees Sheryl as someone truly having it all, not just the attention of boys, but the attention of her own father–something Alice is sorely lacking in her life from her less effusive patriarch, Larry (John Dossett), particularly in the wake of her mother, Carol (J. Smith-Cameron), losing another baby and the pressure Larry puts on her to squeeze out a new “product.” Ideally a boy.

Of course, Sheryl isn’t quite as invested in the “friendship” until Alice happens to serve a useful purpose to her. As Craig Bolotin’s directorial debut (after catching a screenwriting break circa 1985 when he gave some uncredited rewrites to the script for Desperately Seeking Susan), the careful weaving of Alice McDermott’s original Pulitzer-winning novel of the same name is handled with a deftness that only a writer-director can implement. Including the complexity of Sheryl, at first perceived as some sort of Catholic “good girl” a.k.a. a tease. However, it’s clear that she might actually be willing to give some of these boys more affection if she wasn’t so vexed by them. Like one ogler who insists, “Come on sweetheart, your Romeo’s arrived,” as he harasses her at the bowling alley while she rings the bell at the desk ad nauseam to get some shoes. But it isn’t to be this boy who is her Romeo so much as the one who pops out from behind the desk, Rick (C. Thomas Howell). As their eyes meet and the attraction is immediately evident, he soon asks, “Do you believe in love at first sight?” She slowly responds, “No.” “Me neither,” he smiles back. Naturally, they both know that this is precisely what has just occurred between them. And so, too, does Alice, always lurking and watching from afar.

If she thought that monitoring Sheryl was scintillating, she just about loses her damn mind when suddenly there’s a romance between her and Rick to track as well. One that only blossoms and solidifies when Sheryl is informed of her father’s death the very same day she meets Rick. Indeed, there is something highly Electra complex-oriented about the timing. As though Sheryl needs to fill the void with a dominant male presence instantaneously. A new “ruler” of her heart, as it were.

So it is that several weeks after sharing a kiss on the day of her father’s funeral, Rick finally shows up to her house to take her out somewhere. And not a moment too soon, for as Sheryl tells her mother of being stuck at home, “I can’t breathe in there.” And they’re off, with Rick already garnering the disapproving looks from both Sheryl’s mom and Larry across the street, who seems to have just as little abashment about watching Sheryl as his daughter. He is, through and through, the no-good Romeo for their suburban Juliet. Likely all the more reason why Sheryl falls for him, being so bold as to kiss him across the red and white checkered tablecloth at the oceanfront seafood joint he’s brought her to. Somewhat shocked by her forwardness, he states, “I thought you went to Catholic school.” She shrugs, “Yeah, but they’ve but telling us about guys like you since I was in the first grade… I don’t wanna say anything but do the girls in Queens actually fall for this kinda routine?” Feigning innocence, he inquires, “What routine?” She grins, “You know, stuffing me with oysters and tequila. You got your hair trimmed. You got on Aqua Velva.” He refutes, “It’s not Aqua Velva.” Sheryl smiles. “Well it’s too bad. It’s my favorite scent.” Probably because her dad wore it, seems to be the unspoken implication.

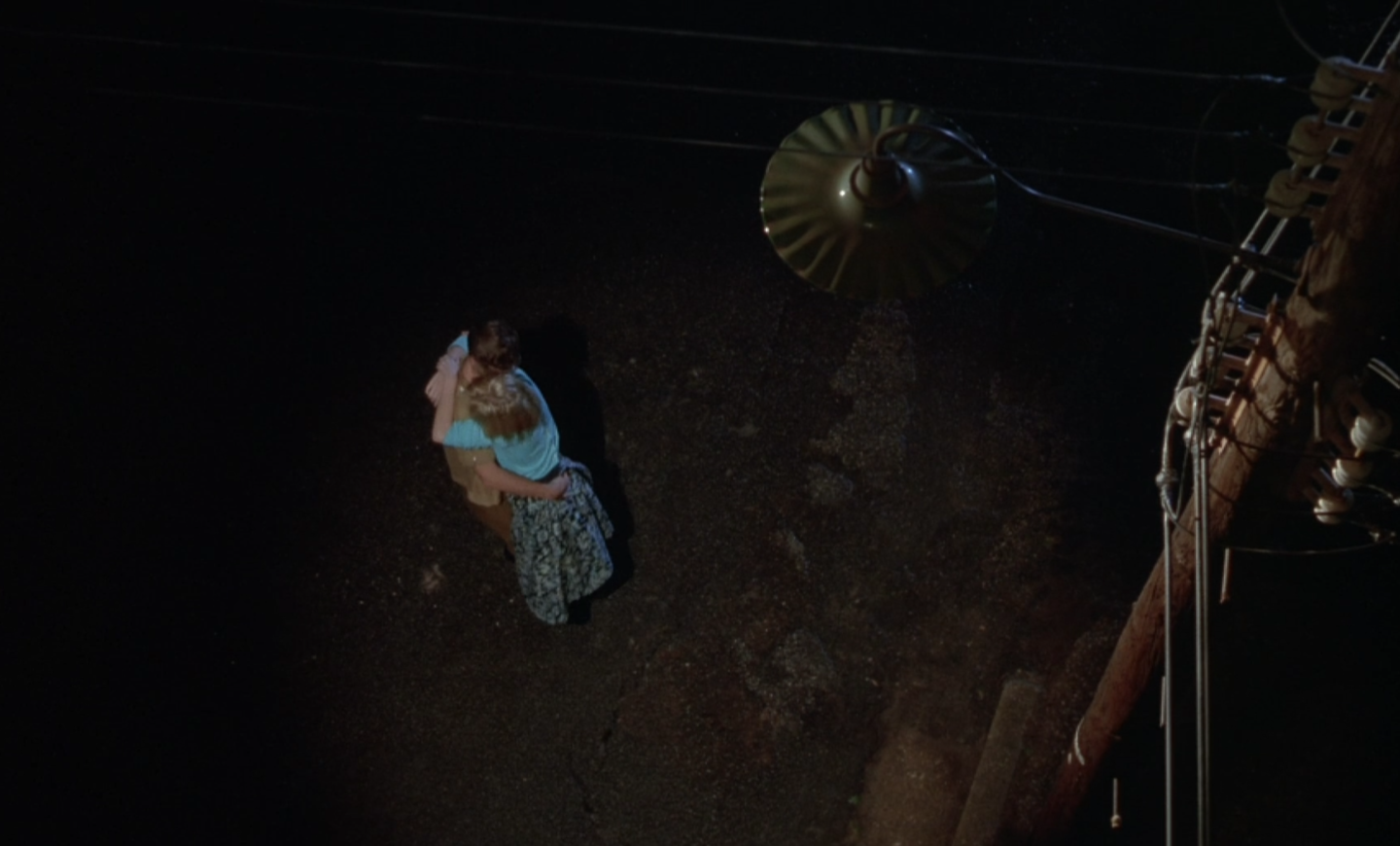

As their romance heats up, so does the secrecy it is shrouded in, with Rick sneaking Sheryl back late at night and dancing in the street with her before letting her return to her Juliet-like room, where she so often peers out as though poised to say in a Long Island lilt, “O Rick, Rick, wherefore art thou Rick?” Alas, it’s one public display in daylight that incites Larry to yell at Sheryl’s mother about our doomed loverboy, soon after to be banned from seeing his beloved.

In the meantime, Alice struggles to understand why no one except Rick and Sheryl seem to comprehend what love is, as they are the only visibly passionate ones around her. Asking her mother the question of if she really loves her father then, “How come you and dad never kiss like Sheryl and Rick?” Carol, uncomfortable with the query, offers, “Well, we did. It’s just, um, we used to… but it’s different now. It changes.” Upset by the notion, Alice demands, “Why?” Sounding like Ally Sheedy in The Breakfast Club with the classic line, “When you grow up, your heart dies,” Carol laments, “You just get older, that’s all. You just get older.” Yet for Alice, the idea of Sheryl and Rick ever ceasing to love one another is unfathomable regardless of how old they get. That’s the greatest strength and Achilles’ heel of the young–they can never imagine “true” love drying up and fizzling out. As it probably would have if Romeo and Juliet had been able to date a couple more years.

Unfortunately, things are about to take a very Molly Ringwald in For Keeps turn, with Sheryl shipped off to what amounts to a convent after her mother asseverates that if she really loves Rick, she won’t tell him about being pregnant. It all has a very working class, Long Island in the 60s feel (granted, the book was released in ‘87 and the film in ‘92). With the drama and fatalism to match Shakespeare’s thanks to anything involving Italian-American milieus with a staunchly Catholic backbone. The question is, will Alice’s belief in true love win out over the pragmatism that comes with “maturity,” ergo jadedness? Or will she fall prey to watching yet another pair of star-crossed lovers go astray?