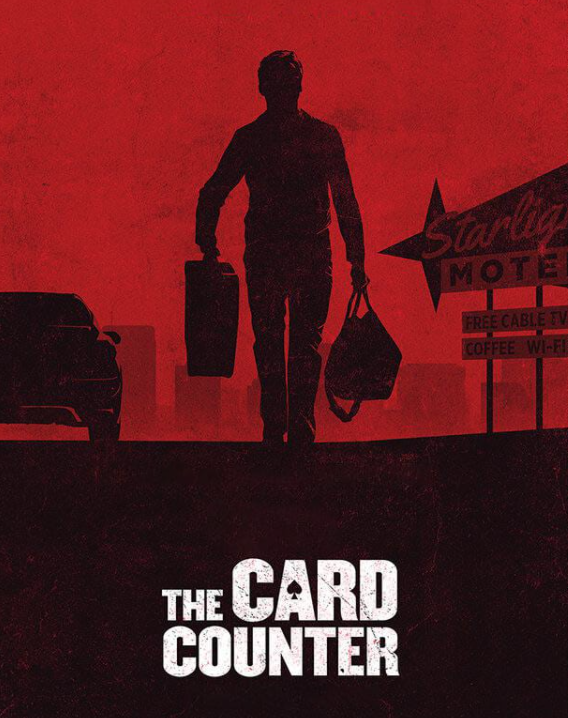

The thing one can immediately observe about Paul Schrader’s visual style in The Card Counter is that he wants you to notice how shitty America is. An aesthetic mirror of its values. He wants you to see what the soldiers of America’s various defense outlets are really protecting. Which is to say, a lot of fucking strip malls and decay. He does his absolute damnedest to make sure that his viewers see it, with shots held on horrifically-named chains like Chat n’ Chew, pathetic kidney-shaped pools at seedy motels located off the side of a main road. The type of motel where PFC William Tillich a.k.a. “William Tell” (Oscar Isaac, looking a little more like Andy Garcia all the time) so often stays in his line of work as a professional gambler. But, more to the point, he’s a card counter (in case the title didn’t give that away). A skill he picked up during his eight years spent in a military prison.

We aren’t made privy to just why William was serving out a sentence until his path crosses with Kirk with a “C” a.k.a. Cirk (Tye Sheridan, the new Miles Teller meets Shia LaBeouf). The two encounter one another at a presentation being given by Major John Gordo (Willem Defoe), whose name on a poster in a hotel catches William’s eye. Cirk seems to recognize William the second he sits down. Being more than a little creeped out by this, William starts to leave, only for Cirk to thrust a piece of paper at him with his contact info. Info that William will eventually use to get in touch because his curiosity gets the better of him.

Although William is technically out of prison, he still lives as though he’s in it, devoted to an ascetic routine that includes journaling, and waiting. All in hotels that he covers the room furniture with in plain sheets secured with twine. It’s more than a little eccentric, a little OCD (but also seems like good sense in the time of corona). It’s as though William has an obsession with blotting things out to sustain an illusion of being “clean,” “pure.” But deep down, we can see he doesn’t feel that way at all. Schrader wants us to ask the question, “What could he have done that he can’t forgive himself for?” This is where he came up with the notion of making Abu Ghraib a central fixture of the narrative, commenting, “Even serial killers and Ponzi-scheme guys have justifications. Then I thought of Abu Ghraib—to besmirch the image of your nation. You’ll die and everyone else will die, and that stain will remain. There’s nothing you can do about it; it will always be a stain on your country and you put it there.”

It seems all-too-timely that, just as The Card Counter comes out, so, too, does an article called “I’ve been held at Guantánamo for 20 years without trial. Mr Biden, please set me free.” In it, a man named Khalid Qasim details the types of horrors he has endured since 2002 at the hands of soldiers like the one William is based on. And yet, these are men who go by the orders of their superiors (e.g. Major Gordo), in turn, going by the orders of the U.S. government, specifically the office of the highest level. Yet these aren’t the ones being punished, or claiming any responsibility whatsoever. It’s instead men like William, who serve as the fall guy. A convenient scapegoat to placate too many people from calling bullshit on America and its supposed “way of life.” Which, ultimately, is to suppress and subjugate with just as much brutality as any totalitarian regime.

This is what Cirk can’t forgive, as his own father ended up killing himself as a result of the guilt of what he did to those detained at Guantánamo. And why he has devoted his own life to the pursuit of vengeance, specifically seeking to take out Gordo. When he encounters William, he views it as providence. Ironically, William has a tattoo on his back that reads: “I trust my life to Providence I trust my soul to Grace.” He probably got that before Guantánamo. With William having the most motive to take revenge, Cirk feels he can convince him to join forces in order to torture Gordo and give him a taste of his own medicine. William, instead, invites Cirk to join him on his tour of various casinos throughout America. Because, upon learning of Cirk’s debts, he decides to take an interested financial backer, La Linda (Tiffany Haddish), up on her offer to support him in higher-stakes games—even though this goes entirely against his principle of keeping a low profile by only pursuing modest winnings at every game. And yet, he sees Cirk as a chance for some form of absolution, a way to repent by helping him out and keeping him from trying to go forward with his cockamamie scheme to kill Gordo.

Incidentally, before Cirk’s father killed himself, he decided to take his rage over Guantánamo out on his wife by beating her. This prompts her to leave, which meant that only Cirk was left behind for him to abuse. Nonetheless, Cirk insists to William, “That’s in the past.” William rebuffs that concept with the platitude, “The body remembers, stores it all.” He would certainly know, having seen what he saw. Inflicted what he inflicted.

Despite his attempts to keep any form of a relationship at a distance, he finds himself getting closer to La Linda, who tells him, “You should do something else. Just for variety.” “I like playing cards,” he returns solemnly. The monotony is something he can both control and that he feels is a type of atonement. It also harkens back to the man alone in a room motif that Schrader has cultivated throughout his career. One that allows plenty of time for us to hear William’s voiceovers as he journals. As Schrader notes of this ongoing theme of isolation in his films, “The line that I wrote relatively unknowingly in Taxi Driver is one that comes back. Travis writes in his journal, ‘Every day is like the day before. The hours pass, the years pass. And then there is a change.’ I wrote that in 1972 and I’m still writing that.”

Of the rather singular genre Schrader has carved out for himself, he also remarks in an article for the Los Angeles Times, “I stumbled on it with Taxi Driver. It was transplanted from fiction; it really wasn’t a movie genre: the existential hero. It was out of European, twentieth century fiction—Dostoevksy, Sartre, Camus. I discovered it was something I was good at; it was natural to me and other people weren’t doing it.”

Schrader’s focus is also on “profession” here. On the boredom and ennui of making a living at gambling. As Schrader characterizes it, “You just sit there and life flows past you. It must be somebody who thinks this is a simulacrum for life itself.” Then again, that’s pretty much all work, regardless of industry.

At one point, it is asked, “So what’s your story? Everybody’s got a story.” It sounds almost like the man on the street in Pretty Woman saying, “What’s your dream? Everybody comes here; this is Hollywood, land of dreams.” But William only ended up in the land of nightmares by going to Guantánamo. And tormenting others physically has subsequently led to William being emotionally tormented himself. Nonstop—like a 24/7 slot machine.

Although the viewer might be suspicious of any kind of happy ending for a man like William—especially since Schrader is so like Camus—he surprises us with one small glimmer of hope, portrayed through a “The Creation of Adam”-like final scene. But the question remains: can someone with so much trauma and guilt ever really be revived or resuscitated anew? Or are they ultimately doomed to wander the planet spectrally until the end of their days?