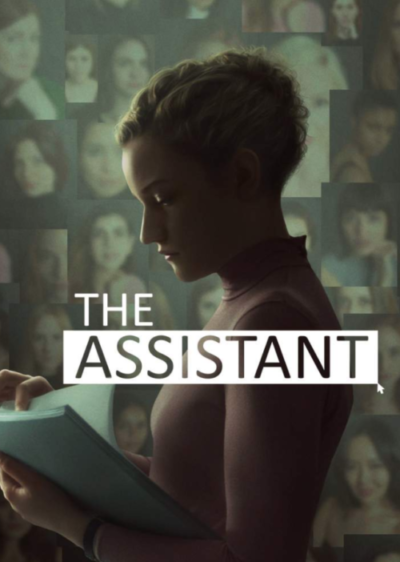

As Kitty Green’s debut feature (after releasing three documentaries, including Casting JonBenét), The Assistant feels like a petri dish of a sociological study on the effects of male-dominated office culture. Particularly upon a female film aspirant slowly coming to terms with the fact that all the rumors about the seedy underbelly of the film industry turned out to be true. Using her documentarian eye, the movie does often come across as having that gritty, hyper-real quality, thanks to both the subject matter and the fact that the events of The Assistant take place entirely in one day–a very long day at that, made to feel even more protracted thanks to the emotional roller coaster we’re also on with our protagonist, Jane (Julia Garner).

Her name alone, instantly conjuring the “Plain Jane” mantra, seems like part of the reason her faceless boss–whom we never actually see, merely adding to the god-like status he holds within the company, and the industry–hired her. Looking for someone mutable and malleable. Eager to please as a result of her mousiness. But Julia has something else many assistants don’t: a brain. More than just a pretty face, she graduated from Northwestern with aims of becoming a producer. Being hired at this particular production company, as everyone assures her, will put her on the fast-track toward that goal. She starts to understand that it’s also putting her on the fast-track to aging prematurely as she adheres to the “first one in, last one to leave” philosophy that’s expected of assistants with a plucky, youthful nature. The very kind men like her boss know they can capitalize on to milk as much out of her as possible for the least amount of money–and the most emotional fallout.

Jane has been compliant and cooperative up to now, it appears, but that resolve is obviously slipping, as we see on this particular morning that we watch her get in a car (one of the company perks keeping her holding on to the job) at the crack of dawn to head to the SoHo area where the office is located and go about the preparations of getting the office in order–existing in a calm before the storm as she makes coffee, tidies up and squeezes in just enough time to chug some Fruit Loops (indeed, Green makes it very clear that there’s hardly ever a spare moment to be found in order to eat properly, hence Jane getting embarrassingly caught with a leftover pastry in her mouth as she’s picking up in a conference room after a meeting).

The frequently close-up shots of Jane when she’s on the phone lend added intensity to the stress of a job with so many unspoken descriptions upon being hired that Jane must learn as she goes along–otherwise risk being replaced by one of the many waiting in line to take her place. Among such tacit expectations of her role is lying to her boss’ wife whenever she calls to angrily demand his whereabouts.

But how could she have truly known this was what was to be expected? So much of the film industry, particularly in the years of “Golden” Hollywood (as Ryan Murphy’s recent Hollywood iterates) and, subsequently, the era that saw Harvey Weinstein’s rise to dominance, is like a meat factory. Everyone wants the meat (i.e. movies and entertainment), but no one wants to know what goes on behind the scenes in order to make it all happen. Because if we did, “consumption” would be made extremely difficult without constantly thinking about it. Yet, at the same time, even though we know, and people like Jane know, they are too often conditioned to turn a blind eye in order to let evil flourish and iniquitous practices shine. It’s what’s best for “production,” after all. And yet, it’s as Einstein said, “The world is a dangerous place, not because of those who do evil, but because of those who look on and do nothing.” For so long, this was Hollywood, and the long (dick-shaped) arm that extended all the way to New York to make sexual abuse–and abuse of every kind, for that matter–tolerated on each geographical side. The world rendered a playground of acceptance and complicity for this “boys’ club” behavior.

When Jane tries to actually say something, to speak on a strange occurrence that she knows carries the weight of power abuse even if a seemingly “small” incident, she is met with the approach of a gaslighter in HR’s Wilcock (Matthew Macfadyen)–a fitting moniker for the misogyny that abounds in the dominion he reigns over. Indeed, someone in his position could have changed the trajectory of accepted sexual assault so much sooner were it not ingrained to protect the “leader” at all costs. The ringleader of the torturers, to be more specific. When he spells out for Jane that she’s essentially acting like a ridiculous little girl, she rescinds her complaint, walking out the door to be further condescendingly told, “I wouldn’t worry too much. You’re not his type.”

Lingering in the background of it all is the slipping away of Jane’s personal life, as she starts to lose touch with the real world outside her office. So tied up in her work, she’s even forgotten to call her father on his birthday, as her mother reminds her the next day when she calls. Feeling like the ground beneath her is quicksand, like everything is bottoming out, Jane’s endless day is concluded with a ride down in the elevator with two of her boss’ higher-up associates, about to accompany him on a trip to Los Angeles. It is the female of the two who tries to cheer Jane up with, “Trust me, she’ll get more out of it than he will.” This, to be sure, is one of the worst things of all, to realize that women in the business are often the most misogynistic of anyone.

So it is that they leave the new “assistant” alone with him while they wait downstairs. Jane, meanwhile, goes to a market across the street to buy a muffin, finally allowed to eat without interruption. Finally getting a chance to speak with her father on the phone, who still radiates an aura of wholesomeness (talking about taking the dog out for a walk and such) that now sounds foreign and remote to her, she watches the light in the office remain on. While the one inside her is clearly starting to dim.