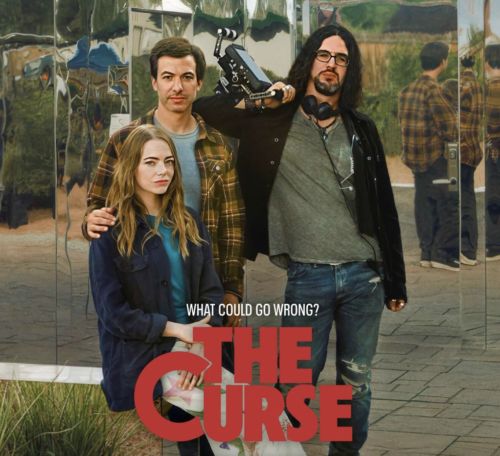

Consistently talked about as the weirdest, most unclassifiable thing that has ever aired on television (obviously, those who say that have never seen Twin Peaks), The Curse’s series finale left viewers feeling more unsettled than ever. And, to be sure, it was probably one of the strangest, most unpredictable conclusions of a TV show in the medium’s history. But that’s what one should have expected from the likes of Benny Safdie (whose brother, Josh, acted as one of the co-producers). And yes, one supposes, “oddball” Nathan Fielder. An “actor” whose inherently annoying personality translates easily to the role of Asher Siegel, the playing-second-fiddle husband of Whitney Siegel (Emma Stone). Formerly Whitney Rhodes, her maiden name before she likely married Asher to free herself of it, thereby freeing herself of ties to her parents, Elizabeth (Constance Shulman) and Paul (Corbin Bernsen), who are notorious throughout Santa Fe for being slumlords.

As Whitney has been trying to cultivate a “different” kind of real estate brand (while still using her parents’ blood money to do so), Asher has been her devoted minion in helping her achieve that goal. Even if she doesn’t seem to fully realize he’s guilty of having skeletons in his own faux-noble closet. In fact, it doesn’t take a psychologist to comprehend that Whitney has sought out her parents in Asher’s form. Especially, as we learn during the first episode, “Land of Enchantment,” in terms of Asher’s micropenis. A trait that her father also shares with him—and has no problem discussing with Asher when the couple comes over to visit. While pissing on his tomato plants to “nurture” the soil, he tells Asher, “Break the illusion in your mind. ‘Hey, I’m the guy with the small dick.’ I tell all my friends. They know.” Paul then adds, “Be the clown. It’s the most liberating thing in the world.” This little piece of advice foreshadows how Asher will soon be referred to as the “jester” to Whitney’s “queen.” Green queen, that is. A term Whitney comes up with as the name for the show in lieu of the mouthful that is Fliplanthropy.

The show’s producer, Dougie Schecter (Safdie), is all for the name change, assuring her that HGTV will love it. One of the final cuts of an episode he plays for Whitney, however, is not something they’re likely to “love.” Mainly because of how utterly banal and lacking in “tension” it is. Whitney, prepared to do whatever is necessary to ensure her show is a hit, decides to take Dougie’s advice and give voiceovers to certain “subtle” moments she shares with Asher that play up the reasons behind her vexed expressions. After all, as Dougie points out in episode six, “The Fire Burns On,” “Look, what we have here is a frictionless show. There’s no conflict, there’s no drama. And that’s not something people want to watch. And I get that you’re trying to kind of put this town out there, put it on the map and you can’t talk about any of the racial tensions, or the crime, stuff like that. So what’s left? You and Asher.” But there won’t be anything left of them if Dougie has his way about amplifying the drama and getting Whitney to commit to it. Which of course she does—because there’s nothing she wouldn’t do to ensure the “reality” show is a success. That word, “reality,” being, needless to say, a total fabrication that’s manipulated for the very specific purpose of “audience entertainment.” Because, as Dougie said, no one really wants to see unbridled reality. It’s, quite simply, too dull. And all a viewer ultimately wants out of any show, no matter the genre, is to be taken out of their own lives for a while.

This has become more and more the case as the TV-guzzling masses seek to distract themselves from the horrors splashed all over the news like pure entertainment itself. But for those who would rather see chaos that has more of a “narrative”—while also seeking to believe they can learn something about “helping the planet”—a series like Green Queen could certainly deliver on that dual level. Or so Dougie and Whitney want it to. Asher, on the other hand, is just a stooge who would like to believe he has any idea what’s going on. In the end, though, it’s apparent that he was always just a worker bee carrying out orders for his hive queen. Not green queen. And, talking of that color, it does apply to the general green-with-envy aura that both Asher and Whitney have (though more the former than the latter). They’re so concerned with their perception, after all, that it’s easy for them to become jealous of anyone who is perceived as more genuine (and actually is) than they are. The way local Native American artist Cara Durand (Nizhonniya Luxi Austin) is—not just for her art, but her entire “aura.” This is precisely why Whitney and Asher glom onto her like leeches as they parade her artwork in their passive home. As though owning one of her pieces makes them as “brilliant” by proxy.

Throughout The Curse, Whitney and Asher do their best to convince the rest of the town (and, hopefully, the rest of America) that they are as beneficent as someone like Cara. Though, naturally, a show like The Curse presents the more recurrent dilemma regarding white people of late: can any white person really be “good” no matter how hard they try if their inherent privilege is at the root of most of the world’s suffering since the beginning of civilization? What’s more, is there really any “goodness” at all in a person when their motives are always grounded in self-aggrandizement. As Joey Tribbiani (Matt LeBlanc) on Friends (the whitest show you know) put it, “Look, there’s no unselfish good deeds, sorry.” Because the vast majority of them serve, in some way, to make the “do-gooder” feel better about themselves. To boost that person’s own ego.

With the white ego being rattled more and more every day (resulting in the current neo-Nazi political response), there’s been an according uptick in over-the-top displays of “concern” and “allyship.” For the last thing most white people (save for the MAGA ilk) want to be accused of is villainy. And what’s the easiest way for a blanco to boost their “goodness” cachet? The eco-friendly trend. Which is, in fact, a trend rather than a genuine way of life that anyone wants to endure long-term. But so long as Whitney and Asher can cursorily (no “curse” allusion intended) parade how great they are for making “real change” in the community and, therefore, the world, they don’t have to feel too guilty when they do totally hypocritical things like put an air conditioner in the passive house (that’s supposed to naturally moderate its temperature “like a thermos”) they live in.

As the couple goes about the process of filming their episodes centered on selling Whitney’s “passive” (and cartoonishly mirrored) homes in the little-known (though not anymore) Española, a dark and ominous pall seems to be cast over everything. Or so Asher tells himself after being “cursed” by a little girl in a parking lot named Nala (Hikmah Warsame). At Dougie’s urging, Asher approaches her to buy one of the cans of soda she’s selling so Dougie can film him doing “good person” shit. Alas, Asher makes the mistake of handing her a hundred-dollar bill solely for the shot, then telling her he needs it back. Something to the effect of this exact scenario is what inspired the idea for The Curse in the first place, with Fielder recounting to IndieWire how “on a routine trip to pick up a new cell phone, [he] was stopped by a woman asking for spare change. He didn’t have any, told her as much and she responded by looking him straight in the eye and saying, ‘I curse you.’” Almost an exact replica of what goes on between Asher and Nala (minus the can of soda). And, just as it is in The Curse, in real life, “Fielder went on his way, but couldn’t stop thinking about the stranger’s sharp words. So he went to an ATM, got twenty dollars and handed it to her. Just like that, she lifted the curse. When Safdie heard the story, he asked Fielder, ‘What would’ve happened if you went back there and she wasn’t there? Then your whole life would be ruined because the curse would just be on you. It would be something that you had to think about forever, and you’d never know for sure whether or not something happened to you because of that or not.’” With both men so openly giving such credence to the woman’s words, well, talk about giving more people a reason to say “I curse you” as a means to extract money.

Yet Fielder insisted, “I don’t believe in that stuff, but I can’t get those things out of my head. Sometimes if someone says something to you, even conversationally, where you feel like you messed up something, it can linger in your mind and grow and consume you. Then we just started riffing on that idea, like, ‘Wouldn’t it be interesting if that vibe was hanging over an entire show?’” And there is a large element of The Curse that promotes the idea that if you put thoughts or intentions out into the world, they can have an eerie tendency to, ugh, manifest. That overly-used-by-white-people word. Particularly white people in L.A. But were it not for L.A. and its Lynchian vibe, it can be argued that Fielder and Safdie might never have created The Curse. For it began with Fielder riffing on “trying to encapsulate odd experiences I had since I moved here. L.A. sometimes feels like… there’s something off” (Mulholland Drive anyone?).

New Mexico stands in for that “off” feeling easily enough. Though one can imagine the passive living houses Whitney is trying to shill doing quite well on the real estate market in L.A. Where Whitney might also have been tied to her slumlord parents in one way or another. Though she is initially convinced, “There is nothing on Google that ties me to them,” she later demands of her father, “Why does the city keep calling me and telling me my phone number is associated with units in the Bookends?” Worse still, if she Googles “Whitney Rhodes,” there’s a picture of her standing next to her parents at a “ribbon cutting” for the Bookends Apartments. A detail that proves just how much harder is to live in denial about one’s self and one’s “goodness” in the modern age, where the internet never lets anyone forget all of the shady things they might have done in the past. In other words, to quote Dougie berating Asher, “Doesn’t this get exhausting? Cosplaying as a good man?”

The answer, for white people, is: never. What’s more, the sardonic irony of a phrase like “passive living” applies precisely to how most white people live/engage with the world. Nevertheless, we are all (regardless of color) living pretty goddamn passively as we watch the present destruction unfold around us. Because, in truth, none of us knows how to stop it. Or, more to the point, none of us knows how to truly and profoundly disengage with the behavior that capitalism has furnished and indoctrinated humanity with for centuries. To that point, The Curse is as scathing about faux beneficence as it is about the oxymoron that is “sustainable capitalism.”

As for whether or not Asher’s eventual fate at the end of the final episode was really a result of Nala’s “curse” or a phenomenon grounded in the “science” of the passive house causing a reverse polarity of gravity in Asher (episode two was, funnily enough, titled “Pressure’s Looking Good So Far”), that depends on the viewer’s interpretation. Though it’s pretty clear that Asher no longer gave weight (again, no pun intended) to the “curse” theory. A “theory,” quite honestly, that is peak white privilege in and of itself. Think about it: how white is it to assume a curse has really been put on you just because a few things don’t go your way (e.g., not getting any chicken in your chicken penne order)? Perhaps this is why Asher can at last admit to Whitney in the penultimate episode, “Young Hearts,” “I’m a terrible person, don’t you see? There’s not some curse. I am the problem.” Ah, that Swiftian admission. The one that white people, more and more, love to declare because, so long as you acknowledge what you are, you don’t actually have to do anything to change it.

Asher, however, vows to Whitney that he’s a changed man at the end of “Young Hearts,” assuring, “If you didn’t wanna be with me, and I actually truly felt that, I’d be gone. You wouldn’t have to say it. I would feel it and I would disappear.” To many, that seems like the obvious foreshadowing to what becomes of him in the finale. But there was foreshadowing long before that at the end of episode five, “It’s A Good Day,” when Asher and Whitney are shown going to bed together only for the scene to later reveal that Asher is no longer sleeping next to her. Could it be that he had already floated up toward the ceiling that night—and many other nights before? Calling her his “angel” as she falls asleep, maybe the truth is that Asher amounts to her angel. By coming across as more devilish than she does (thanks to the privilege of white womanhood). This allows her to more fully believe and invest in her delusions about herself as the real do-gooder of the operation despite knowing, fundamentally, that she’s probably even more narcissistic than Asher. A narcissism that has evolved and grown stronger as a “chromosome” in los blancos over many centuries of enjoyed hegemony.

Thus, Safdie and Fielder challenge us to ask: is “the curse,” at its core, simply karma catching up to white people after centuries of employing various forms of subjugation and colonialism? After all, it’s not anything new to say that gentrification is the new colonialism. What is new, however, is the idea that the Earth might actually finally be having a visceral reaction to white people’s bullshit and therefore forcibly ejecting them from its atmosphere. Which, in all honesty, means Whitney might be next if there ever happens to be a season two.