John Cassavetes has always been a master at capturing the complexities of long-term monogamy. From his early work that preceded Faces, including Too Late Blues, to his later masterpieces, like A Woman Under the Influence, the auteur has always handled the subject matter of relationships with the grit and no frills approach of a psychological thriller.

As his fourth feature, Faces finds Cassavetes hitting his stride with regard to the slow and then abrupt burn of relationships. In many ways like several films in one, the narrative begins with a sort of meta screening of the film as Richard Forst (John Marley, later of Love Story and The Godfather acclaim) demands, “Roll it,” after hearing the men in suits describe their near nervous breakdown in crunching the numbers on this film.

From there, we’re introduced into the free-wheeling world of the Losers’ Club, an aptly titled nightclub where malaise-laden denizens of Los Angeles go for a good time. One of the frequenters of said watering hole is an elegant sort of prostitute–escort, really–named Jeannie Rapp (Gena Rowlands), who takes Richard and a ribald married man, Freddie Draper (Fred Draper), back to her house. There, a contentious exchange ensues after minutes of revelry shot in quintessential cinéma vérité-style are interrupted by Freddie’s mention of payment and an irascible attitude over Jeannie’s blatant preference for Richard.

As the two leave, she begs Richard to stay by kissing him. With a certain sadness he continues out the door, going back to his wife, Maria (Lynn Carlin). From the moment he arrives at his house, there is a strange tenseness filled with a mixture of levity and resentment that tinges the rapport Richard and Maria have. One minute saucy, Maria will say things like, “I feel very very bitchy tonight,” and the next she’ll show mild traces of affection by suggesting that she and Richard do something together like go to the movie (she proffers the notion of an Ingmar Bergman film, to which Richard replies, “I don’t feel like getting depressed tonight.”). All of it leads up to Maria’s insistence that she’s essentially become a hole to him, always wanting nothing more than sex from her–which is at least a somewhat positive marriage attribute compared to the sexless kinds of today.

As she runs up the stairs to try and avoid giving in to his carnal desires, Cassavetes cuts to the two of them post-coitus, with Richard telling a series of jokes they both laugh at, like, “What does Dracula do every night at midnight? He takes a coffin break.” This interchange reveals a stratum of intimacy that can only exist after years spent with the same person, cultivating a comfort level that takes a certain amount of domestic perseverance to create.

Even so, Richard asks for a divorce in the simplest, most brusque manner after the duo attempts to fall asleep, only for Maria to end up sauntering down to their bar to pour another drink. Richard follows her, stating, “I want a divorce.” When Maria starts laughing, assuming it’s another one of Richard’s jokes, he adds, “Did you hear what I said?” Realizing he’s serious, she stops, prompting Richard to cruelly conclude, “I want a divorce, that’s the only thing to do, isn’t it? Well, why don’t you laugh? It’s funny.”

With that, he goes to the telephone and calls up Jeannie right in front of Maria, offering to meet the former at the Losers’ Club again. And so, in one fell swoop years of familiarity and companionship are tossed out the window purely because Richard’s boredom and dissatisfaction has reached a crescendo.

Though Jeannie does agree to rendezvous with Richard, her detainment by a crude businessman, Jim McCarthy (Val Avery), and his colleague, Joe Jackson (Gene Darfler), leads Richard to come over to her house again, interrupting the strained saturnalia taking place. As Jim leaves Joe with the other prostitute to attempt wooing Jeannie by giving him a sob story about his “kooky” wife and tennis shoe wearing son, Jeannie soon discovers he only led her back to the bedroom to make it seem as though he had actually done something sexual with her to the others. Irritated by his presence, Richard surprisingly smoothes things over after engaging in a loose fist fight with Jim. Promising to call each other on Monday from the office, Jim and Joe leave with Jeannie’s female compatriot in tow.

Meanwhile, Maria tries to distract herself as well by going to the Losers’ Club with a gaggle of her friends, the uppity wife of Freddie Draper, Louise (Joanne Moore Jordan), also joining. It is there that the quartet of women encounter an attractive Joe Dallesandro-type, Chet (Seymour Cassel), dancing without a care, and sidling up to them because, as he later says, he could tell they felt excluded.

When Maria takes him and her friends back to her house, it becomes clear that one of her less “fresh” cohorts, Florence (Dorothy Gulliver), is especially titillated by Chet, remarking to Maria, “You know, these dances, these wild crazy dances–I think they’ve succeeded where science failed. ‘Cause you know, I can go to a beauty parlor and sit there for hours having my hair done and my nails polished, but I don’t feel any younger. I might look it, but these dances, these wild crazy dances–they do something to me inside.”

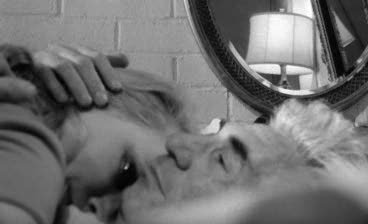

Soon after, she asks Chet to drive her home in Maria’s car. He returns later to consummate the sexual tension that had been building between them, with Maria shyly noting, “I feel better with the lights off.” The next morning, Chet discovers that she’s overdosed on sleeping pills, rushing to the phone to call for help, only to backpedal when he remembers he doesn’t even know Maria’s number, nor does he want to deal with the police. Thus, he forces her to throw up in a scene that doubles as one of erotic violence. When she finally comes to, Chet freely admits that he loves her, followed by mentioning that he also hates her. This frequently explored theme in Cassavetes’ work–one that espouses the thin line between love and hate–is punctuated by Chet’s lamentation, “No one wants to take the time to be vulnerable to each other.” Primarily because when you do allow yourself to be vulnerable, you’re subject to inevitable loss and heartache. Thus, another sentiment Chet bewails, “It’s ludicrous how mechanical people can be,” is a direct result of so many not wanting to get wounded. Because recovery can be close to impossible, particularly for women.

Even Jeannie, who admits to Richard, “You’re a son of a bitch because you get to me,” finds herself aggrieved by Richard’s insistence, “Don’t be silly anymore. Just be yourself.” This accusation of her being fake leads to one of the most iconic scenes in the film: Jeannie silently shedding a tear from the door frame of the kitchen as she clears away the plate of eggs Richard criticized for being overcooked. Hence, even the novelty of Jeannie wears off for Richard by the morning, as he returns home to catch a glimpse of Chet fleeing the scene, and Maria shouting at him, “I hate my life and I don’t love you anymore!” But still, it was Richard who set the wheels in motion for a separation, heightening Jim McCarthy’s harsh assessment of the expendability of women by laughingly asking Richard and Joe, “Did you know that almost all women are whores?”

For some of us, admitting to desolation and ennui is the first step toward a relationship’s demise. Because rather than fix what’s wrong with ourselves, we look to the other person as the source of blame for why we’re unhappy.