When The Great Dictator came out in 1940, Charlie Chaplin had no idea of the extent of the atrocities being carried out in Nazi concentration camps. Later, in his 1964 autobiography (My Autobiography), Chaplin would state that had he known just how severe the carnage was, he wouldn’t have made the film. Let cinema-going audiences then thank the silver screen gods that Chaplin wasn’t fully aware, otherwise we wouldn’t have this timeless masterpiece to crop up over and over again to remind us just how big for one’s britches a single man with a height and talent complex can get. Where Germany is defeated in The Great War of 1918, for film revisionist (read: non-lawsuit) purposes, Tomainia is defeated. One of the fighting soldiers for said fictionalized country, a rather daffy, clueless Jewish barber, ends up–through pure luck and circumstance–coming to the aid of a Tomainian pilot named Schultz (Reginald Gardiner). After a series of zany hijinks, the two crash land while high-tailing it away from the enemy, giving the Jewish barber (any resemblance to the great dictator is “purely coincidental”) amnesia.

During the time in which he remains in the infirmary, an entire twenty years passes, allowing for the rise to power of Adenoid Hynkel (also played by Chaplin). When the barber finally decides, on the randomness of whim, to simply return to his ghetto one day as though nothing has ever happened, he returns to the sight of Hynkel’s Storm Troopers scrawling “JEW” in paint on the window of his shop. A kindly and rebellious-spirited woman, Hannah (Paulette Goddard), who lives next door defends him by bludgeoning some of the Storm Troopers on the head with a pan. It is thus that a friendliness complicit with inexplicable attraction is forged. But Hannah and the barber’s brand of dissent isn’t liable to stand for very much longer as Hynkel’s increasing irascibility makes him more prone to erratic behavior. It is only because Hynkel’s commander of the troops, Schultz, recognizes the Barber as the man who saved his life in the war that he and Hannah are spared.

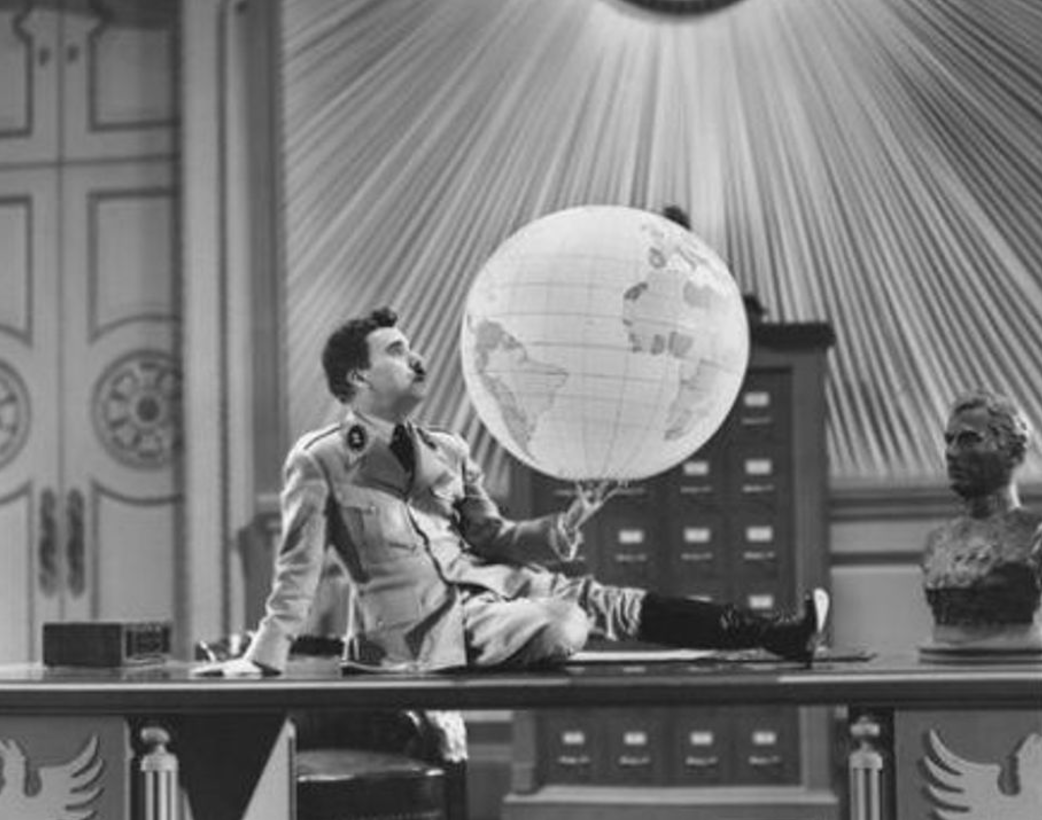

Delivering two diametrically opposed yet eerily similar in jejuneness performances, Chaplin’s delivery of Hitler’s always gibberish-sounding rhetoric (no doubt gibberish-sounding even when translated) was a result of studying Leni Riefenstahl’s unfortunate masterpiece, Triumph of the Will, which he first saw at a screening that took place at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Incidentally, like one certain current president comparable to Hitler, the dictator that inspired the film expressed in his manifesto, Mein Kampf, that the general ignorance of the masses makes appealing to their emotions by far more important than appealing to their reason–hence Triumph of the Will‘s dramatically overblown nature. The Great Dictator follows a similar path in its parody. From Hynkel’s petulant demands (“Listen, you blockhead. Mobilize every division of the army and the air force. Proceed to Bacteria and attack at once!”) to the send-up of Joseph Goebbels in the form of Garbitsch (Henry Daniell)–yes, pronounced Garbage–no aspect is left without an over the top portrayal. It is in Garbitsch’s stead as Hynkel’s righthand man/Minister of Propaganda that he feels inclined to espouse to the supporters of the party, “Today, democracy, liberty and equality are words to fool the people. No nation can progress with such ideas. They stand in the way of action. Therefore, we frankly abolish them. In the future, each man will serve the interest of the State with absolute obedience.” Chaplin’s brilliant screenplay is almost more tragic than it is comical, as this is exactly how people in power of this mindset truly feel. The iconic scene of Hynkel dancing serenely with a balloon in the shape of Earth only to burst into tears when the balloon itself finally bursts, speaks to just how out of touch the man with a dictator’s psyche is when it comes to toying arbitrarily with the lives of, oh, millions.

When the caricature of Mussolini, Napaloni (Jack Oakie), is summoned to Tomainia from Bacteria (the more than somewhat unflattering alter ego of Italy), the ridiculous psychology of the common tyrant is even further lambasted, culminating in a food fight with many phallic Italian-inspired foods. Because truly, aren’t all such rulers trying to prove that they can put the “dic” in dictator by trying to swing theirs as widely over their “territory” and beyond as possible? For it can’t seem to be disproved that no matter how far into the future we get, this very primitive motivation for why men do what they do will never change. Yet there are still reprieves of peace and relative calm in between these valleys of autocratic egoism.

As one of the title cards in the film describes: “This is a story of a period between two World Wars–an interim in which Insanity cut loose. Liberty took a nose dive, and Humanity was kicked around somewhat.” So it goes in the present moment, which we must look to as just another interim in which insanity has cut loose.