After a project as sentimental (in large part due to being written by Jack Fincher) as David Fincher’s last one, Mank, one might believe that, on the surface, The Killer is an “edgier,” more “hard-boiled” movie. But the truth is, the eponymous killer in question (Michael Fassbender) is just a big teddy bear. Hence, his repeated playing of The Smiths while on the job or otherwise. Of course, listening to The Smiths might not necessarily be a dead giveaway (no pun intended) of a person’s empathy. In fact, based on Morrissey’s more recent “brand” (characterized by a generally white supremacist, “Britain First,” anti-immigrant stance), one could argue that listening to The Smiths is very much the mark of someone willing to kill. And yet, for those who can still only focus on the lyrics sung by Morrissey, rather than the words said by him in a public forum, it’s hard to forget that he was once a spokesperson for the downtrodden and marginalized. Those who were relegated to the fringes of society for their “strangeness.” But naturally, that sort of messaging was bound to evolve into becoming a “security blanket” for serial killers and incels.

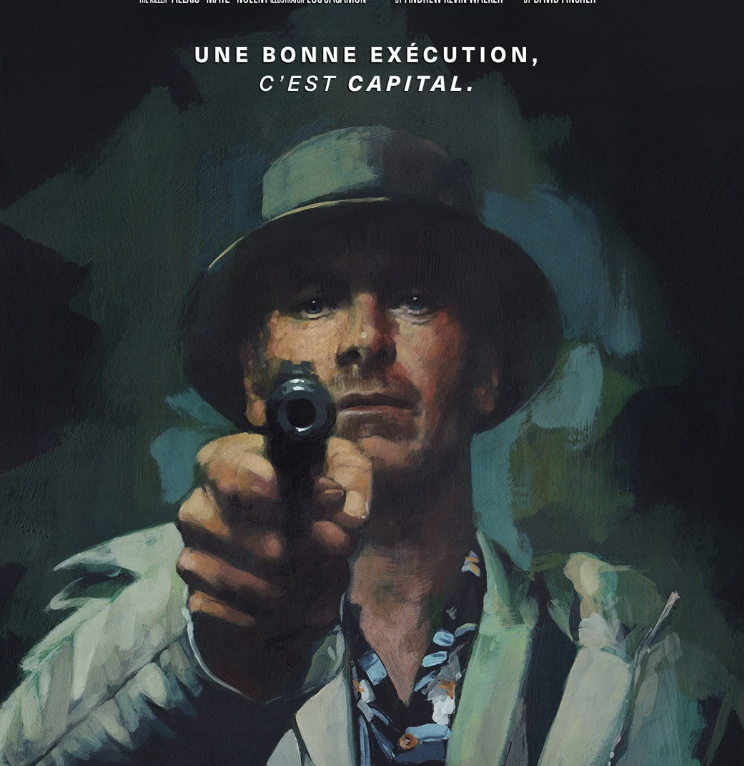

The Killer, surprisingly, doesn’t fall into the latter category, as we quickly find out after he botches a hit in Paris. But not before he gives the rundown on what it truly “is” to be hitman. Delivering his internal monologues like a clinical “how-to,” the first “chapter” of the movie finds The Killer at his most Patrick Bateman/Tyler Durden-y. Not least of which is because of his calm, stoic tone as he says things like, “If you are unable to endure boredom, this work is not for you.” Indeed, The Killer seems determined to debunk the myth of “hitmanning” as something “glamorous” more for himself than anyone else. And yet, it’s obvious that he can’t deny the glamor it has afforded him. The “culturedness” he feels he possesses as a result of being ping-ponged back and forth between far-flung travel destinations. To places like Paris, where most people will only ever dream of visiting. As a matter of fact, The Killer is sure to wax poetic about said town when he remarks, “Paris awakens unlike any other city. Slowly. Without the diesel grind of Berlin or Damascus. Or the incessant hum of Tokyo.” Such overt love for the unique ways in which Paris sets itself apart (that word is also key to understanding how The Killer sees himself) likely stems from the screenplay, written by Andrew Kevin Walker, being based on French writer Alexis “Matz” Nolent’s graphic novel (illustrated by Luc Jacamon) of the same name. In truth, part of what lends the film such a, let’s say, “Guy Ritchie flair” (no offense to Fincher) is its basis on such source material (side note: Ritchie has a graphic novel series called The Gamekeeper).

Despite Paris’ uniqueness, it certainly does attract quite an army of basic bitches (ahem, Emily Cooper—and, quelle surprise, the same block where Emily’s apartment is located in Emily in Paris is also used as the filming location for where The Killer’s mark lives). Which actually makes it the perfect place to hide amongst the “normals.” Not that The Killer sees himself as anything particularly special. As he puts it, “I’m not exceptional. I’m just…apart.” The Killer additionally informs us that there is no such thing as luck, destiny or “justice.” Life is a random smattering of occurrences before which we all eventually die. Such nihilism is befitting of an avid The Smiths listener, but, in reality, more so a Depeche Mode listener. And The Killer might actually have turned out to be more adept at his job had he opted for the latter band as part of his “Work Playlist.” Alas, he favors the electric guitar melancholy of The Smiths to the electronic melancholy of Depeche Mode.

To be sure, listening to Depeche Mode as one’s “killing soundtrack” would be more in line with (unknowingly) quoting occultist Aleister Crowley by saying, “In the meantime, ‘Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law.’” All of this callous, calculated posturing, we quickly find out, is nothing more than the internal “Jesus Prayer” he repeats to himself on a loop in order to keep doing the job…to keep assuring himself that he wants to do it. And yes, there’s even an official mantra for that “Jesus Prayer”—one he repeats before every kill: “Stick to your plan. Anticipate, don’t improvise. Trust no one. Never yield an advantage. Fight only the battle you’re paid to fight. Forbid empathy. Empathy is weakness. Weakness is vulnerability. Each and every step of the way, ask yourself: what’s in it for me? This is what it takes. What you must commit yourself to. If you want to succeed.” And then, of course, he biffs the shot—missing his intended old rich white man mark so that it instead hits the dominatrix “entertaining” him. This gross error, needless to say, goes against everything The Killer has tried to get both himself and the viewer to believe about who he is up until now. Not to mention the fact that those lines about forbidding empathy because it’s a weakness are in direct contrast to 1) listening to The Smiths ad nauseam and 2) the majority of lyrics written by The Smiths.

Yet perhaps what keeps The Killer on the hook with this highly dangerous profession is the obvious masochistic adrenaline rush he gets from it. To that end, it’s apparent that for as blasé and “put upon” as he is by his work, he still “loves” it. Or at least, the aspects of it that require more “creativity” on his part. “Staged accidents, gradual poisonings,” that sort of thing. But more than having “enthusiasm” (of a Daria Morgendorffer nature) for the art of being a hitman, he seems to relish most of all the idea that doing this work is what sets him apart from what he calls “the many.” The plebes, the hoi polloi. Those foolish (or, perhaps more accurately, “nice”) enough to let themselves be exploited. So it is that he warns, “From the beginning, the few have always exploited the many. This is the cornerstone of civilization. The blood in the mortar that binds all bricks. Whatever it takes, make sure you’re one of the few, not one of the many.” In choosing to be a hitman, that’s essentially what The Killer is trying to make sure of for himself. Paired with a steadily applied aura of “I don’t care” and “Nothing means anything,” this is The Killer’s bid to spare himself from any pain…or guilt. At one point, just before taking the botched shot, he even insists, “If I’m effective, it’s because of one simple fact: I. Don’t. Give. A. Fuck.”

But oh, how he gives a fuck. A big fuck. That’s what the audience is about to witness as the true genre of the The Killer becomes unveiled after “Chapter One”: revenge. A movie trope as tried-and-true as PB&J, The Killer quickly becomes reminiscent of Kill Bill: Vol. 1 as our hitman sets out to seek and destroy the parties responsible for brutalizing his beloved live-in girlfriend, Magdala (Sophie Charlotte). Indeed, the sudden revelation of her existence is, again, counterintuitive to everything he’s tried to tell us about himself. The discovery of her vicious assault (told by a trail of blood throughout their house as Portishead’s “Glory Box” plays loudly) is an unwanted “plot twist” he learns of almost immediately upon returning to Santo Domingo. But then, it was already The Killer who warned us, “Of those who like to put their faith in mankind’s inherent goodness, I have to ask: based on what, exactly?” And based on the state of Magdala, it can be said that there is only inherent evil in this world. Even if some would argue “karma,” “you reap what you sow,” etc. of what happened to The Killer’s girlfriend. Still, it’s not as though Magdala ever hurt anyone (as far as we know). Why should she be the one to suffer the consequences of The Killer’s error?

Luckily, one supposes, she has a man willing to go on an odyssey to avenge her bodily violation (by the same token, she’s unlucky enough to be in love with a hitman that would create the sort of circumstances in which such a horrible thing could happen to her). An odyssey that takes him through New Orleans, St. Petersburg (Florida, not Russia), Beacon (where Tilda Swinton is given her moment to shine as The Expert) and, finally, Chicago. Right back to the very source of how this whole vicious circle began: the client. A billionaire named Claybourne (Arliss Howard) who swears to The Killer that he has no problem with him. That any “trail scrubbing” that was done had been a result of Hodges’ (Charles Parnell)—The Killer’s “handler”—advisement. Being “green” to the game of taking out a hit, Claybourne readily agreed to such a recommendation…never anticipating that the “blowback” he hoped to avoid would instead come in the form of the hitman himself.

Seemingly “satisfied” with the billionaire’s answer, The Killer leaves him unscathed in his deluxe apartment in the sky (funnily enough, the name George Jefferson happens to be one of The Killer’s many aliases). Which might be the most telling of all regarding his weakness, his propensity for being just like one of the “many” so willing to be exploited by the few.

From the drab, gray cinematography of the Chicago section, Fincher cuts back to the bright vibrancy of Santo Domingo, where a healed Magdala awaits The Killer poolside in their backyard. Perhaps sensing our preparedness to call him a sellout after all that railing against empathy and vulnerability, The Killer reasons, “Maybe you’re just like me. One of the many” (still a narcissistic way to phrase it; you know, instead of saying, “Maybe I’m just like you”). At this, his eye twitches, as though it pains him to admit it. But admit it he does. And then comes the rolling of the credits to the tune of “There Is A Light That Never Goes Out.” Ironic, considering The Killer’s full-time job was to, let’s say, “dim lights.”

But the song lyric from The Smiths that remains most apropos (and which serves as the very first one The Killer plays in the film) is from “Well I Wonder”: “Gasping, dying/But somehow still alive/This is the final stand of all I am.” When applied to The Killer, it’s evident that the final stand of all he is remains merely, ugh, human…and he needs to be loved; hence, weak and vulnerable. So, again, if you want to be a truly cold-blooded hitman: Depeche Mode for the win.