For anyone who has ever vehemently believed in their god-given right to fame–regardless of the caliber of talent exhibited–Martin Scorsese’s 1983 film, The King of Comedy is the answer to your prayers. Once again, Scorsese enlists Robert De Niro for the role of anti-hero in the form of Rupert Pupkin (“it’s often misspelled and mispronounced,” he admits). Like a less volatile Travis Bickle, Rupert, too, seeks to carve out his place in the world–whether the powers that be accept him or not.

In this instance that “power” is Jerry Langford (Jerry Lewis) of the popular nighttime comedy program, The Jerry Langford Show. Considering the placement of this film in Scorsese’s oeuvre, it’s easy to note a gravitational pull the auteur felt at this time to the macabre, as The King of Comedy succeeded the gritty Raging Bull and preceded the highly underrated, even darker comedy, After Hours. Scorsese’s focus on a displaced protagonist more than mildly out of touch with reality speaks to a time when the middle class was just starting to become pushed to the side (Reagan-dominated were the 1980s, after all). And when the middle class can’t dare to dream, weird shit definitely starts to happen.

Though in fellow obsessed fan Masha’s (Sandra Bernhard, in one of her first major movie roles) case, coming from extreme wealth doesn’t exactly bode well for sanity either. As the film commences with Jerry leaving his studio and a slew of stage door fans bum rushing his car, we find that Masha has weaseled her way into the vehicle. Somehow, Rupert manages to switch places with her and talk Jerry into driving him to the next available corner. Though uneasy and faintly irritated, Jerry appears accustomed to these types of run-ins (more of which we’ll see throughout the film, with one old woman even wishing cancer upon him for not talking to her son on the pay phone he happens to pass by). To get Rupert out of his hair, Jerry tells him to call his office to audition for the show.

Rupert, already highly susceptible to extreme fantasy as it is–many of which feel interchangeable with the reality we see him in–soon after goes to Jerry’s office to insist that he’s been hired to be a stand-up comedian on the show. Jerry’s receptionist and assistant play along nicely with him at first, the latter agreeing to listen to one of his tapes if he brings it in.

Meanwhile, the girl he’s pursued for some time now at the local bar, Rita (Diahnne Abbott), gets roped into his antics when Rupert insists he’s friends with Jerry, and that he’s been invited to spend the weekend at his country home. Buttering her up in his mind with the pitch, “Rita, every king needs a queen. I want you to be mine,” Rita can’t help but go along with it until she unearths just how severe Rupert’s delusions of grandeur are.

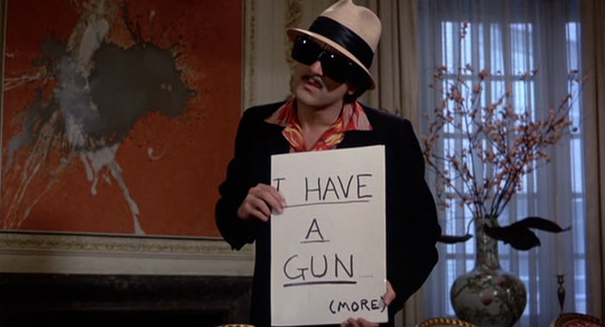

With Rita lost to the real world again, Rupert decides to go back in league with Masha to kidnap Jerry and force him to agree to let him open the show that night. Masha, one of the few willing participants in Rupert’s alternate reality, has her own self-directed reasons for getting involved–most pressing among them her desire to have sex with Jerry (making for one of the most hilarious and surreal scenes of the film). Again, of course, this emphasizes the ways in which everyone in Scorsese’s stylized universe is reacting–or rather waiting–to serve their own interests.

A prescient look into the future (New York has always been ahead of the curve in selfishness), all of the principal characters in The King of Comedy are simply tapping their feet in anticipation for the others to stop vying for attention so that they themselves can bid for it. Rupert’s constant search for approval–validation of any kind–can’t be quelled, nor can it ever be received in seemingly any way from those he wants it from: that nebulous entity known as the masses. While standing in front of his cardboard cutout audience (among other cutouts in his room are of Jerry Langford himself and Liza Minnelli), Rupert represents so many people of the current generation, desperate to be famous in some field they really have no talent in. But as The King of Comedy iterates, talent is always secondary to sensationalism. It’s like Rupert says, “Better to be king for a night than schmuck for a lifetime.” It’s sort of a re-working of Indian sultan Tipu Sahib’s aphorism: “Better to live one day as a tiger than one hundred years as a sheep.” Except in this case it’s geared toward how one can best secure notoriety. That proverbial place in the sun that might ultimately scald them, but God, how good it feels in the moment.