When a show like The Sopranos, as perfect in its time and place as it was, is revived, the best option for doing so—if absolutely necessary (which it never is)—is to somehow still make it exist in the past so that it can sustain some of the “magic” that no longer remains for it in the present (something …And Just Like That might have wanted to take into account). One supposes this was part of the logic behind The Many Saints of Newark for The Sopranos creator David Chase and his co-writer, Lawrence Konner. Hence, the “eureka!” “solution” of making a prequel that would be set in a decade when it was even easier to get away with racism and misogyny, especially as a mafioso Italian-American. Yet even in this regard, Chase and Konner seem afraid to push the limits or test the boundaries in any real way, instead wanting to stick to their safe little story about “Why Tony Soprano Became Tony Soprano”—something we already knew when the series ended back in 2007. Indeed, the tagline of the movie is, “Who Made Tony Soprano.”

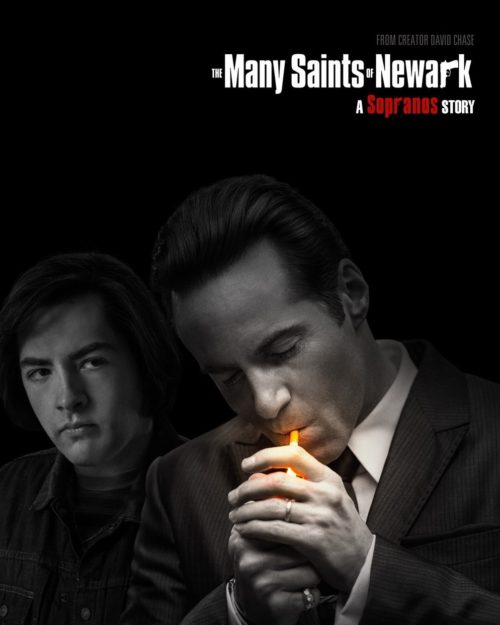

Apparently, this question—one that could have been answered in two words [Dickie Moltisanti] within a novelization of the story (à la Once Upon a Time in Hollywood)—seemed enough to warrant creating an entire film. And maybe the desire to make one stemmed from the fact that The Sopranos was originally conceived as a feature about “a mobster in therapy having problems with his mother.” Incidentally, that doesn’t sound entirely unlike the premise for Analyze This… In any case, it feels like Chase wanted to make some version of the movie he never originally did about Tony (James Gandolfini), even if it’s less about him and more about his honorary uncle, Dickie Moltisanti (Alessandro Nivola, carrying a large bulk of the narrative on his shoulders). But Dickie, of course, is meant to serve as that titan of an influence on Tony that made him into what he became in 90s and 00s New Jersey, ergo The Many Saints of Newark maintains it’s still, at its core, “about” Tony. And, as usual, his “psychology.” Yet since the movie favors a highlight of the Moltisanti bloodline (built into the title, as “moltisanti” means “many saints”), we don’t even get the benefit of the story being told from Tony’s perspective, but rather, a “from beyond the grave” Christopher (Michael Imperioli). Probably the only attempt at a creative gimmick about this film.

As viewers of The Sopranos know, Christopher was Tony’s beloved protégé, often referred to as his “nephew” (despite being Carmela’s [Edie Falco] cousin once removed)—the same way Dickie looks upon young Tony in The Many Saints of Newark. Especially since Tony’s own father, Johnny (Jon Berthal), is in the clink for four extremely formative years of Tony’s youth. What’s more, considering Dickie’s death (read: murder), and the relationship he has with Tony, the latter’s affection toward Christopher makes plenty of sense. What doesn’t is the need for The Many Saints of Newark to drive this point home when we’re already well-aware of these “epiphanies” and backstories. Unfortunately, the one major plot twist involving Corrado “Head Giver” Soprano (Corey Stoll) and Dickie feels pulled out of thin air for the sake of drumming up more interest in the film as something to be studied against the series.

As we watch and wait for some arcane purpose for the film’s existence to reveal itself, we see history repeat itself in a meta sort of fashion by “pre-repeating” itself (“prepeating,” if you prefer). For Dickie embodies all the same problems and moral quandaries that Tony will face later on, including the decision to murder his ultimately “pesky” goomah, Giuseppina (Michela De Rossi). Well, in this case, Tony only threatens (quite seriously) to kill Gloria Trillo (Annabella Sciorra), which is perhaps what ultimately drives her to suicide—but still. There are overt parallels between Dickie and Tony’s behavior, more so than there are between Dickie and his own son. Even the presence of Salvatore “Sally” Moltisanti as a sub-in for the therapist figure that Dr. Melfi (Lorraine Bracco) will become offers a correlation between Dickie and Tony, with both in need of having a “confessor” to legitimize their respective belief that they’re doing their “best” to “be good.” In spite of only performing “good deeds” to counterbalance all the bad they know they’ve done.

A central aspect of the plot in The Many Saints of Newark isn’t just Dickie juggling his responsibilities to the DiMeo crime family with being a mentor to Tony and a semi-regular “boyfriend” to Giuseppina (who looks an awful lot like a feminized Christopher), but also the riots that take place in the city in July of 1967. Like so many incidents that set off outraged protests among the Black community, this, too, was caused by an instance of police brutality against a single man. Specifically, a cab driver.

In The Many Saints of Newark, Chase’s slight revisionism shows the cabbie obeying the demands of a mafioso telling him to make an illegal right turn in order to drop him off. Against his better judgment, the driver adheres to the request, immediately pulled over afterward and beaten to a pulp. With the lingering plot of these riots and racial “flare-ups” in the background used only in terms of how it affects the (mafia-affiliated) Italian-American population of Newark, Chase and Konner miss their chance to address the long-standing tensions, as well as frequent similarities in marginalization, between Italian immigrants and Black people. Instead, it seems as though they would rather stay just on the periphery of exposing that tension to its fullest, wielding the character of Harold McBrayer (Leslie Odom Jr.) to say the racial slurs (namely the classics, “guinea” and “wop”) required to evince the hostility between races.

Markedly, however, there is more restraint on the side of the white Italians, never dropping even so much as the “n-word.” It’s almost as though, not wanting to make the same mistake Entourage: The Movie did in refusing to acknowledge that any time had passed since the “good ol’ boys” culture of the show was allowed to thrive so unchecked by audiences, Chase and Konner sought to play it as politically correct as they could. Which is fairly incongruous when taking into account the subject matter. Here, too, there was an ideal opportunity to underscore the rarely-addressed-in-pop-culture matter of Italian racism toward others (and even toward themselves, based on regional divides).

With The Many Saints of Newark, not only do Chase and Konner hedge their bets by setting the narrative within a time frame that “permits” the characters in their universe to get away with bad behavior more easily, but they also rein in said characters’ dialogue and action far more than they would have at the height of The Sopranos’ original airing period, a time when fear of cancel culture was barely on anyone’s radar.

Another key complaint from anyone with even the remotest knack for identifying underused dynamic potential is the fact that Tony’s mother, Livia (played here by Vera Farmiga, coming across aesthetically as a real Carmela Soprano type), is barely brandished for full effect. There are some small moments when her influence over and impact on Tony is revealed in the scenarios when he gets in trouble. Like when a guidance counselor scolds him after he steals the answers to a math test to cheat from and then calls his mother in to inform her that Tony is actually a very bright boy with obvious leadership capabilities. What’s more, that Tony described to her one of his best memories of his life: Livia reading to him from a children’s book about Sutter’s Fort and then cuddling up to him to hug him when he was younger. This, naturally, was on a night she must have been particularly vulnerable, for Johnny was “away.” Whether on “business” or with his goomah, neither explanation would be of much comfort to Livia, even then looking to Tony for something like “Oedipal comfort.”

To the dismay of those hoping for The Many Saints of Newark to at least function as the “standalone movie” it wants to be, it regrettably comes across as mediocre at best—another subpar mafia movie that Ray Liotta felt obliged to make in a never-ending bid to match what he did in Goodfellas. As Chase, in turn, attempts to match what he did with The Sopranos. And so, for those looking for something like a “prequel” that’s actually worthy, it’s probably going to be more satisfying to keep turning to Trees Lounge.