In every adolescence, there is a period characterized by feelings of isolation and loneliness. For the protagonist of Microbe & Gasoline, fourteen-year-old Daniel Guéret (Ange Dargent) a.k.a. Microbe–a nickname bequeathed to him thanks to his small stature–these sentiments feel more eternal than temporary. Although he blends in easily enough with Laura (Diane Besnier), a girl who has relegated him to the friend zone in spite of his intense crush on her, he has little in the way of camaraderie to dilute some of his more solitary hours–often characterized by drawing pictures of nude women and masturbating to them without ever reaching that final release.

On the heels of The We and the I (2012), Michel Gondry continues to showcase an empathetic sensibility toward those struggling to discover their identity and truly be comfortable with it. For Daniel, the constant thought of inevitably dying plagues him, and it is a fear he mistakenly confesses to his highly over-intellectualized mother, Marie-Thérèse (Audrey Tautou, who might be more of a muse to Gondry than she is to Jean-Pierre Jeunet of late). Indeed, a large portion of the tension Daniel feels in life is because of Marie-Thérèse, of which he notes, “My mother loves me too much. I feel sorry for her.” But beyond her, it is a feeling of having no sense of place among his peers–that is, until Théo Leloir (Théophile Baquet) appears onto the scene like some sort of Jesse Eisenberg-inspired mirage.

Of course, because of his precocious nature and a certain odor of motor oil emanating from his pores, Théo is dubbed with a moniker that is as similarly unpleasant as Microbe’s: Gasoline. But Microbe pays no mind to what the other students say about him, even Laura, who he chastises for judging others too quickly based solely on outward appearance. The two soon develop a fast friendship based not only on common ground, but on the symbiotic notion of two loners needing to feel just a little less ostracized. As the school year progresses and Daniel embraces his status as pariah after holding an art show centered around punk paintings of his brother, his brother’s friends and Théo that no one comes to, the friendship becomes about something more than merely not feeling alone. Rather, it becomes a matter of growing, both as a person and into oneself.

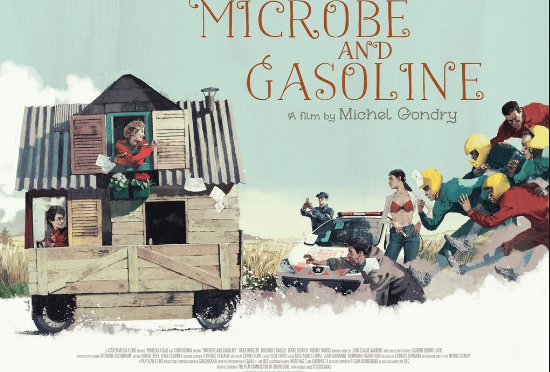

It is at this point that the duo concocts a plan to build a car disguised as a shed to travel through the French countryside from Versailles over the summer. It will be something they’ve carved out just for themselves, a form of independence and freedom never before known. And though they give up at first on the notion when the plan encounters a hitch, Gasoline’s recounting of Charles De Gaulle’s example of persistence during wartime re-incites their will to go forth.

With each one lying to their parents about their whereabouts for the summer, the trip begins in relative harmony as their plan to conceal the nature of the vehicle from police by disguising the car as a shed works seamlessly. It isn’t until they park the car in the backyard of a creepy dentist and his wife that the journey begins to get a bit weird, with said dentist making the common mistake that everyone else who encounters Daniel does: that he’s a girl (it’s like a reverse version of Abbi Jacobson on Broad City Syndrome).

It is at this point in the film that a shift is signaled, one that favors hijinks in addition to philosophical meanderings. For the duration of Microbe & Gasoline, Gondry exhibits a surprising amount of restraint with regard to his predilection for surrealism, but as the third act approaches, the auteur proves himself unable to resist giving in to his usual modus operandi, with scenes of Microbe’s imagination running away with itself manifesting in the form of Laura appearing to him in a red bathing suit on the beach and hallucinations of everyone on a plane he’s riding in falling asleep en masse.

While, at first, Gasoline is the guru Microbe turns to for advice in all matters, absorbing wisdom from the former such as, “It’s rather crass to point out your generosity to people,” it becomes evident that he is gradually coming into his own, making his own decisions about how to feel and be. For instance, when Gasoline does everything he can to convince Microbe to forget about Laura, Microbe insists, “I don’t want to not be in love. It’s a noble, beautiful kind of pain,” to which Gasoline balks, “No pain is beautiful.”

Gasoline goes on to instruct that the moment Microbe stops viewing Laura as someone special, she will be interested in him. But Microbe can’t fathom the point of wanting to be with someone if he doesn’t see her as special. Wanting to be as aloof and cavalier as Gasoline, Microbe decides the best course of action is to get his hair cut so as to stop being mistaken for a girl, but ends up doing so in a whorehouse which only leads to what Gasoline will later call a “samurai” coif. When the two are separated over a fight regarding Microbe’s selfishness, as well as the destruction of the car, Microbe is forced to fend for himself, putting into perspective just how much he values Gasoline.

And, just when Microbe thinks he might be damned to an existence without him, Gasoline returns to rescue him from certain parties involved in the whorehouse haircut incident. But alas, no friendship can exist outside the confines of societal pressures and opinions forever, and Microbe and Gasoline are forced by the elements to return to Versailles, where Microbe is faced with a new harsh reality that calls into action everything Gasoline ever taught him.

While symbiosis in friendship often favors the benefit of one entity over another, Microbe and Gasoline each glean something from one another that no one else could have given him. Though, admittedly, Gasoline is the true feeder of sagacity, as, in the end, Laura does get her affections reversed when Microbe stops caring. Just as Gasoline foretold.