It’s something, to be sure, that everyone has thought about, in one form or another. The idea of being able to get “another person” to go to work for you (apart from the option where robots take over all jobs and render humans obsolete). But why not let that person be another version of yourself, full-stop? Or rather, a part of your brain that only gets “activated” in the eight hours when you’re forced to be under the thumb of The Man (not that you’re able to avoid being under his thumb in some fashion for twenty-four hours a day). So it is that the notion behind the crux of Severance’s narrative certainly one-ups the idea Pee-Wee Herman offered back in the day during a Christmas special of Pee-Wee’s Playhouse when he put a blow-up doll of himself in front of the camera so he wouldn’t have to listen to the entirety of “The Twelve Days of Christmas” as sung by Dinah Shore over video phone (it was very ahead of its time, Zoom being such a long way off and all).

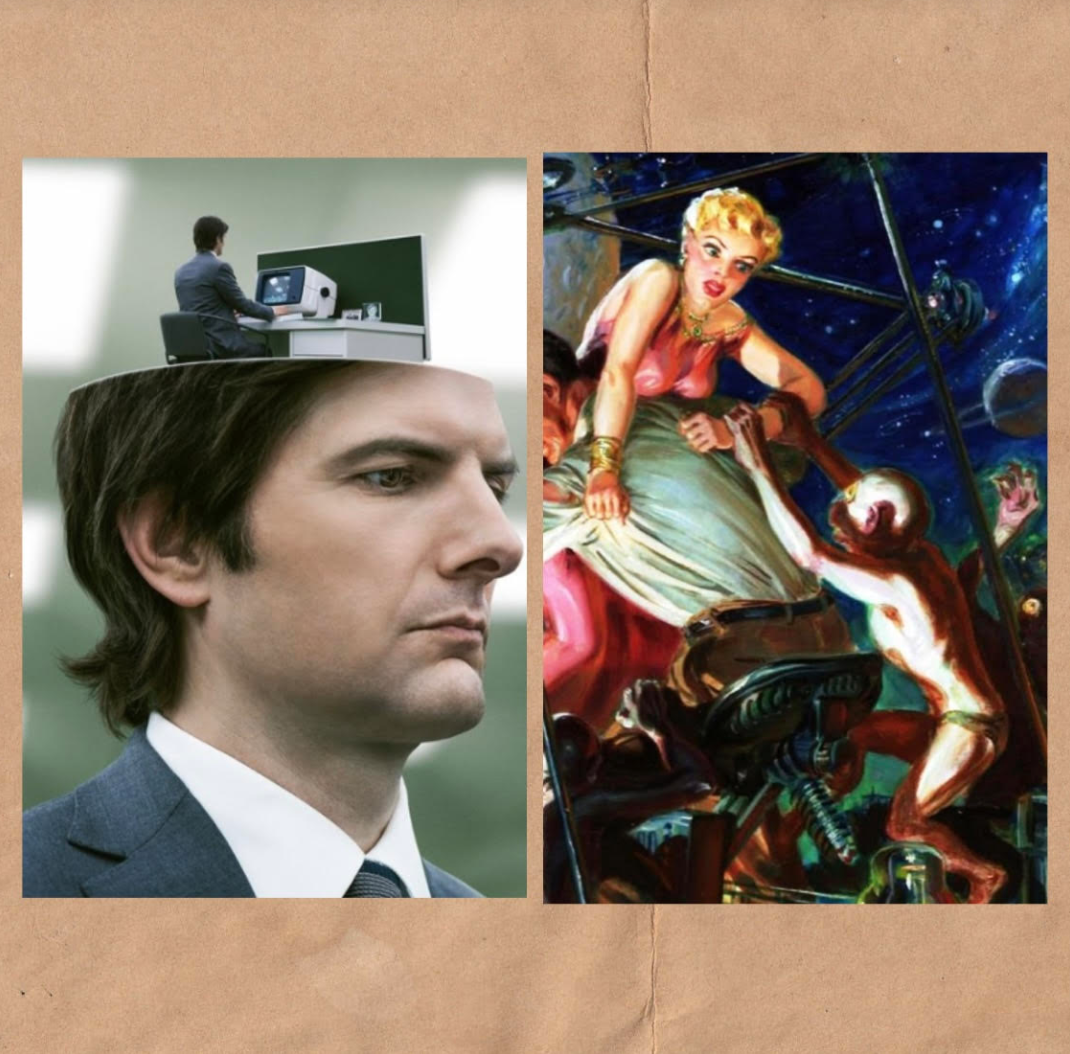

Created by Dan Erickson (who was charmed enough to get Ben Stiller on board to produce despite being a relative unknown in “the biz”), Severance follows the lives of four “severed” employees that work for a dubious biotech company called Lumon Industries: Mark Scout (Adam Scott), Dylan George (Zach Cherry), Helly Riggs (Britt Lower) and Irving Bailiff (John Turturro). All of them, however, are known to one another only as Mark S., Dylan G., Helly R. and Irving B. It’s very grade-school in a way, but also designed to maintain anonymity so that none of them get any ideas about investigating who they “really” are in the outside world. For they are the ones meant to live underground, toiling away in the darkness (or, worse still, the fluorescent lighting trying to mitigate the darkness).

Erickson’s premise, in many regards, thusly echoes a key aspect of H. G. Wellls’ The Time Machine, during which The Time Traveler encounters two new races of people in the far-flung future: the Eloi and the Morlocks. It’s clear that the severed employees embody the Morlocks, forced to live down at heel in the underground. Initially, The Time Traveler believes this to be a cut-and-dried case of aristocracy versus slave labor (Wells’ predilection for racist overtones usually coming into play in all of his stories). But later, he draws a different conclusion: “The Upper-world people might once have been the favored aristocracy, and the Morlocks their mechanical servants: but that had long since passed away. The two species that had resulted from the evolution of man were sliding down towards, or had already arrived at, an altogether new relationship.” One stemming from an inevitable rebellion on the part of the Morlocks—the “severed employees” in the comparison, if you will.

So it is that The Time Traveler further explains, “The Eloi, like the Carolingian kings, had decayed to a mere beautiful futility.” Perhaps that’s what can be said of rich people in general as well. But in Severance’s case, this description might eventually apply to the people who use their “slave self” for every unpleasant thing they don’t want to do, like, say, childbirth. An element that does come up thanks to Devon (Jen Tullock), Mark’s sister. About to give birth in some bougie lodge setup that her husband, Ricken (Michael Chernus), advocated for, she comes across another woman staying in a more expensive lodge while on the hunt for a cup of coffee. Despite the fact that the two have what Devon would call a fairly memorable conversation, the woman has no idea who she is the next time they happen to encounter one another.

Devon digs a bit deeper into the matter to find that the woman is Gabby Arteta (Nora Dale), the wife of a senator who backs legalizing severance for, well, just about every little task one could think of (yes, it sort of smacks of TaskRabbit, but more dystopian). Which is honestly such a rich person’s way to deal with things, in addition to monetizing the idea (echoing the adage, “The corporation will sell the noose to hang itself”) so that it can be sold in some way to the “little people.” Or rather, the middle-class ilk who might also be able to afford getting the procedure done.

In The Time Machine, too, the Eloi represent an allegory for the ultimately feeble and fainéant wealthy class, unable and unwilling to do much of anything for themselves. They are what amount to the “outies” in Severance: living their lives in relative peace without worry of the emotional and physical toll that working takes. But, in the long-term, if they were ever to somehow “lose” the severed self that actually works, it would result in the description The Time Traveler gives about the Eloi. How they “still possessed the Earth on sufferance: since the Morlocks, subterranean for innumerable generations, had come at last to find the daylit surface intolerable… But, clearly, the old order was already in part reversed. The Nemesis of the delicate ones was creeping on apace.”

In Severance, that “Nemesis” of the “delicate ones” is initially just Petey (Yul Vazquez), the former division manager of “Macrodata Refinement” (whatever the fuck that means). But as Petey makes himself known to Mark’s “outie,” he, too, starts to question everything about what’s really going on “down there.” The more overt Nemesis to the Lumon agenda is Helly R., who is, from the get-go, not willing or open to being there. When we learn that her character is actually a rich bitch—more specifically, the daughter of Lumon’s CEO, James Eagen (Michael Siberry)—this hyper-reluctance to “embracing the work” compared to the others makes all the sense in the world. For rich people rarely feel they should be doing menial labor (whether physical toil or “mental” office bullshit). In other words, Helly basically possesses the Claire in The Breakfast Club philosophy of, “Excuse me sir? I think there’s been a mistake. I know it’s detention, but, um, I don’t think I belong in here.”

Unfortunately, her “outie” believes otherwise, at one point directly speaking to her through a pre-taped video and reminding Innie Helly that she is the slave (not even an “actual” human, as far as Outie Helly is concerned) with no power in this scenario, and that “Helly R.” will do exactly as she’s asked. What choice does she have, after all? The words of Wells’ Time Traveler echo the foreboding response, “Ages ago, thousands of generations ago, man had thrust his brother man out of the ease and the sunshine. And now that brother was coming back—changed!” Helly is the catalyst for that change as she incites something in Mark beyond what Petey has with his sudden appearance, and then, death. He is also changed by witnessing Helly’s dogged pursuit of freedom by any risk or means necessary, as Dylan and Irving will be by the end of the season. The entire quartet suddenly outraged enough by what’s been done to them by their “fellow” man (but it’s worse because, like Radiohead sang, “You do it to yourself/It’s true/And that’s what really hurts”).

The Time Traveler happening upon the disgruntled “innies” of the world might make the same remark as he did of the Morlocks (in their connection to the Eloi): “…the mere memory of Man as I knew him had been swept out of existence. Instead were these frail creatures who had forgotten their high ancestry, and the white Things of which I went in terror. Then I thought of the Great Fear that was between the two species…” Indeed, the outie fears the innie far more because they know on some level that what they’ve done is cruel and inhumane. Creating a very incestuous type of caste system that only something as nefarious as technology (in collaboration with a corporation-government alliance) could furnish.

For it’s easy to prey upon the masses knowing that most individuals would simply love to send a different “half” of themselves to do their “dirty bidding” in the hours that require one to work for no amount of money that could ever compensate a working-class person for the time lost. In this sense, Severance deftly highlights that slavery never truly went away—it’s just become more “civilized.” Otherwise, why would so many people despise working? Well, obviously it’s because most people don’t get paid to do things they enjoy. So why not, at the very least, be incognizant for the bulk of one’s day that is taken up by the tedious, inane worries of work?

To delight in such an option, from the perspective of the outies, is tantamount to how The Time Traveler illustrates his initial assessment of humanity based on his first run-in with the Eloi: “We are kept keen on the grindstone of pain and necessity, and, it seemed to me, that here was that hateful grindstone broken at last!” Well, maybe for some. But as usual, there is at least one-half of humanity who must suffer and sacrifice for the other half (*cough cough* one percent) to live in comfort and contentedness.