The Whale wastes no time in cutting to the quick of human desperation and sadness. As most stage plays tend to do. And yes, the film is based on Samuel D. Hunter’s 2012 play of the same name. Hunter, who adapted the script for Darren Aronofsky’s directing pleasure, accordingly leaves the one-location setting intact. A static milieu that is rendered totally believable by Charlie’s (Brendan Fraser) reclusive nature. Not necessarily because it’s a “conscious choice,” so much as a practical one. After all, he’s too morbidly obese to get very far without extreme difficulty and over-exertion. So it is that, with the help of his best friend/enabler, Liz (Hong Chau), Charlie manages to work and live with relative “ease,” at least considering his situation. One that finds him in the John Popper-from-Blues Traveler position of being too obese to masturbate without the risk of a heart attack. Which is where we find him within the first few seconds of the movie, and how the appearance of a missionary named Thomas (Ty Simpkins) at his doorstep is actually welcomed as Charlie tussles with the throes of death.

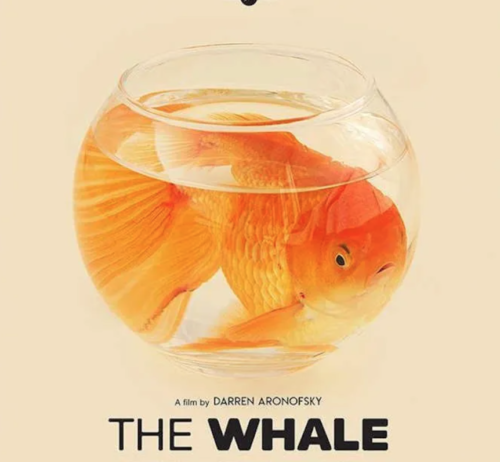

To calm and recenter him, Charlie insists that Thomas read from an essay he hands to him about Moby-Dick, one that we later find out was written by his estranged daughter, Ellie (Sadie Sink), and that he has become rather obsessed with for its “honesty.” Having written it in eighth grade (the audience is expected to suspend disbelief on such a book being assigned at that age), the sentence structure is simple and written in the first person, with Charlie most focused on the lines, “…and I felt saddest of all when I read the boring chapters that were only descriptions of whales, because I knew that the author was just trying to save us from his own sad story, just for a little while.” That author being Ishmael who “shar[es] a bed with a man named Queequeg,” as Ellie homoerotically phrases it. Indeed, there are a number of scholars who interpret the relationship between Ishmael and Queequeg as homoerotic, with one critic, Caleb Crain, noting that the cannibalism portrayed by Herman Melville is meant to be a metaphor for homosexuality. Charlie’s guilt-racked gay relationship and subsequent practice of “eating himself to death” fits in quite nicely with that analysis of Melville’s opus—the subject of which also ties in to the film not just title-wise, but “pursuit”-wise as well. With Captain Ahab easily representing the religious zealots embodied by Thomas and the “New Life Church” he works for seeing “The Whale” as pure evil (in this case, Charlie—because of his homosexuality). Just for existing, for being itself. As Charlie is, obese or not.

“Working around” the physical limitations of his body, Charlie’s job as an English Composition professor teaching courses for an online university also allows him to conceal the monstrosity he has become. To address the word “monstrosity,” the backlash against The Whale for its portrayal of corpulent people was rebuffed by Aronofsky, who worked with the Obesity Action Coalition not just to help Fraser with the physicality of the role, but to better get into the headspace of the self-destruction and addiction behind overeating. Per Aronofsky, the Coalition “really [feels] this is going to open up people’s eyes. You gotta remember, people in this community, they get judged by doctors when they go to get medical help. They get judged everywhere they go on the planet, by most people. This film shows that, like everyone, we are all human and that we are all good and bad and flawed and hopeful and joyful and sorrowful, and there’s all different colors inside of us.”

Aronofsky also added of the decision to cast a “thin person in a fat suit” (see also: Weird Al’s “Fat” video), “…actors have been using makeup since the beginning of acting—that’s one of their tools. And the lengths we went to portray the realism of the makeup has never been done before.” Those lengths furnished by makeup artist Adrien Morot, who was rightly nominated for an Oscar for her part in bringing the character of Charlie to (large) life. His “girth,” of course, serves as the pronounced metaphor regarding how self-flagellation comes in all forms—“shapes and sizes,” if one prefers a more overt pun. And Charlie’s has been to eat himself into oblivion as punishment. Not just because he feels partly responsible for the suicide of his long-time partner, Alan, but because he left his wife, Mary (Samantha Morton), and then eight-year-old daughter to be with him. At the time of their meeting—when Alan was a student of his at night school—Charlie was still “robust” in build, but obviously not morbidly obese. And whatever Alan saw in Charlie was less about looks and more about his personality. His essential “goodness.” For it’s true what they say about the person who loves you being able to see past certain physical “flaws” that others might deem “grotesque.” But Charlie is bound to live forever with the guilt of abandoning his daughter. Something he’s determined to make right as best as he can.

This is spurred by the imminence of his demise, as the film commences on Monday to show us the short lifespan of a week Charlie has left after being told by Liz (who is, conveniently, also a nurse) that he has congestive heart failure. Rather than seeking medical treatment—which plays into not only a lack of health insurance, but the aforementioned fear of judgment by a medical professional—he decides to “get his ducks in a row,” as it were. And at the top of that list is getting to know Ellie and trying to help her. When she refuses to stay after being summoned over, he offers to pay her all the money he has—roughly $120,000 in his bank account (all of which he has saved up specifically to give to her). By this point, the “uniquely American” nature of the tale has been accented not only by the out-of-control overweightness that a person can allow to flourish in their dissatisfaction paired with endless access to processed foods, but by the fact that only in America would someone rather die than go to a hospital and incur the inevitable hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of debt as a consequence. This always occurring when one doesn’t pay the monthly baseline cost of health insurance (itself an extreme expense for those who can’t get it at least partially covered by their workplace). What’s more, only in America would someone be so concerned with expressing their love through money. And know full well that love can be “bought.” Or at least the feigning of love. Which Ellie does little to convey through her surly, enraged aura.

An anger that has led her to alienate others from being her friend at school, as well as any teachers who might want to keep her from failing out of it. To that end, part of the deal to get Ellie to keep coming around while he still has time is that he’ll rewrite some of her essays for her. In exchange (as he’s convinced of her brilliance), Charlie asks Ellie to write whatever she wants in the notebook he provides for her while she comes over to his apartment. After the first “session,” he finds that all she has written is: “His apartment stinks/This notebook is retarded/I hate everyone.” But yes, it’s a haiku. So she isn’t the incompetent git that her teachers say she is.

Taking into account the religious and faith-based overtones of the movie, the biblical narrative of Jonah and The Whale provides an additional symbolic context. For Jonah was saved from drowning by a “whale” (or big fish), which one can argue Charlie has done for Ellie by reminding her of her greatness. That she’s “perfect”—just as she is, as Mark Darcy would say. And as it’s the last meaningful thing he can do as a human being on this Earth, he’s made it his mission to not be foiled by her armor. Her dogged determination to be as mean and vicious as possible. For he knows, in the end, that people are “incapable of not caring” (save for, you know, people like Putin). That belief certainly holds true for Ellie.

As for Liz, who learned long ago by trying to “save” her brother, Alan (hence her deep connection with Charlie), she does not believe a person can ultimately be “saved” by anyone but themselves (going inherently against everything Christians stand for). This being what keeps her from intervening in what Charlie truly wants: the long punishment on his body he’s given himself, followed by death. What Thomas believes Alan was striving for in order to make himself “clean” again for God, citing a scripture Alan had highlighted in his own bible about separating the spirit from the flesh—flesh, in all its meanings, being at the very center of The Whale. But so is strength. The ability for the mind to overpower the body in ways both harmful and beneficial. This being why it was so appropriate for Fraser to note of the part, “I learned quickly that it takes an incredibly strong person inside that body to be that person. That seemed fitting and poetic and practical to me, all at once.”

A whale isn’t the only symbolic creature in the movie though. There’s also the unacknowledged bird that Charlie keeps luring back to his window by setting food out for it on a plate. By the third act, that plate is broken into shards and the bird seems nowhere to be found. Charlie’s own proverbial plate has been broken now, too, as there’s nothing left to figuratively eat. He’s swallowed life whole and it has spat him back into the abyss. In other words, this bird has flown.

[…] Genna Rivieccio Source link […]