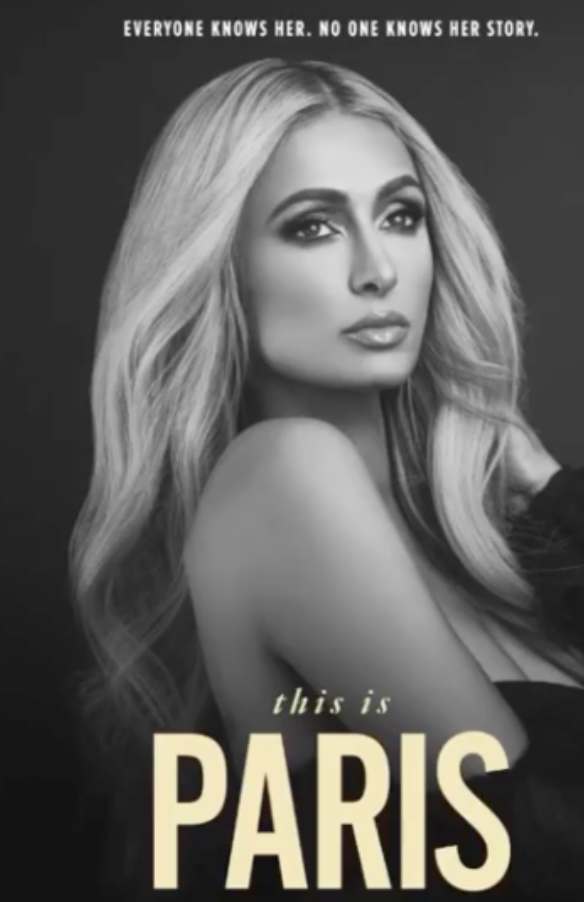

If you asked anyone their immediate perception of Paris Hilton, they would either blink at you absently like you’re insane and pretend they haven’t thought of her in years or tell you she’s a vacuous rich bitch. It is primarily this latter perception that Hilton herself has worked to cultivate. For as any shrewd woman will tell you, playing dumb is the best way to get ahead while everyone (particularly men) is underestimating and overlooking you. For Paris, with her congenital wealth and cookie cutter good looks (minus the lazy eye), getting a leg up on that front was easy enough, and yet she didn’t have to work or push herself to create an empire in her own right. She could have coasted on the publicity of being a “good time girl” in her teens and twenties, spending some of the family fortune for her full-time partying job. Instead, she parlayed that tabloid fame into something still entirely novel at the time: reality TV. With The Osbournes and The Anna Nicole Show being the only other real blueprint (after premiering on MTV in March 2002 and E! in August 2002, respectively) for “famous” people doing a reality show, The Simple Life one-upped the prototype by further blending more heavy-handed acting with “reality.”

Yet, at the time, everyone was quick and eager to believe Paris was as much of a dumb blonde as she projected herself to be. With Adria Petty’s (more known for her music videos than any feature films) 2008 documentary Paris, Not France, the intent to rebrand Paris within her brand was already brewing. A means to acknowledge that the dumb blonde shtick wasn’t going to have longevity unless Paris claimed it as a stylized version of the public’s preconceived notions about her. The kernels of This Is Paris lie within this one hour (and eight minutes, if not aired on MTV) glimpse into mid-00s Paris’ life. Not so different from what it is now, minus the fact that her sister, Nicky, grew out of making such public appearances long ago, particularly after getting married to James Rothschild, son of Amschel Rothschild—a mack daddy British banker and carrier of the legacy of the long-standing “prestige” of the Rothschild name, that is, before he hanged himself in Paris (somewhat ironically) in 1996. Marrying into a family with such a, shall we say, stodgy history undeniably meant Nicky had to button down a bit more and embrace the conservative Roman Catholic values she grew up loathing. Though not, ostensibly, as much as Paris, who began to rebel noticeably from the age of thirteen to fifteen when she discovered the nightlife of 90s New York. A sort of modern Edie Sedgwick (though the comparison seems rarely made), she filled a void in the socialite vacuum that had been lacking luster and vibrancy since the days Sedgwick came along in the 60s. The daily rags of NYC were quick to take notice.

Later on, as the 00s dawned, her basking in the spotlight was (retrospectively) a study in Psych 101 of Fame Seeking, stemming from an intense desire to feel love. To feel that people cared about her. In the beginning, it was easy to mistake the feeding frenzy (filled with paparazzi piranhas) for that sentiment. The one that had gone missing during her formative teenage years when her parents, Kathy and Rick Hilton, decided to banish her from New York City after she became a little too enchanted with the club scene (thanks to the best fake ID money could buy). Like Alice going down the rabbit hole, Paris suddenly felt she was her most accepted and authentic self within this alternate universe of clubland. It was here, undeniably, that her ardor for DJing would be born. Having gravitated toward the fashion world, Hilton signed a modeling contract (though the name behind that contract is markedly missing: Donald Trump and his Trump Model Management—because why wouldn’t a man who believes in the mantra “grab ‘em by the pussy” have his own stable of models?). Much to the extreme dismay of her strict and conservative mother, Kathy. Having herself been a child actor and model (à la Paris nemesis Lindsay Lohan), she wanted her eldest daughter to take a different path. One that was more “respectable,” perhaps. Contrastingly, her grandmother—a major influence, as noted in Paris, Not France as well—had always imbued her with the sense that she could be a glamorous actress based on her looks alone. That she had an “it” quality most could only dream of.

As Hilton stated, “My grandmother always called me Grace Kelly. Marilyn Monroe. And I wanted to live up to that for her.” Difficult to do when millions of people have watched you getting railed on the internet (though the same probably would’ve happened to Marilyn after she got famous if the internet had been around at the time). By this token, Hilton selecting Alexandra Dean (going by Haggiag Dean in the credits) to document the story makes sense when considering her prior film credit is Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story. Lamarr, too, had a persona that was misconstrued, never acknowledged for her intelligence or inventor chops (having contributed to the invention of spread spectrum technology during WWII). Hilton’s affinity for Old Hollywood also ties in with Dean’s previous documentary, being that the era was all about putting on a facade. Sweeping all unpleasantness under the rug (along with more than a few “dolls”), which was clearly learned behavior from her own repressive and repressed parents (her father would not even appear in the documentary, though he did for Paris, Not France).

In this germinal, still censored version of Paris in the 2008 doc, she established, “I wanna find out who I am. I know who I am, but I really don’t.” In part because it’s almost impossible to address who you are without addressing what you’ve been through. But even back then, she was glomming onto the “this isn’t me” mantra, stating she had donned the persona of Paris Hilton as a character for The Simple Life.

Her need to maintain a childlike persona, complete with baby voice, is an additional habit to note in Paris, Not France when understanding the root cause of this regression as a defense mechanism in This Is Paris. In the former documentary, it is while in a branding meeting with a board room filled with white men discussing the attributes of her brand that she herself tells them to add “childlike” to the corporate diagram that bottles her into a marketing strategy.” They conclude, “Innocence, that’s perfect.” The need for Paris to cling to this self-perception—and spread it to others’ view of her—of being a little girl is not unlike the Michael Jackson syndrome in which having one’s childhood experience ripped from them results in their need to spend the rest of their life trying to recreate it (though Hilton never saw fit to “become” a child by molesting them). “I think little girls like me ‘cause I’m still like a kid at heart. Like I just feel like a kid still. I don’t wanna grow up,” Paris muses. Of course, wanting to remain a child is part of the protective layer she’s put over herself to remember a time before things became so tainted, so irrevocably cartoonish and fucked up. It’s likely also part of the reason Paris has never come close to having any children of her own (though she’s sure to mention she’s had her eggs frozen in case she ever wants to have that daughter named London). Because, as it is said, you can’t really become a full-fledged adult if you never have kids.

In the midst of engaging in another interview blitzkrieg with the press while in Asia in Paris, Not France, someone says, “Tell us the best day of your life.” “The day I turned eighteen,” she tells the interviewer without hesitating. As we come to apprehend in This Is Paris, there’s a reason for this that had nothing to do with being able to buy a pack of cigarettes. Rather, because it meant total freedom, once and for all. It meant that all the power and control over her life was now legally hers. That no one could ever dictate any decision or route. Her thirst for making money, too, is a product of wanting to be as empowered as possible. For who could know better than a member of the Hilton dynasty that money is power?

Paris’ bouts with insomnia as a means to avoid dreaming are strongly conveyed in This Is Paris, whereas the problem is only casually alluded to in Paris, Not France as she offers, “Some dreams are really scary I have.” Without knowing the true “why” behind that, most would assume it was garden variety paparazzi nightmares. Elliott Mintz, her “crisis manager” a.k.a. publicist at the time, seemed to believe she was built for this kind of fame. However, it’s clear Paris already knew long ago that transforming herself into a brain-dead character was the best way to fully adopt numbness as she comments, “I feel like if I did really hurt as much as I should, I would go crazy.”

Her trust issues have only augmented in the years since this revelation, though she already realized in 2008, “I’ll never really find anyone that I could be with because it’s just spectacle.” And in This Is Paris, her short-lived boyfriend, Aleks Novakovic, proves the extent of how hard it is for her to trust men (evidenced by her setting up a hidden camera in her house so she can see if he does anything untoward while staying there in her absence). It’s a lack of trust that’s been proven well-founded time and time again (ahem, the sex tape), and it all ballooned out of a single night in her teens when she was taken away against her will and without being previously informed before being sent to Provo Canyon School. Provo, Utah, for those who aren’t Mormon and weren’t automatically aware what state the town is in.

With Dean slowly unveiling the revelation, she presents it slowly to Paris’ mother, just as she does to the audience. In discussing her take on Paris as an unruly teen, like a true Republican, Kathy explained of her decision to send Paris away, “Fear, to me, is the most powerful feeling there is.” Fear she would get abducted, fear she would get sexually assaulted, fear she would tarnish the family name with her antics. Thus, she was banished. And it wasn’t a boarding school of the Institut Le Rosey caliber (even though that joint has come under fire recently as well for its reputation of allowing bullying). No, it was physical, verbal, mental abuse all day, every day. Paired with the Girl, Interrupted meets One Flew Under the Cuckoo’s Nest flourish of making each “student” take a batch of unidentified pills every day. Pills that Paris learned how not to swallow, leading her to be punished with double-digit hours in solitary confinement stripped of her clothing. While trapped inside this hole (overhearing a more crazed teen in the cell next to her screaming in a straightjacket style), Paris retreated into her mind, fantasizing about what she would do and who she would be when she got out. It was during these “astral projections,” if you will, that the notion of this character was first developed. Someone bubbly, happy and problem-free.

“I love making money,” she tells Nicky at one point in response to not wanting to ever take a vacation. After all, it would detract from her new life goal of making a billion dollars (once upon a time, millions would have sufficed). And the undisputed amount of liberty that comes with being in such a financial tier.

But the pressure of sustaining this character and where she was born from clearly starts to weigh too heavily by the end of This Is Paris. There’s a moment in her closet when she sheds all traces of the veneer and admits everything is bullshit (maybe even the documentary). “I don’t give a fuck about any of these things,” she declares of the shoes and the accessories. All they served to do was feed the character that has made her millions. Yet how could she turn her back on that version of herself entirely, even if occasionally vacillating between the schizophrenic habit of speaking normally and with her baby voice?

Finally confessing to her mother what she endured (though perhaps not getting the severity of the trauma across as well as she did while among her fellow survivors), Kathy has something of a plastic surgery reaction (meaning expressionless) and says, “Had I known this, you know that Dad and I would’ve been there in one second.” It does little to vindicate what happened. Nor does the fact that when Dean asks Paris at the end, “Can you and ‘the brand’ have a divorce now?” she reverts to her baby voice to insist, “No. It’d be an expensive divorce.” Dean presses, “You can’t do this brand forever. You’re gonna age out of it.” She smiles, shaking her head, “No. I’ll just be like this forever.” Cue Frally’s version of “Girls Just Want To Have Fun” (though when it comes to covers of this track, no one beats The Chromatics—what, Paris couldn’t afford it?). Redemption narrowly missed.