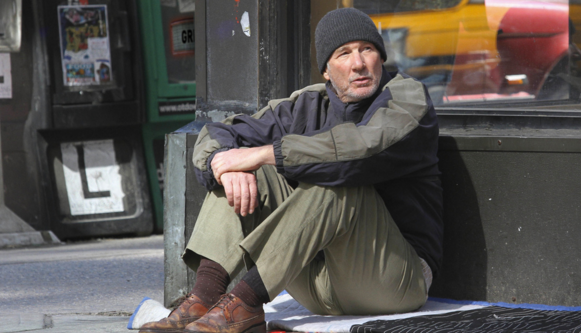

For a population often overlooked or simply ignored, Oren Moverman’s Time Out of Mind offers at least some modicum of respect and empathy to the homeless–specifically those subjected to the rough-hewn lifestyle of New York. The drawback, of course, is that it is told through the somewhat sanitized lens of a formerly middle class white man named George (Richard Gere).

Our introduction to George comes at the same time as Art’s (Steve Buscemi), a building manager who comes into an apartment with his crew to do some maintenance. As he enters the bathroom, he stumbles upon George, groggy and seeming to have incurred a head injury, but insistent that a woman named Sheila lives there and has given him permission to stay, but it’s clear “Sheila” seems to have been evicted some time ago.

Back onto the unforgiving streets, George tries to find shelter in the form of a bench that can briefly offer him the solace of sleep, but is plagued by the noises of assorted drunks and hucksters, one of which throws a shoe at him, which he later puts on. He then gives the fake story to a pair of passersby that someone stole his wallet and he just needs enough money for a MetroCard. This secures him a place to sleep for the night as he rides back and forth on the train, just as you often see happen when you’re coming back from your own drunken escapades.

Throughout his travails–being ignored, having nowhere to go, getting treated like a parasite–George remains in denial about his situation. He doesn’t begin to have a revelation about what’s really happened to him until he’s left no other option but to check into a South Williamsburg shelter, where he is forced to answer some harrowingly personal questions about his life, including making mention of his daughter, Maggie (Jena Malone, in a sparse role). We’ve seen the sheepishness of his roundabout interaction with her previously, during which he gives a man smoking a cigarette outside of the bar she works at some childhood photos to pass along to her.

Evidently, his past behavior as a father is, in part, what led him–in a simple twist of fate that could happen to anyone, regardless of race–to homelessness. Too far gone down the path of error, George suddenly has the epiphany, “I don’t exist!” when he can’t secure any form of documentation that proves his identity: social security card, birth certificate, etc. Because each form of identification requires another, he feels caught in the vacuum of bureaucracy, which two cast members from Orange is the New Black exist in.

In between trying to pick up the pieces, George re-encounters the woman he feels is Sheila, though her name is actually Karen (Kyra Sedgwick), and ends up answering that question we all secretly wonder about homeless people: yes, they do fuck upon occasion.

With each “rocky” incident George encounters, however, one can’t help but wonder how much more daunting the challenges are for a non-white, far less well-groomed (Lucille Ball in Stone Pillow he is not) homeless person might be. This is one of the cruxes of the problem with Time Out of Mind: its narrowness in scope–which Overman probably assumed would make it a stronger film. Instead, it gets rather washed out among all the other movies about poverty in New York. But, on the plus side, at least the layman’s awareness is raised by watching this and getting a more “humanistic” look at those with very scant viable choices.