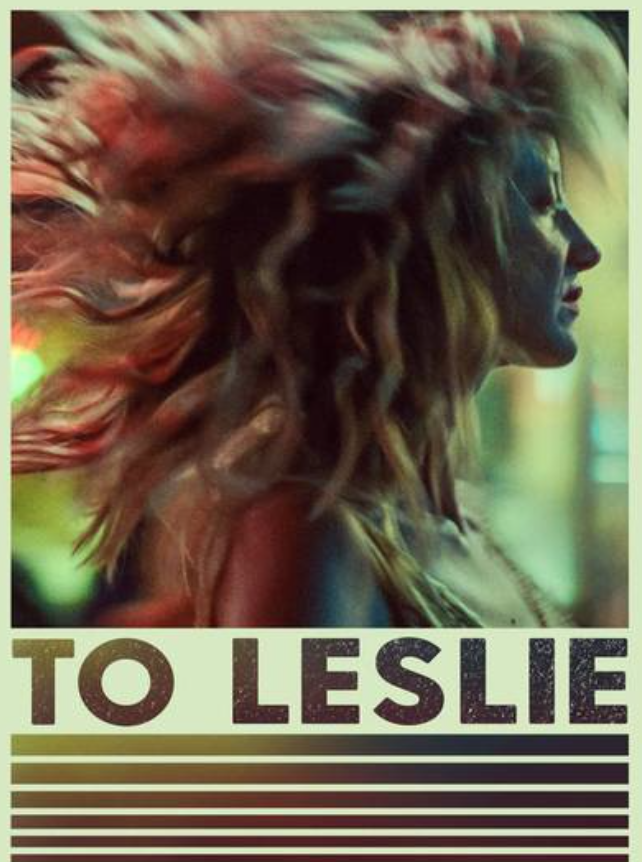

As Vivian Ward in Pretty Woman once said, “People put you down enough, you start to believe it.” That statement couldn’t be any truer for washed-up alcoholic Leslie Rowlands (Andrea Riseborough), a proverbial small-town girl whose only achievement in life has been winning the lottery at her favorite local bar in West Texas. Although only a “modest sum” of $190,000, it’s enough to make Leslie’s head get a little too big as she proceeds to party the funds away. All while her parents, thirteen-year-old son, James (later played by Owen Teague), and sister, Nancy (Allison Janney), watch.

It is the latter and her husband, Dutch (Stephen Root), who end up helping raise James when Leslie decides to leave “just so you can go out drinkin’ [and] thinkin’ you’re hot shit,” as Nancy puts it. Of course, anyone who has been an alcoholic or known one is aware of the seduction that the bottle holds. And it’s far greater than the appeal of being a Responsible Adult. Which is why, at the time, Leslie doesn’t feel so bad about the abandonment, sinking deeper and deeper into her hole of addiction and financial ruin. As she confesses to her employer-turned-semi-boyfriend/custodian, Sweeney (Marc Maron), “I was happy to have a break, okay? I partied and I didn’t mean to spend it all. I lost everything and I had to file for bankruptcy. So yeah, I left him.”

Leslie’s explanation cuts to the core of Ernest Hemingway’s iconic dialogue from The Sun Also Rises: “‘How did you go bankrupt?’ Bill asked. ‘Two ways,’ Mike said. ‘Gradually, then suddenly.’” And when you’re “flush,” everyone around you wants to cash in on it as well, which is precisely what happened with Leslie, as she undoubtedly ordered rounds for everyone in the bar each time she went out. And, to the point of Nancy mocking her for thinking she was “hot shit,” Leslie still seems to be laboring under that misconception while she shamelessly flirts with men at bars to attempt getting her tab covered in her present state of broke assery.

Ten years ago, it might have worked, but in the now, she’s become the proverbial “sad bar troll.” The one who stayed at the fair too long and currently looks like a bedraggled carny. And, talking of carnies, screenwriter Ryan Binaco (whose only previous writing credit is 3022) seems to want to emulate the message of William Lindsay Gresham’s Nightmare Alley (another lurid tale about an alcoholic hitting rock bottom after experiencing life at “the top”). A novel (and movie) that reiterates to the “little people” that they should be happy with their lot in life before they go trying to reach for the stars. To Leslie does something similar, being that Leslie is a woman determined to believe that the money will change her and her son’s lot in life. But, as Somen a.k.a. Steve’s mom in Welcome to Chippendales warns, “Some people are not meant to be rich.” For when you’re born fundamentally “gauche” (see also: The Beverly Hillbillies), you’ll only end up either 1) squandering it all or 2) constantly wanting more—never “just” being satisfied with the fluke of a come-up you’ve already gotten.

In Leslie’s case, it’s the former category, and she pays a much higher price for ever having been “rich” in the first place—a heavenly blip in time that hardly compares to the hell she’s expected to spend the rest of her life in now—than she would have if she had gone on as an “ordinary” woman. That is to say, someone who kept their head down and kept working some banal job without letting “grand” ideas of being wealthy get the better of them. Even though we live in a society that preys on this naïve hope of the plebes every day (*cough cough* the very existence of the lottery and its nonstop barrage of ads peddling notions of hitting the big time with no effort except the purchase of a ticket). It’s also sometimes better known as capitalism.

And once Leslie loses all her money, she also loses her entire sense of worth. Something that Sweeney, who manages the cheap roadside motel that his friend, Royal (Andre Royo), owns, has to help remind Leslie of as she makes slow progress on getting sober and actually doing the job she was hired for: cleaning the rooms. But, to bring up something else the aforementioned Vivian Ward said, “The bad stuff is easier to believe. Ever notice that?” It would be difficult for Leslie not to, what with all the “townfolk” constantly talking about what a fuck-up she is. But Sweeney tells her point-blank, “You’re not the piece of shit that everybody says you are.” In this regard, To Leslie additionally emphasizes that sometimes it only takes one person to believe in you in order for you to believe in yourself again. Just as it was for Vivian with Edward in Pretty Woman. And yeah, Leslie would probably be prostituting herself if there was more male interest actually shown in the “product.”

Instead, she accepts the only job she’s miraculously offered: hotel maid. And all because Sweeney sees her homeless, drunken state and takes pity on her. Only to return his charity by later seething, while sober, “I’m fuckin’ stuck here with you and Royal—a pair of fuckin’ hilljacks like the shit icing on my shit fuckin’ life.” Sweeney reminds, “Me and Royal are the best thing that happened to you. So don’t call us names. And your family won’t talk to you because they shouldn’t after what you did. But you’re livin’, right?” She bursts out laughing at the “consolation” as he continues, “I’m sorry it ain’t a fairy tale, we all shoulda done things differently. But you’re what’s wrong with your life, not anyone else.”

Royal expresses a similar sentiment when he tells Leslie at a town gathering, “Now everyone thinks they should be livin’ some life out the movies. Life is hard. Stop actin’ like it ain’t.” But even To Leslie, for all its bleakness, cannot fully surrender to giving its anti-heroine a totally dreary ending. Even if it might seem that way by Hollywood standards, with The Hollywood Reporter praising, “Recalls the grit of 1970s American indie cinema at its most indelible.” Yet, if that were an accurate comparison, somebody would end up either dead or heartbroken (e.g., Looking For Mr. Goodbar and Five Easy Pieces, respectively). Neither of which happens in To Leslie, a film that ultimately wants to declare to the masses that it’s okay to just be “ordinary.” To have modest dreams instead of lofty visions of fame and fortune. An assurance that probably means nothing in this world of “viral fame”-seeking whores who will have to learn the hard way that capitalism only favors a plebeian “come-up” for so long before cutting them down to size again.

[…] Genna Rivieccio Source link […]

[…] to well-known members of the Hollywood elite touting the performance of Andrea Riseborough in To Leslie. That “campaign” (which cost literally nothing next to the monetary amount required for […]

[…] to well-known members of the Hollywood elite touting the performance of Andrea Riseborough in To Leslie. That “campaign” (which cost literally nothing next to the monetary amount required for the ad […]