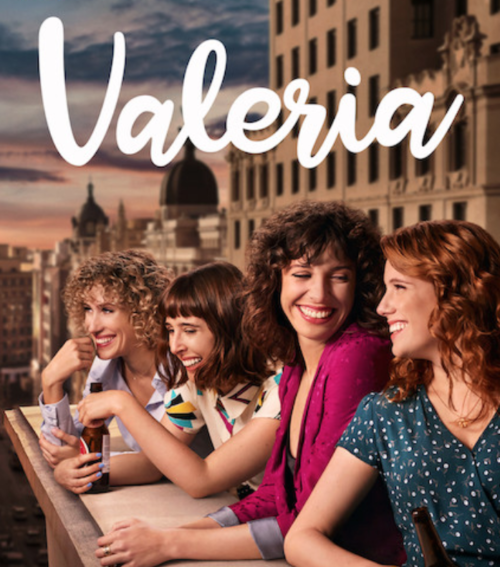

On the heels of Netflix’s latest Spanish hit (following Cable Girls), Valeria, the barrage of comparisons to Sex and the City have come in ad nauseam. And whether or not the creator of the show, María López Castaño, cares about the parallels, or did it as a deliberate means to attract an international audience, it has to be said that there are far more nuances to this show about four friends navigating their careers and love lives in Madrid. For starters, the eponymous Valeria (Diana Gómez)–the Carrie Bradshaw of the outfit–is married, which automatically reduces her “fabulosity” quotient when it comes to being young and untied to anyone in the “big city.”

That her husband, Adrián (Ibrahim Al Shami J.), is aloof to her dreams and uninterested in her writing career shows just how much the two fell prey to the whimsy of their young love, seemingly having gotten married when Valeria was twenty-two and only freshly arrived to Madrid from Valencia. Now that’s some shit Carrie would never pull, preferring instead to get an abortion at the first sign of being tied to any one man at such a young age. Still, it doesn’t stop the writers from developing a forbidden love triangle, completed by Victor (Maxi Iglesias), a friend of Valeria’s bestie, Lola (Silma López). Lola herself is the “Samantha” of the quartet, free-wheeling and promiscuous, so she claims. Her determination to never need any man for something other than sex stems, obviously, from being abandoned by her mother during her adolescence. So she opts for the sexual satisfaction of a married man named Sergio (Aitor Luna), which is what keeps her from meeting up with Valeria one night at a party she insists on going to. Their supporting Charlotte and Miranda friends, Carmen (Paula Malia) and Nerea (Teresa Riott), respectively, also come up with their reasons for not showing up, leaving Valeria to engage with the charismatic Victor the entire night.

As she tells him her struggles with coming up with an adequate storyline for a manuscript she’s expected to turn into her publisher imminently, she realizes Adri has never listened to her like this. Jokingly calling her “Impostor,” she reciprocates with the nickname “Dick.” It’s all very sweet, and clearly building up to a dangerous attraction. Valeria is further pushed to question what she’s allowed her life to become, and if it’s the best choice for a writer in search of inspiration and in need of being encouraged for her dreamer tendencies. She’s even willing to break the “covenant” of marriage if it means finally finding the “muse” she needs to finish her book. And, as we all know, even Carrie B. wouldn’t dare fuck with a married man until she had already fallen for him when he was single. Valeria, in contrast, doesn’t seem as committed to respecting the legal aspects of fidelity when marriage is involved, increasingly crossing the lines of appropriateness with Victor. The man who also advises her not to settle for taking a boring security guard job at a museum when she would feel so much better about herself if she just kept writing.

Adri, instead, keeps hounding her about how the interview went, not even trying to hide his desperation as he reminds her that they need the money. When she takes the risk on turning down the job, it doesn’t pay off–her manuscript essentially laughed at by her publisher who tells her she’s not ready for the big leagues. When she confronts Adri after her day of rejection, he kicks her while she’s down to scream, “I’m just sick of things never working for you!” These are all things that, of course, would never happen in Carrie Bradshaw’s universe–for no one would ever dare shake her out of her delusional reverie, least of all when it came to telling her that her writing is schlock.

Valeria, too, is writing about sex, but not for a column, and not for distribution in some rag that will be tossed out the same day. No, she’s decided on an erotic novel that will have far more class than E.L. James. The problem is, there is absolutely no sexual chemistry in her marriage for her to draw from. Which is perhaps why she starts to succumb to Victor’s overt flirtations both over the phone and in person. Despite this, she’s now vowed to give up on writing, telling her friends she’s surrendered to her fate as “guardian of the rock” in the museum… a rock she’s named Antonio.

As Madrid experiences a heatwave in episode three, “Alaska,” one can’t help but think of SATC’s season three episode, “Hot Child in the City,” in which one of NY’s own infamous summer days suffocates all with its rays. Except instead of glamorizing the perks of childhood and youth (which is essentially what the entire series does beyond this episode), “Alaska” deeply contrasts the difference between a narrative about sex taking place in capitalistic mutant New York versus Madrid. The conversations seem less cursory, less obsessed with fashion labels and economic status–in short, less la-di-da. Plus, at least Nerea is a lesbian instead of briefly posing as one like Miranda, offering some much needed sexual diversity.

It is perhaps because of her frustrations with having to keep her sexuality a secret from her parents that Nerea loses her temper in a conversation about #MeToo with Juan (Fernando González), the only male friend to join them at any point for drinks in the middle of the day (also something that would be frowned upon in NY). That #MeToo wasn’t ever broached even before it was “a thing” on Sex and the City is, of course, telling of the show’s own complicity in perpetuating lies women were supposed to tell themselves about how men act. In this conversation, a discussion about women expecting men to be horny all the time leads Nerea to counter, “So ‘normal’ guys can’t keep it in their pants, but if we want it, we’re crazy?” Juan interjects, “Well I don’t get it. You’ve made it the total opposite with this whole fucking ‘me too’ thing. Now it’s cool to play the victim.” Nerea reminds, “We are victims.” Juan offers the classic male dispute, “I know, but why didn’t women report it before?” Lola chimes in, “What the fuck? Now you’re telling us when to report it?” Juan shrugs, “No, but not all the cases are true.” Nerea snaps, “Sure, because women love making this stuff up so everyone can judge us.” Juan reminds, “Since the dawn of time, producers have slept with actresses and no one said a word. Power is erotic.” Nerea insists, “No, that’s abuse of power.” Juan remains steadfast in his conviction with, “What the fuck are you talking about? Look, how many of you have fallen for or been into your boss? Or a professor?” Nerea shuts down his so-called argument with, “Fuck that. That’s you again. See? That’s the problem. We always have to justify everything we do. What about them? That teacher or boss? They’d never get those girls if it weren’t for their position of power. That’s fucked up. Screw someone who sees you as an equal, damn it! Or you’re a piece of shit.”

And that’s the great difference between a show like Valeria and its so-called template, SATC. The latter never illumined any such thinking despite categorizing itself as a visionary or progressive narrative for women when, in fact, the entire premise is one giant failing of the Bechdel test in which the quartet obsesses over ways to minimize themselves for the benefit of the men they’re interested in. A move that never makes a woman feel good about herself, which is why Carmen is the one to have the biggest identity crisis by the end of the eight-episode season–for she has decided to sacrifice her potential for career growth and advancement for the sake of her boyfriend and collaborator at work, Borja (Juanlu González), who, in turn, repays her by taking the job himself (granted, he didn’t know she had refused the offer to stay in the same position in order to keep working with him).

Ending on a cliffhanger that speaks to how the nature of publishing with the intent of mass sales works, we see that Valeria, unlike Carrie, has far more sensitivity about her writing than the latter ever did (only ever concerned with the superficial issue of how her book cover might look). Valeria’s attachment to her craft is something the show reveals to be a passion she’s held since childhood (see: the episode “Mr. Champi”), whereas with Carrie, it comes across as just another narcissistic outlet. A way for her to “make the scene” in New York before the advent of “content creation” took all credibility out of being a “writer” in that town. Were Carrie set in the NY of the present, there’s no doubt she would no longer even be a writer. Maybe a fashion influencer or a trend forecaster–any title that holds weight with the present brand of materialism and externality in New York. So no, do not reduce Valeria to being a “Spanish Sex and the City.” Because it has far more depth than that by sheer virtue alone of not being set in the U.S.’ primary bowel of self-obsession.