Some of Kostenbaum’s primary obsessions include Anna Moffo (“Anna Moffo’s Funeral”) and Brahms (“Notes on Affinity”)–though he’s at his best when talking about himself, Lana Turner or Susan Sontag. Overall, the cohesive motif throughout the book is that to create art is to evade total insanity. For instance, in the essay entitled “The Inner Life of the Palette Knife,” about artist Forrest Bess, Kostenbaum states,

“One of my pedagogical aims is to encourage writers, painters, sculptors, and performers to make work that resembles [Forrest] Bess’s, work that is modest, grandiose, peculiar, detailed, reduced, blunt, odd, a little bit stupid, a little bit clumsy, with secret pockets of refinement, as if an Albrecht Dürer were sleeping inside a Fauve.”

It is esoteric references like these blended with Kostenbaum’s impressive vocabulary that makes My 1980s so immensely engaging (unless, of course, you’re the type who doesn’t like to be reminded of how limited your pop culture and verbal lexicon is).

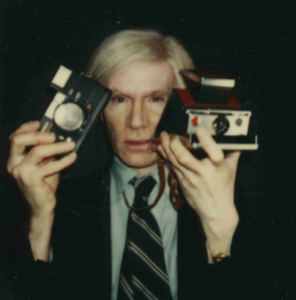

His predilection for espousing the artistry of the underdog is further illumined in the same essay with the assertion, “I’m also defending the right to be solitary, unpopular, and unbeheld. Bess needed solitude to make his art. Art justified his solitude, gave it dignity or purpose. Maybe half the reason someone becomes an artist–or the kind of artist that Bess became–is to experience uninterrupted solitude.” This statement rings true for anyone who has ever hated being among the masses and used art as a reason not to engage with them. Kostenbaum makes a similar analogy with regard to Andy Warhol’s ability to avoid actually conversing with anyone in his social circle or anyone interviewing him for a prolonged period. In the essay “Warhol’s Interviews,” he makes the astute observation, “Warhol, playing Houdini, escapes conversation’s captivity. His interviews perform a drag act of imprisonment within unsympathetic interlocution; in doing so, they paint a DayGlo exit sign that we would be well-advised, as Warhol’s acolytes and inheritors, to follow.”

In a similar vein, Kostenbaum views Debbie Harry, the muse that serves as his beckoning book cover, as a spokeswoman for tacit artistry. After seeing Harry at a supermarket in the early oos, Kostenbaum is reminded of her gender-bending ways–in and of itself a form of creative skill. He makes the appraisal, “Even her physical beauty seemed ironic; she seemed to deploy it as an analytical torch, a secret agent, dismantling the stereotypes she cheerfully traversed. In the Polaroid snapshots that Andy Warhol took of her in 1980, she gazes at him–and at the viewer–from across the moat of received wisdom, whose toxicity can’t touch her; with us, she exchanges a complicit glance, as if to say, ‘We understand the joke that gender is, and we understand how masterfully I embody its barbed glories.'”

In case you were wondering, Kostenbaum isn’t always quite so culturally pedantic in every essay. In fact, there are many playful moments in segments like “A Brief History or Reinvention,” in which he sizes up varying forms of reinvention with humorous calculations like, “Jesus reinvents Judaism. Duffy reinvents catchy naïveté.” Kostenbaum also has a tendency to get subtly sentimental about his catharsis, his end all, be all–writing. In “The Desire to Write,” he sums up his own style by saying, “The point of writing–of my writing at least–is to travel forward under the guise of traveling backward.” Indeed, this is the crux of My 1980s in choosing to evaluate artists, musicians and writers of a bygone era.

More than a gifted writer, Kostenbaum is a born cultural critic, whose knack for prose goes hand in hand with his ardent commentary. Regarding his first listening of Johannes Brahms’ “Piano Concerto No. 1 in D Minor,” Kostenbaum notes, “I understand the inability to pursue happiness, and I wanted to build a life around hiding from closure, from optimism, and from productivity. And so once again I played the LP of the first movement, to cement my affinity–but not to understand it.” But, try as he might, Kostenbaum seems to understand everything pop culture-related, no matter how arcane.

Perhaps it is Kostenbaum’s feminist side that shines through most of all in every composition. For instance, in the second essay of the book, “Heidegger’s Mistress,” Kostenbaum displays his female spirit with grandeur as he declares, “While writing this essay, I am reading Simone de Beauvoir’s Adieux: A Farewell to Sartre (in translation), and Iris Murdoch’s Sartre: Romantic Rationalist. I can take Sartre only from the woman’s angle.” His intrinsic ability to understand the female perspective is at its most manifest when he discusses his great love, Susan Sontag. The man essentially writes a treatise about her called “Susan Sontag, Cosmophage,” wherein he pronounces, “Sontag’s credo: Move on. The phrase comes from her grief-ennobled, expansive essay on her friend Roland Barthes: …The writer is the deputy of his own ego–of that self in perpetual flight before what is fixed before writing, as the mind is in perpetual flight from doctrine.” Apart from the meta nature of writing an essay about an essay, Kostenbaum, in addition, reveals yet another important stance on writing, one that is rarely acknowledged by others.

For those most allured by Kostenbaum’s time spent in the 80s, your best bet is reading the very first essay, “My 1980s.” In it, Kostenbaum writes in a random, stream of consciousness sort of manner that echoes the decadence and fun-loving nature of the 80s itself. Still, there are other essays that also make mention of the beloved decade, as with “Advice to the Young,” when he reminisces, “In 1985 I wore an Eiffel Tower earring to a Greenwich Village cafe, and thought myself sexually adventurous, though the earring hurt my earlobe, in winter: frostbite amidst unread Francis Bacon essays and a new consciousness that my genitals could be considered poison…” Everything about this screams, “I came of age in the 80s.” And if you don’t agree with Kostenbaum’s portrayal, well, it’s like he says, “If my eighties don’t match yours, chalk up the mismatch to the fact that I am profoundly out of touch with my time. I never chose to nominate myself as historical witness.”