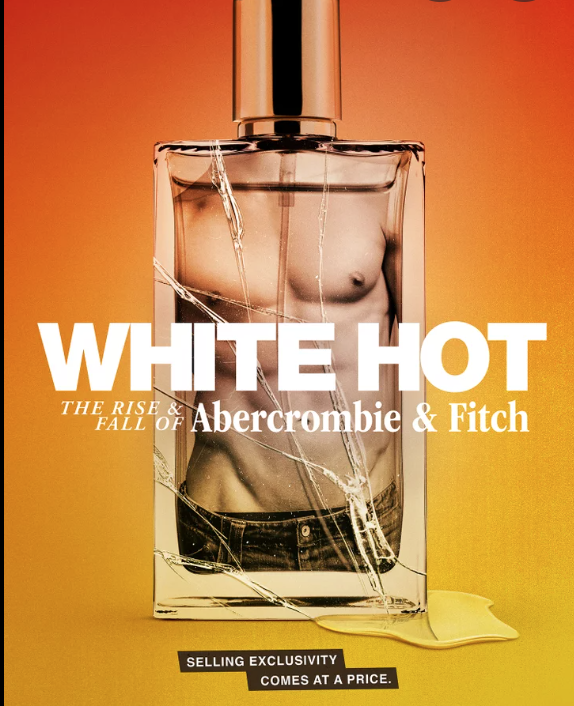

As one of the many offerings of late favoring 00s-based nostalgia, Senior Year shows its main character, Stephanie Conway (Rebel Wilson), waking up from a coma after twenty years to find herself in a whole new world from the one of her millennial youth. Determined to finish her senior year of high school regardless of her current age, she asks the students at a lunch table, “Where do the popular kids sit?” “We’re all popular,” one of the Gen Zers replies. “Oh no no no, there’s only like three ways to become popular: to be a cheerleader, to work at Abercrombie or to let guys go in the back door.” It is that second way to “be popular” that strikes a chord with the newly released documentary, White Hot: The Rise & Fall of Abercrombie & Fitch. Directed by Alison Klayman (who most recently brought us another nostalgia-centric documentary, Jagged), the focus of the narrative is primarily on the long-standing exclusionary practices of the brand. Practices, in fact, that are what made it so sought-after in the first place.

However, in addition to that emphasis, there is the other ironic piece of the puzzle in that both A&F’s former lead ad and catalogue photographer, Bruce Weber, and its erstwhile CEO, Mike Jeffries, are gay (the latter not coming out “officially” until 2013). Which is no shock to any gay man, especially those forced to live in repression during their teen years while being taunted with this type of Weber-curated imagery.

In the 00s, being gay was hardly as embraced—nay, “chic”—as it is now. The word itself being brandished by millennials as a term to mean “stupid” or, worse still, “retarded” (yes, you could say that “back then,” hence that Black Eyed Peas song). So no, it wasn’t an inviting atmosphere or era to be a gay man, least of all in the suburban malls where the chance of a run-in with any of the jocks proved nightmarish (see: Weird Science, one of the many mall clips shown in White Hot). But that didn’t mean those gay men in positions of power (no pun intended) couldn’t pull the wool over straight men’s eyes by providing the ultimate troll in the form of such blatantly homoerotic imagery. It was something almost tantamount to that Euphoria scene of Lexi Howard’s (Maude Apatow) play, Our Life, during which Nate’s (Jacob Elordi) character, played by Ethan (Austin Abrams), proceeds to engage with the locker room environment in the most blatantly homoerotic way—and to the tune of Bonnie Tyler’s “Holding Out for a Hero.” Seeing it presented that way, Nate goes absolutely ballistic. And yet, it was right in front of his face all along, just like the A&F ad campaigns. As well as their discriminatory actions.

But it was “a different time,” as the documentary’s interview subjects call out on multiple occasions. One before social media gave everyone a megaphone to say how they “really” felt about something. In the millennial heyday of youth, however, it wasn’t about the consumer getting what they “wanted,” so much as stores packaging clothes in a way that convinced teens that they actually did want what was being sold. “Dress this way or risk being terminally ‘uncool.’” That was the motto. And there were even stores provided for the “fringe” character who didn’t fit into the prep mold of A&F or “copycat” brands like American Eagle and Structure. Take, for obvious example, Hot Topic, which, of course, gets mentioned in the documentary. Designed for the “punk” or “goth” (by suburban standards), this was also the store that sold Pimpercrombie & Bitch shirts in defiance of its rival identity brand.

Indeed, A&F was an early precursor to the rampant forms of “identity politics” that would crop up as the twenty-first century progressed. Under a new guise called: “wokeness.” But anyway, it’s true that, as most of the interviewees point out without explicitly saying it, the 00s were a kind of Dark Age in many ways. Still rooted in the influence of baby boomer ideals and gender norms. Ones that Jeffries himself seemed to get fucked up by as he would spout rhetoric like, “Who the fuck are you designing for? Dykes on trikes?” This is what one employee recalls Jeffries saying of a pair of corduroys intended for a “female” mannequin, in a moment that smacks of gay male misogyny at its worst. For Jeffries wanted women to look “ultra femme.” Adhere to some ideal of the eventual pearl-wearing mother that select gay men of a certain age do still so idolize.

What has never been idolized, even in the present, is most of the U.S. Which is why “tastemakers” controlling what shows up in stores have long deemed the parts of America between New York and L.A. as “flyover country.” However, during the era when A&F had so much clout, “flyover country” was suddenly looking like a delicious little cash cow because, as Klayman establishes through her subjects, the brand was able to sell what they said was trending through what people of the Midwest and the Bible Belt were seeing in magazines and on MTV (because, as we’re reminded, “Social media just wasn’t there” to manipulate otherwise).

And what they were seeing was Abercrombie. Worn by an array of 00s icons ranging from Lindsay Lohan to Britney Spears. It was, indeed, the former who served as a model for A&F before she really “blew up” in the wake of The Parent Trap. Having previously modeled for Calvin Klein (the primary inspiration Jeffries took for his hyper-sexualized marketing angle), Lohan fit the bill for what Jeffries viewed as “all-American.” Incidentally, Lana Del Rey, then Lizzy Grant, also adhered to that “look,” appearing in one of the campaigns with Lohan. In this regard, there’s something eerily apropos about Del Rey not only founding a career on “classic Americana” imagery, but also embracing the term “white hot.” Nearly calling one of her albums White Hot Forever before it became the more “dystopian prep” name of Chemtrails Over the Country Club (though she did incorporate, “We’ll be white-hot forever” into the lyrics of “Tulsa Jesus Freak”).

Then there was Taylor Swift, once fetishized by neo-Nazis as the ultimate Aryan ideal. She, too, would fall prey to the lure of becoming an Abercrombie model in 2003. For obvious reasons, a girl like her would be the “gold standard” for Abercrombie’s advertising. A gold standard that, as Robin Givhan, a senior critic-at-large for The Washington Post, states in the film, was designed to be “just ‘aspirational’ enough, but not so expensive that it was out of reach.” For those middle-class suburban kids who couldn’t afford Calvin Klein or Ralph Lauren, Abercrombie still seemed “elite” because someone who looked like Swift was modeling the clothes. Funnily enough, Abercrombie would, ten years after the Tay campaign, be forced to pull a slut-shaming tee with the “clever quip,” “More boyfriends than T.S.”

Another commentator only too happy to condemn the “selective” tactics of Abercrombie is journalist Moe Tkacik, who remarks, “I remember walking in [the first time] and just being hit with the sense of, like, ‘Oh my god, they’ve bottled this. They have absolutely crystallized everything that I hate about high school and put it in a store.’” Indeed, Abercrombie thrived on the psychology of “othering.” Establishing a very “us v. them” vibe between those who were “cool” (read: vanilla and preppy) and those who were not (anyone who didn’t want to adhere to this decidedly white-bread fashion).

Klayman then delves into how it all started. Because even before Jeffries came along to solidify the brand’s white supremacist aura, it already had that element built in from the get-go. It’s evolution as a brand for “real men” was a natural progression from being founded by two very white dudes in 1892 (as all of Abercrombie’s shirts like to tout) as an “upscale sporting goods” store patronized by the likes of “outdoorsmen” Teddy Roosevelt and Ernest Hemingway.

As the brand faltered into oblivion by the 70s and 80s, Leslie Wexner, the “Merlin of the Mall” and, later, known Jeffrey Epstein enabler, would pass the corporation off to Jeffries, at the time a “failed CEO” of Alcott & Andrews, a brand “that focused on professional businesswomen apparel” (try not to picture Romy and Michele in their matching black skirt suits asking if there’s some kind of businesswoman’s lunch special).

From his takeover as president in 1992, Jeffries emphasized the brand’s focus on the “youth market.” Specifically, the “all-American” teen. This escalated quickly as the company and those who worked for it became almost cultish in their fervor for all things A&F. One key “player,” David Leino, even tattooed the word “Abercrombie” on himself, a mark of how brainwash-y the company was. That the expectation was to live and breathe the lifestyle, lest you cease to fully buy into it at any given moment as one of the employees. Thus, A&F was able to treat itself as the fraternity/sorority it wanted to be. The place that every “aspirant of cool” should want to rush and be a part of.

And, once again, being that gay men were still regarded as pariahs or parodies at this moment in history, it seems more than absurd that, to market this ideal, A&F should choose Bruce Weber as the driver of the aesthetic the brand would become notorious for. Journalist Benoit Denizet-Lewis (who wrote the eventually viral article, “The Man Behind Abercrombie & Fitch”) says it plainly enough in the film with, “It was clear, to anyone who was paying attention, that there were many gay men involved in all of it.” Jeffries himself being repressed in his 1950s SoCal youth spent wearing Levi’s as his own way to “fit in,” maybe he only felt he could be out by being “subtle” about it (telling Denizet-Lewis in not at all coded language, “‘I broke my dad’s heart because I wasn’t good at basketball.’ In high school in the late 1950s, Jeffries always wore Levi’s jeans. ‘Actually, don’t write that,’ he tells me, laughing. ‘But Levi’s was definitely the uniform back then, kind of like what A&F has become. If you didn’t wear 501s you were considered weird’”—and so stemmed the diabolical origin story of why Jeffries became obsessed with peddling Normal).

Yet it was all meant to be “hyper-hetero”—which, of course, usually always tends to be a big cover-up for gayness. But more than heterosexuality, it was whiteness that A&F wanted to shill. Phil Yu, of Angry Asian Man, enters the conversation once the documentary starts to address Abercrombie’s many problematic graphic tees, a large portion devoted to harmful Asian stereotypes. Including the illustrious Wong Brothers Laundry Service shirt with the tagline, “Two Wongs can make it white.” The protests that ensued would only be a small taste of the backlash that was to befall A&F.

Then there was the class action lawsuit from several employees (Anthony Ocampo, Jennifer Liu and Carla Barrientos among the plaintiffs also featured in the movie) flagrantly discriminated against for not “looking Abercrombie enough,” a “polite” code for: not white. After the lawsuit, Abercrombie engaged in some “tokenism hiring.” A Black or Asian person here and there. They even went through the trouble of hiring a Black man as their “Chief Diversity Officer.” Somehow though, Todd Corley, who appears as an interviewee, comes across as being perhaps even more in denial about A&F’s white supremacy than Jeffries.

It took Samantha Elauf, a woman denied employment for wearing a hijab, to perhaps really make A&F see that it was, in a word, gross. The case was taken all the way to the Supreme Court in the form of Equal Employment Opportunity Commission v. Abercrombie & Fitch Stores. Determined in Elauf’s favor due to Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, it was clear to anyone (read: whites) who had doubts before that still “being on the side” of A&F was essentially like being on the side of Hitler Youth.

Like the Aryan-exalting Nazis, A&F saw an opportunity to mold and manipulate the minds that “wanted to be,” subsequently taking egregious liberties with their designs and marketing because they were allowed to for so long. Enabled by the then-dominant marketing system in place: TV and print magazines. One person in the documentary makes the time period of its reign sound even more like the Dark Ages because there was no social media for people to actively and regularly voice their outrage over what A&F was blatantly doing: othering. And that’s what the millennial experience was—constantly worrying about being “normal” and “accepted.” Not for who they actually were, but what the brands they wore were meant to project. Especially for those living in the suburban sprawls where A&F thrived who didn’t fit into the mold the brand forged. These were the kids even more likely to sport the clothing as a means to “fit.” Or at least blend into solid-hued oblivion.

It seems germane to bring up the aforementioned Senior Year in this regard, too. For, at one point, Stephanie, the millennial trying to navigate a newly Gen Z world, declares, “I’m gonna do something I wish I had the confidence to do twenty years ago: be my real self.” Because with Abercrombie casting such a large shadow over millennial life, it was practically impossible to be one’s “real self” for said generation forced to drink the marketing Kool-Aid. Just one of many ways in which Gen Z has diverged very overtly from their predecessors, possessing a near-obsession with “authenticity” despite that aim being impossible to achieve on any form of social media, least of all TikTok.

As the documentary comes to a close, Givhan hands Klayman her title on a silver platter by asserting, “You don’t want your brand to run white-hot. Because white-hot brands always burn out.” Other reasons for the brand’s “demise” (in spite of still existing) being that: “Exclusion itself stopped being cool.” Of course, that’s not really true. People are still inherently attracted to things that seem “exclusive.” Even cultures can come across as “exclusive” or “status-y,” after all. Including Black culture, which is currently fetishized to an overtly offensive degree by people like the Kardashians (Kim being mentioned at one point in the documentary by some outraged girl in a video circa 2013—when Kim was starting to really peak with cultural relevancy—as a person that A&F should “make room” for… a reference to their size-ist clothing styles).

Like Karl Lagerfeld openly fat-shaming and giving his own frequent deux centimes on a “classic” standard of beauty, Jeffries famously said in the Salon article that would ultimately seal his end as A&F’s CEO, “Candidly, we go after the cool kids. We go after the attractive all-American kid with a great attitude and a lot of friends. A lot of people don’t belong [in our clothes], and they can’t belong. Are we exclusionary? Absolutely. Those companies that are in trouble are trying to target everybody: young, old, fat, skinny. But then you become totally vanilla. You don’t alienate anybody, but you don’t excite anybody, either.” That, obviously, seems more than slightly laughable when taking into account that A&F is the very epitome of vanilla.

A&F might have been “worse” than most companies experiencing a “moment,” but, in the end, even in the face of their major rebranding post-Jeffries, Yu puts it best when he asks, “Can you really sell diversity inclusion when really what you’re trying to sell is a V-neck?” The overarching issue at the core of everything being that capitalism itself is set up to forever encourage exclusion in some form or another by making people “aspire” to want to buy certain products in order to appear a certain way. So, sure, the battle against A&F and its once-heralded image is “won.” But the war will rage on until this planet bursts into flames. And P.S. How Gen Z gonna criticize when they “heart” Shein?