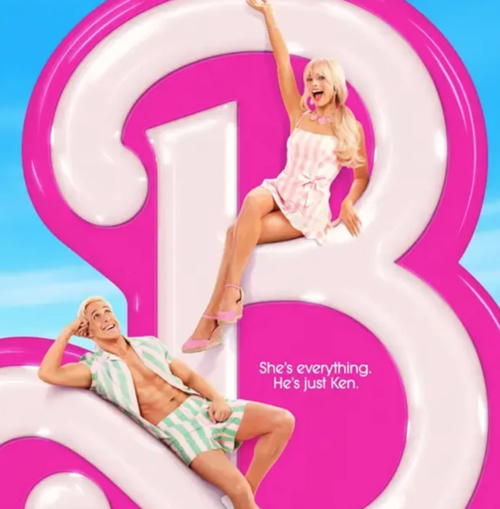

Of all the things about the latest round of the Barbie marketing blitzkrieg, perhaps the most standout element to the (feminine) masses was the tagline touting, “She’s everything. He’s just Ken.” This with Barbie (Margot Robbie) presented in the top “hole” of the B and Ken (Ryan Gosling) rightly situated “on bottom.” With five simple words, Greta Gerwig and Noah Baumbach (the Joan Didion [a fellow Sacramentan like Gerwig] and John Gregory Dunne of our time) have cut to the core of flipping the script on a societal viewpoint that’s typically directed at men…who see women as “background.” So often foolishly believing they’re the “stars” of the show with “old chestnuts” like, “Behind every great man is a great woman.” This horrific back-handed “compliment” of a saying serving only to reiterate that women’s reproductive and emotional labor is not only meant to be “invisible,” but it’s also expected. Simply “goes with the territory” of being a woman.

With the advent of the so-called Equal Pay Act in 1963 (just in the U.S., mind you), women were essentially told, “You can be ‘equal’ to men in the productive labor sphere, too—so long as you keep performing the same reproductive labor at home.” For to be a woman is to take on the burden of everything silently and with a smile. Perhaps that’s why it’s no coincidence that, just a few years earlier, Barbie’s creator, Ruth Handler, was incited to create a different kind of doll after witnessing her daughter play with the available toys for girls at the time, compared to those available for boys. The idea behind Barbie (named in honor of Ruth’s daughter, Barbara) thus arose from wanting to give girls the opportunity to envision their futures through lenses beyond just “mother” or “homemaker.”

Barbie was the first doll of its kind, encouraging women to imagine the possibilities of their gender beyond the clearly-defined role of “supporting act” to the presumed man in her life. As such, a year before the Equal Pay Act, Mattel released Barbie’s first Dreamhouse—the assumption being that she actually might have paid for it herself (Ken had only entered the picture a year before, in 1961)…even if this was still before a woman was “allowed” to open her own bank account. Chillin’ at the crib by herself, Barbie served as a catalyst for the idea that a woman could actually buy a home of her own one day, without the presence of a man to sully it. Or, if he did, at least she could tell him to get the fuck out.

Barbie’s undercutting feminist revolution continued in 1965, with the release of Astronaut Barbie, effectively proving that she, a woman, made it to the moon four years before Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong. Then, Mattel (with Ruth at the Barbie helm) got really progressive in 1968 by “daring” to introduce Christie, the first Black doll, and a purported friend of Barbie’s…which would technically make her an OG of allyship (apart from Marilyn Monroe), but let’s not make this any more about white women than it always is. Another major overhaul on the potential for what a woman “could” be occurred in 1985, with CEO Barbie (a true testament to the total embracement of capitalism-on-steroids under Reagan). The first of her kind to really show that a woman was able to “have it all.” But, again, the unspoken caveat here is that she’s still expected to carry out her “inherent duties” as a woman. This pertaining to the reproductive labor associated with household management and childcare.

In Alva Gotby’s They Call It Love: The Politics of Emotional Life, she gets to the heart of this double standard by noting, “Women’s labor, especially that which is sexual or maternal, is conflated with their bodies and constructed as a natural instinct. This naturalization is essential for the capitalist use of reproductive labor. The capacity for reproductive labor is turned into a natural quality of certain bodies whose function is primarily to carry out that labor. If it is not work, it is worthless economically, but also natural and therefore good.” This is part of the reason Barbie’s various “personae” have been fractured into so many “professions,” all while still maintaining her plastered-on smile and ostensibly “personable” aura (read: looking like the classic male ideal of what a female should “be”). All of which is expected of a “good” woman. “The naturalization of feminized labor, and particularly emotional labor,” Gotby adds, “not only makes that work appear as unskilled labor but also makes it invisible as labor. It is merely an eternal and unchangeable quality of feminine personalities… Women’s emotional labor is seen as a natural expression of their spontaneous feeling, something that is in turn used to further exploit this work.” I.e., touting that women “can have it all” while Ken sits back and actually does fuck-all.

Hence, “He’s just Ken.” He gets a gold star just for being there. Whereas women have to work twice as hard in every facet of life to be taken “seriously.” Which is where the matter of women’s appearance comes into play. On the one hand, if a woman is “hot,” like Barbie, the snap judgment that will be made about her is that she must not be very smart. On the flipside, a woman won’t be considered for much of anything at all if she doesn’t put some “effort” into cultivating a “pleasant” appearance. Barbie reinforces this trope for sure. She’s “visually pleasing,” but she can also embody everything from eye doctor Barbie to smoothie bar worker Barbie, transitioning from white to blue collar work as effortlessly as Pete Davidson transitions from one high-profile girlfriend to another.

So yes, “She’s everything. He’s just Ken” has never felt more resonant as a much-needed spotlight on the continued manner in which women are expected to be literally everything (particularly a hybrid of mother/girlfriend) to everyone while men can just show up without putting in any of the excess emotional labor that women have to. They’re just men, after all. Only so much can be expected of “God’s gift.”

[…] Genna Rivieccio Source link […]