As Winona Ryder, who turns forty-seven on October 29th (in typical goth Lydia Deetz fashion because of that Scorpio/near Halloween cachet), once explained of her loneliness and depression to Diane Sawyer on 20/20 back in 1999, “I saw myself on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine, and it said, something like, ‘Winona Ryder: The Luckiest Girl in the World.’ And…it broke my heart because there I was, you know, in so much pain and feeling so confused, feeling so lost in my life. Um, I wasn’t allowed to complain because I was ‘so lucky,’ you know, and I was ‘so blessed’ and I made a lot of money and, you know, my problems weren’t real problems, and I mean, I’m as nauseated as the next person when actors complain about their lives. You know, we are blessed, we are lucky. But the stuff that I was going through was difficult.”

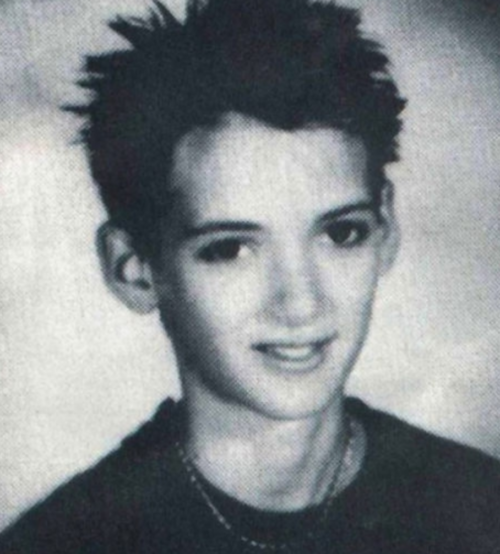

It was that “stuff” that Winona Horowitz was forced to endure early on in preadolescence, when she was bold and courageous enough to commit to her androgynous aesthetic in a part of the U.S. as narrow-minded as Northern California (which, no, does not mirror the “liberal” “babe-aliciousness” of a setting like Los Angeles). A survivor of Kenilworth Junior High in Petaluma (her parents moved her there when she was ten), Ryder recalled of one of her earliest traumas for being “different,” “I was wearing an old Salvation Army shop boy’s suit. As I went to the bathroom I heard people saying, ‘Hey, faggot.’ They slammed my head into a locker. I fell to the ground and they started to kick the shit out of me. I had to have stitches. The school kicked me out, not the bullies. Years later, I went to a coffee shop and I ran into one of the girls who’d kicked me, and she said, ‘Winona, Winona, can I have your autograph?’ And I said, ‘Do you remember me? Remember in seventh grade you beat up that kid?’ And she said, ‘Kind of.’ And I said, ‘That was me. Go fuck yourself.'”

But it wasn’t as satisfying as Veronica Sawyer eradicating school bullying altogether in Heathers with the haughty line, “Heather, my love, there’s a new sheriff in town.” Still, one would think that vindication was Ryder’s in 1988, when already at the age of sixteen, she had achieved her first major box office success with the number one movie in the country for four weeks in a row, Beetlejuice. Perhaps only Christina Aguilera years later (with the scene that unfolded when “Genie In A Bottle” played at her prom and everyone cleared the dance floor in protest) would understand that rather than peers bowing down to such success in high school, they instead prefer to tear you down and make you feel like complete and toto shit for shining your light, the one that they don’t have, and never will. Because in order to have the light you must be close enough to the sun, and have your head in the clouds as a result. Which is, accordingly, why so many are always trying to pull you back down to earth. As they did with Winona and her assured sense of self. Assured, that is, until she had the light beat out of her. In its place, a darkness radiated. A vulnerable one–the one we see emanating from Lydia Deetz, Veronica Sawyer, Charlotte Flax, Roxy Carmichael, Lelaina Pierce, Finn Dodd and Susanna Kaysen. But it is a very specific light-tinged darkness. The kind that can only come from suffering early on for being classified as “peculiar,” “eccentric” or otherwise “grotesque” because you don’t fit into some preconceived mold that makes it easier for everyone to swallow. And isn’t life, evidently, all about making things “palatable” for others who are, in fact, quite dull? In turn, for whatever reason, wanting to render everyone else around them equally as so by stamping out their will to be themselves.

Fortunately, Tim Burton, white male that he is, was somehow given license to eke through the Hollywood system so as to bring everyone a taste of what would later, oh so ironically, be mass marketable: weird. But “cute weird.” Manic pixie dream girl weird. And yes, Winona Ryder helmed that concept long before Nathan Rabin, except she was not “playing that character” for the sake of serving up some sort of stock (false) growth for a male protagonist. Ryder’s roles always came from a genuine place of pain and torment, hence the sensitivity evident in each of them, of the variety that comes but once in a generation of actors. And even in her “bitch” roles (e.g. Nicola Anders in S1m0ne, Melissa Warburton on Friends or Beth Macintyre in Black Swan), she is able to effectively convey the antagonism from the brutal place that she endured it firsthand from the perspective of the antagonized.

The culmination of this emotional nakedness manifested most succinctly in Girl, Interrupted, which Ryder herself executive produced. As the protagonist (with the show more than occasionally stolen by sociopath Lisa [Angelina Jolie]), Ryder imbues Susanna with the fragility that so many of us feel on a day to day basis as a sheer result of leaving the house and interacting with the predictably harsh environs and people outside. So it is that both Susanna and Winona (at one point in the 90s) check themselves into a psych ward, only to realize that “crazy isn’t being broken, or swallowing a dark secret. It’s you, or me, amplified. If you ever told a lie, and enjoyed it. If you ever wished you could be a child, forever.” And on the screen, Winona is just that, forever–regardless of how many birthdays pass. It is at her very core at every phase of life, that childlike innocence and angst that can only stem not from the toughness, but the delicacy that results from being tormented during a formative moment in your existence.