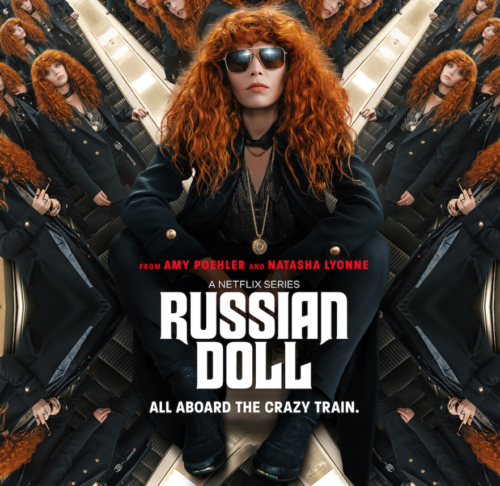

It was almost too prescient that a show about being stuck in a time loop should come out right before corona did. For Russian Doll’s first season arrived onto the scene in early 2019, just in time for Groundhog Day. Seeming to continue to have a sense of humor about dates, Russian Doll’s second season was unleashed on 4/20. Perhaps to ensure that anyone watching would be on drugs in order to wrap their heads around the mind-fuck regarding not just traveling back in time, but traveling back in time and into your mother. That’s what happens when you take the 6 train, apparently. Rather under the radar ever since J. Lo stopped mentioning it. But with Russian Doll to bring it back to the forefront of the pop cultural sphere, it’s entirely possible one will be seeing far more people taking the 6 from 77th Street to Astor Place in order to get back to the ultimate romanticized time in New York: the 80s.

That’s right, the last decade anyone in New York can remember truly being “enchanted” by it (“enchantment’ meaning getting an erection over how “grimy” and “real” the city used to be, even if it meant you couldn’t walk a few blocks without probably getting mugged). This was pre-Disney takeover New York. The “real deal”—before that term became associated with a real estate website. And yet, Nadia (Natasha Lyonne, almost purposefully putting on the most annoying New York accent possible) is not at all thrilled to be back in the decade of Ed Koch upon having the revelation that she is. Maybe it would help if she was still herself when she went back to the 80s, instead of suffering from that nesting doll syndrome of being stuck inside someone else—namely, her mother, Lenora (Chloë Sevigny, the requisite casting choice for any “indie” New York-based project).

As the slow revelation begins to dawn on her that she’s somehow “leveled up” on her time tampering abilities, she holds a newspaper (the first clue that this is no longer 2022) in her hands—with an ad for Tab on the back—that says, “The Two Faces of John LeBoutillier.” Elected as the Congressional representative of NY’s sixth district (Queens), he was fined by the Federal Election Commission in 1983 for taking donations from individuals above the accepted limit—including a $200,500 one from his own mother. Just another testament to political corruption in the New York of the 80s. As Nadia then looks at the year printed on the newspaper and mutters, “Nineteen…eighty-two,” she starts to look more closely at the subway ads as well, one of which offers “5 Ways to Not Get Mugged” as a “solution” for mitigating one’s fear on the subway. Ironically, of course, a sign such as that might just as easily appear in the climate of New York’s present. Plagued as it is with unhinged subway riders.

Coming to terms with the subway as a time travel machine, Nadia gets out at the Astor Place of ’82 with grudging acceptance as she unearths that, in place of where her phone was, is a matchbook with a logo for a bar called The Black Gumball on it. Complete with an inscription that reads, “See you at 8. Chez.” That’s short for Chezare (though it should be Cesare) Carrera (Sharlto Copley). A deadbeat lowlife who she quickly finds out is her mother’s boyfriend du jour.

As she walks into The Black Gumball, she hears a man saying, “Of course, American religion at its core has always been consumerism, but now, the illusion’s fading away and we’re left worshipping the thing itself. The pursuit of money for money’s sake.” The episode is filled with many such yuppie condemnations, considering it was the “beginning of the end” for an “artistic” New York. Even if the city was always about and a beacon of making money above all else.

“You’re a time traveler?” a fellow bar patron asks. Nadia ripostes, “I prefer the term ‘time prisoner.’” As the two briefly get to talking, with Nadia unveiling him as an employee (“Betamax Specialist”) at Crazy Eddie’s, it’s clear that she doesn’t seem to be doing much of her own work lately. Instead of being focused on software programming, she’s more focused, ostensibly, on Ruth’s (Elizabeth Ashley) withering health and the fact that she’s now about to turn one of the scariest ages of all (unless you’re Madonna): forty. Which, yes, means she broke out of the time loop we first saw her trapped in. But if season one was about breaking out of the loop, season two is about breaking time itself. And with the family lineage narrative at play throughout, Russian Doll starts to bear many parallels to another Netflix-backed show: Dark. Of course, it would seem unfathomable that any film or show about time travel could ever top the complex quagmire the creators of Dark were able to weave. But Russian Doll does its best in its role as “what America has to offer for intellectualism.” Which, unfortunately, remains New York. Proudly putting the “pseudo” in “pseudo-intellectual” for quite some time.

Lyonne, with her deadpan delivery and aura of wryness, accordingly shows us why Woody Allen had such a hard-on for casting her in Everyone Says I Love You. That, and her Semitic heritage, which is of key emphasis as the origin story of how her Hungarian grandmother, Vera (Irén Bordán), came to be so protective of Nadia’s birthright: a bag of Krugerrands. An inheritance that soon seems doomed to always fall out of the Vulvokovs’ hands.

But it takes Nadia a while to face this reality as she rushes out of the 80s with the heebie-jeebies, boarding the train again and asking, “Is it 2022 in here?” This being demanded as she gets on the subway numbered “6622.” Because one should know their subway’s make and serial number as part of what Nadia calls “Quantum Leaping 101.”

As is the case in “real life” chronological order, it’s been three birthdays since Nadia and Alan (Charlie Barnett) broke out of the time loop. Thus, when she goes to see him after her bizarre experience time traveling into her mother, the dialogue that ensues is a mirror of anyone’s conversation since the pandemic began. She asks, “Are you happy?” He shrugs, “Yeah, I’m fine. I just—I think this is what life feels like.” “Is it though?” she counters.

In the second episode, “Coney Island Baby,” she decides to go after Chez for being what she initially thinks is the source of her family’s lost fortune. Because, upon going back to the 80s again, she decides to investigate Chez in the present, finding a Bronx residence and bursting inside to lay it all on him. He insists he didn’t steal the gold, however, and then goes on to explain that Nadia is suffering from what his family calls the “Coney Island.” In other words, “It’s the thing that would’ve made everything better.” An expression stemming from his father going to Coney Island and catching polio, ending up in an iron lung and unable to work. Old Chez adds, “If only he hadn’t gone to Coney Island that summer, he wouldn’t have gotten the airborne polio.” But “Coney Island” is just that—an “if only.” And Chez is the first to plant the seed that we only think we can change the course of our fate if we had done “just one thing” differently.

But Nadia remains unconvinced of predestination and, seeing that Chez used to play squash at the Bowery Rec Center thanks to a framed photo in his apartment, she decides to go there in 1982, where Chez tells her—or rather, her mother—in the locker room, “You can’t be in here.” And it reminds one of the cop in Everything Everywhere All At Once saying the same thing to Jobu Tupaki (Stephanie Tsu). But of course, she can be. Transcending time and space to do just that. Be there. Again highlighting the limits of language when it comes to explaining things.

But one word that does explain certain things about why people are the way they are is “epigenetics.” Which Nadia explicitly brings up as being a phenomenon that goes against the nature vs. nurture theory, which is, as far as she’s concerned, a form of eugenics (founded by scientific racist Francis Galton). Epigentics, in contrast, is something she needs to believe in even more as she looks back on her lineage while actually living inside of it.

By the third episode, “Brain Drain,” inhabiting her mother’s body for too long appears to be producing some eerie effects, including the bugs that start coming out of her skin in places that look like the bodily ravages of a heroin addict. In a new trippy effect, Nora’s schizophrenia seems to help Nadia split from her body entirely and actually exist outside of her. Meanwhile, Alan, who initially came across as uninterested in the idea of traveling back in time through his ancestors, has clearly fallen down the rabbit hole in episode four, “Station to Station” (a nice lil’ Bowie nod). Inhabiting his grandmother’s body in the East Berlin of 1962, Alan proves sexuality is irrelevant in any husk as he finds himself attracted to Agnes’ (Carolyn Michelle Smith) love interest, Lenny (Sandor Funtek).

The implications of Alan’s fondness for him will not come to roost until he realizes Agnes drafted a plan for Lenny to crawl through a tunnel to West Berlin. But before he has his own inclination to intervene and stop Lenny from going through with the plan, he tells Nadia, “Literally every movie about time travel says don’t change things.” Which is part of why Alan is so content to “just exist” in the past without trying to alter its course. Until, that is, his emotions become involved. That, to be sure, is always the great risk with time travel operations, as Back to the Future elucidated.

Russian Doll does start to innovate a bit more than other offerings of the time travel genre in the penultimate episode, “Schrödinger’s Ruth,” wherein she, as her mother, ends up actually giving birth to herself. A nod to Schrödinger’s cat, the multiple Ruths (and Nadias) that show up in this narrative pay homage to Schrödinger’s thought experiment about quantum superposition. One in which the cat in question can be considered both dead and alive depending on a certain event that may or may not occur. In that sense, Ruth is both dead and alive as Nadia goes through her time travel gambit with her Baby Self in tow. A move that patently starts to cause time to collapse into itself, a product of the nefarious bootstrap paradox. So nefarious, in fact, that she and Alan end up back in her birthday party time loop. Nonetheless, Nadia remains convinced that she deserves a better parent than the mother she was saddled with and isn’t so willing to give up on “saving herself.”

That’s why, in the final episode, called “Matryoshka” (referring to a set of nesting dolls of decreasing size placed inside one another), she seethes, “Do you know who I could’ve been if everything had been different? If anything had been different? The chance to be the me I could’ve been literally slid out of my body on a 6 train platform.” And how many of us so often think of that when it comes to the birth lottery? Particularly for those who were not born to wealthy and/or famous parents? But then, it all goes back to what Chez said at the beginning: “It’s a Coney Island, right? The thing that would make everything better if only it had happened, right? Or it didn’t happen. You know, an ‘if only.’” Naturally, this feels like Lyonne’s own way of assuring us all that we don’t really have a choice in how things turn out. If your life was destined to be shit, it was destined to be shit.

We also get a total Truman Show moment in “Matryoshka,” when Alan and Nadia, at separate times, walk through the water of the subway station void (a kind of Sheol, if you will) and up the stairs through a doorway that leads back into so-called “reality.” As Nadia decides that she will surrender to Time and give herself back to her “rightful” mother, she sees a younger version of herself on the train reading a copy of Demian. And it seems to make her understand that, no matter how horrendous her upbringing, she would not be who she is without it. More time travel moralizing, bien sûr. Or: things we tell ourselves in order to be contented with The Way It Is.

On a side note, for those wondering why Rosie O’Donnell’s name is in the credits for every episode, it’s because she’s the voice of the subway announcer. Chosen for such a part “because we knew we wanted a real New York accent. We were sort of running down the line, we’re like, ‘Rosie Perez, Rosie… Mike Rapaport.’” Incidentally, and to play up New York’s incestuousness, Lyonne was kicked out of the apartment she was renting from her then-landlord Rapaport in 2005 due to “complaints about her behavior” from other tenants. Maybe the fact that Lyonne was willing to cast Rapaport says one thing about time: it makes people grow soft. Or maybe it says that, because she didn’t (instead opting for O’Donnell), time does anything but heal all wounds.